Blog

GPCRs: Bridging the Gap in the Druggable Genome

Nov 30, 2025

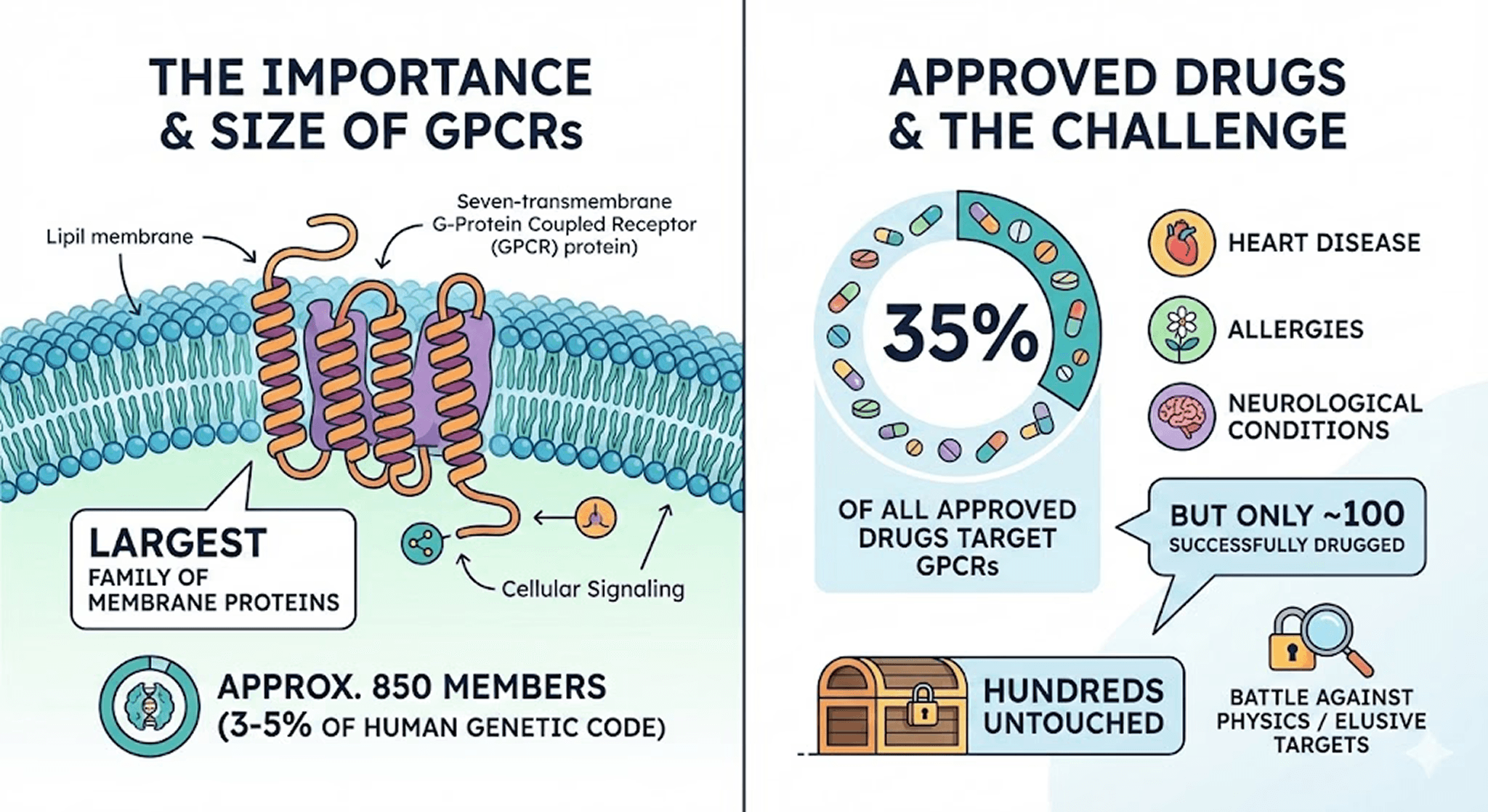

If you look at the human genome, you will find a family of proteins that works harder than almost any other. They are the G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs).

With around 850 members—making up 3-5% of our entire genetic code—they are the largest family of membrane proteins in humans. They are the targets for nearly 35% of all approved drugs, treating everything from allergies to heart disease.

But here is the fascinating puzzle that keeps structural biologists like me up at night: Despite their immense value, we have only successfully drugged about 100 of them.

This leaves 750 targets untouched. Why? It's not a lack of interest; it's a battle against physics. Let's dive into why these membrane proteins are so elusive and how new technology is finally helping us crack the code.

What Are G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)?

Think of a cell like a fortress. It needs to know what is happening outside without letting just anything inside. GPCRs are the "doorbells" or "inboxes" sitting on the fortress wall (the cell membrane).

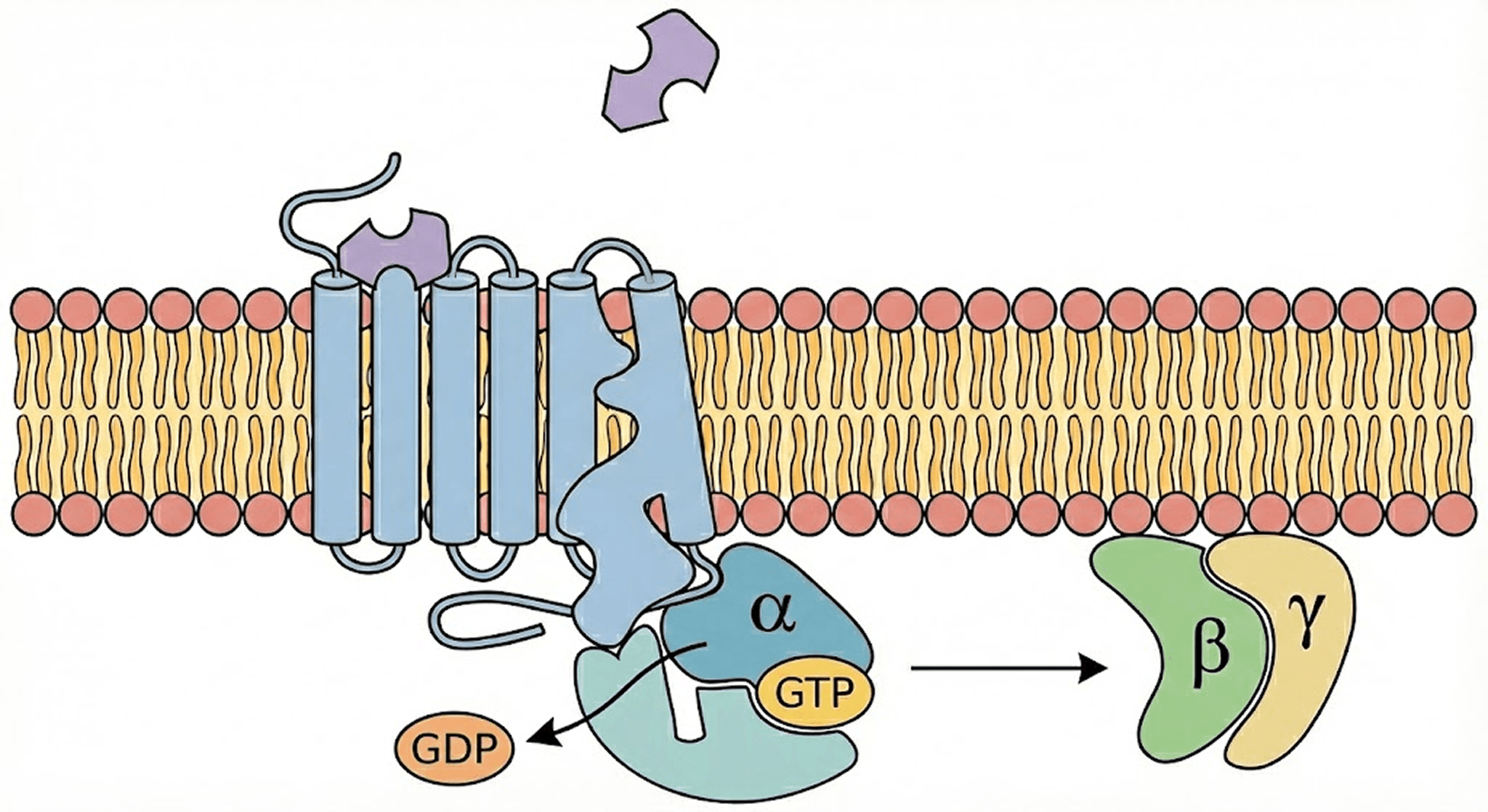

The process is elegant but complex:

The Signal: A specific molecule (ligand) floats by outside the cell and presses the doorbell—it binds to the GPCR.

The Shift: The GPCR changes its shape (conformation).

The Handoff: Inside the cell, a G-protein (attached to the receptor) feels this shift. It drops a molecule called GDP and grabs a high-energy GTP.

The Action: The G-protein splits apart. Its subunits G-alpha and the G-beta-gamma-dimer zoom off to interact with other proteins, triggering a cascade of signals that tells the cell what to do.

Case Study: Beta-2 Adrenergic Receptor Structure Determination

To understand why GPCR structure determination is so challenging, let's look at a celebrity of the protein world: the Beta-2 Adrenergic Receptor (β2-AR).

You interact with this receptor every time you get scared. It binds to adrenaline (epinephrine). When it activates, it tells your airways to open up and your heart to beat faster. It is also the specific target for Albuterol, the drug in asthma inhalers that saves lives during asthma attacks.

For decades, scientists knew this receptor existed, but nobody could see what it looked like. Nobel Laureate Brian Kobilka spent over 20 years trying to capture its structure. The problem? As soon as he extracted it from the cell membrane, it flopped around or fell apart. It was too "moody" to sit still for a picture.

It wasn't until he used clever protein engineering—literally cutting off a "floppy" part of the receptor and replacing it with a stable protein from bacteria (T4 lysozyme fusion)—that he could finally freeze it in place. This struggle illustrates exactly why the "undrugged" GPCRs are still waiting for their moment.

Why Are GPCRs So Hard to Study? The Three Major Challenges

As the β2-AR story shows, the main issue is the biophysical properties of these membrane proteins.

1. Membrane Protein Instability: The Shapeshifter Problem

To design a drug, we usually need a static "picture" of the protein's structure so we can build a molecule that fits it perfectly. However, GPCRs are extremely flexible. They constantly vibrate and shift between conformational states (inactive, intermediate, and active).

Furthermore, because they live inside the oily lipid bilayer, they hate being taken out. If you try to study them in a standard aqueous solution, they often denature and aggregate. This makes both X-ray crystallography and even modern Cryo-EM challenging.

2. Orphan GPCRs: Unknown Ligands, Unknown Functions

For a GPCR to hold still long enough for us to determine its structure, we usually need to bind a ligand to it—this stabilizes a specific conformation. But for many GPCRs, we have no idea what their natural ligand is.

These are called Orphan GPCRs, and they represent a significant portion of the undrugged targets. Without a molecular key to lock them in place, they remain structurally elusive. Even worse, without knowing what activates them, we don't fully understand their biological function or therapeutic potential.

3. Lipid Bilayer Dependency: Context Matters

You cannot simply study the protein in isolation; you have to study the protein in its native membrane environment. GPCRs have intracellular and extracellular loops that interact with the lipid bilayer in complex ways.

Specific lipids (like cholesterol and phosphatidylinositides) can modulate GPCR activity and stability. Removing the protein from this context often destroys its native structure. This is why techniques like nanodisc reconstitution and lipid cubic phase crystallization have become essential tools.

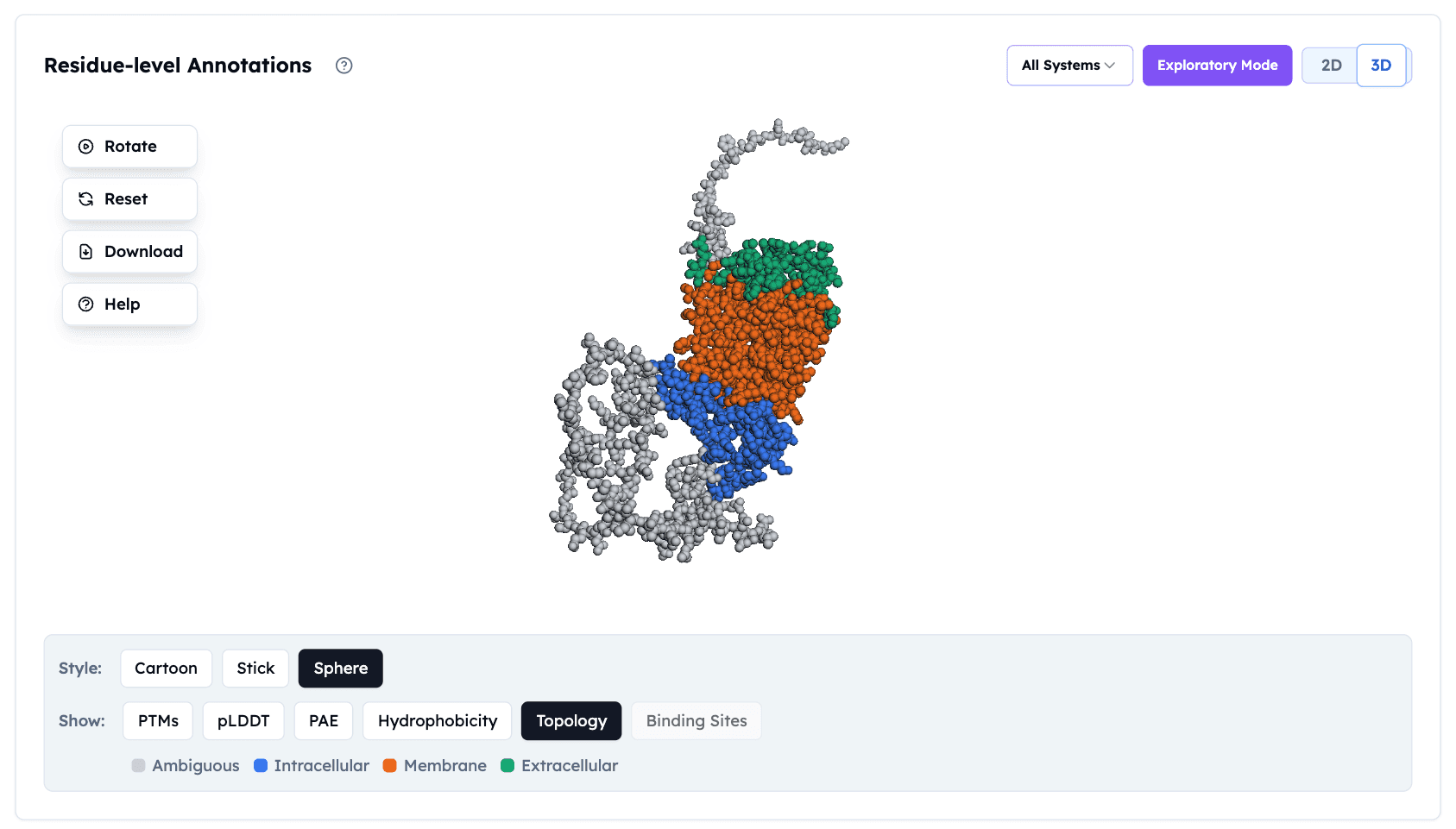

GPCR topology visualization in the Orbion platform, showing membrane-spanning regions (orange), intracellular loops (blue), and extracellular domains (green). This residue-level annotation helps identify optimal sites for stabilizing mutations.

How Modern Technology Is Solving the GPCR Problem

Fortunately, the last 20 years have brought a technological revolution. We are no longer shooting in the dark. Here are the four tools changing the game:

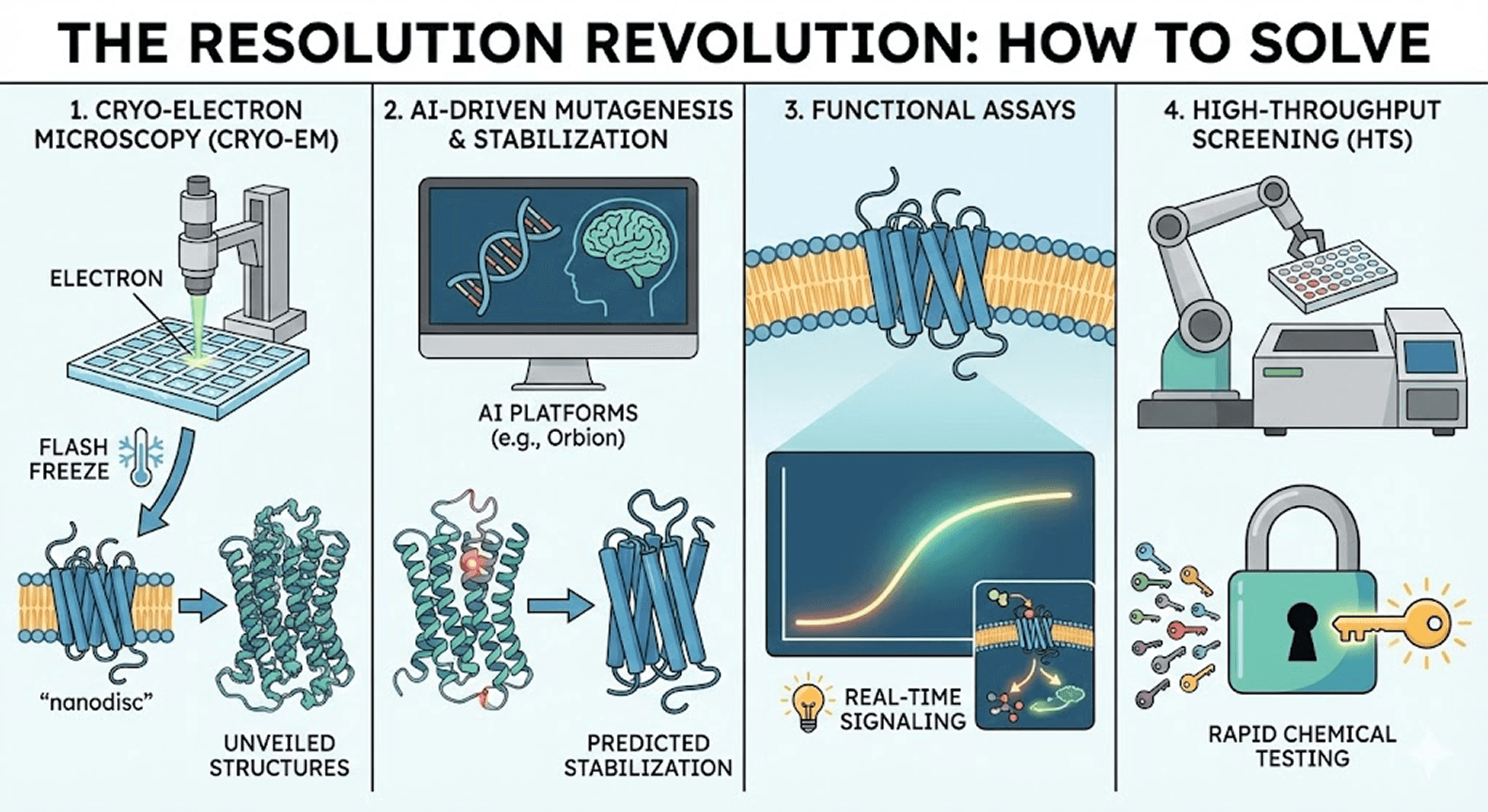

1. Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Seeing Proteins in Their Natural State

For decades, X-ray crystallography was the gold standard, but it struggled with flexible membrane proteins that refused to crystallize. Enter Cryo-EM.

This technique allows us to flash-freeze proteins in their natural state—sometimes even within a patch of membrane (nanodiscs)—and image them directly using electron beams. Unlike crystallography, Cryo-EM doesn't require a perfect crystal, making it ideal for GPCRs.

The impact: Cryo-EM has unveiled the structures of dozens of GPCRs that we previously thought were impossible to visualize, often at near-atomic resolution (2-3 Ångströms).

2. AI-Driven Mutagenesis & Stabilization: From Months to Days

This is one of the most exciting frontiers in structural biology. To keep a GPCR stable outside the cell, we often introduce tiny changes to its DNA—point mutations—to make it stiffer without breaking its function.

Historically, this was trial and error—testing hundreds of mutations in the lab over months or years. Today, we use rational design and AI platforms (like Orbion) to predict exactly which mutations will stabilize the receptor.

The result: What used to take 6-12 months of experimental screening can now be done computationally in days. This dramatically accelerates the path from target identification to structure determination, allowing us to produce milligram quantities of stable protein for structural studies.

3. Functional Assays: Beyond Static Structures

We are moving beyond just looking at structure. New bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) and fluorescence-based technologies allow us to light up the signaling pathway in real-time within living cells.

This helps us see if a drug candidate isn't just binding, but actually modulating the biological activity we want—whether it's an agonist (activating the receptor) or antagonist (blocking it).

4. High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Testing Millions of Molecules

Since we can't always predict the perfect drug computationally, sometimes we play the numbers game. HTS platforms allow robots to test millions of chemical compounds against a GPCR in parallel.

Modern HTS can screen 100,000+ compounds per day. It's like trying a million keys in a lock at once to see which one turns. Combined with AI-guided compound library design, this approach has identified novel scaffolds for previously "undruggable" targets.

A Golden Age for GPCR Drug Discovery

GPCRs are challenging, yes. They are unstable, finicky, and complex. But they are also the gatekeepers to treating some of the world's most difficult diseases—from chronic pain and neurological disorders to metabolic diseases and cancer.

The numbers tell the story:

750 undrugged GPCRs represent billions of dollars in therapeutic potential.

Orphan GPCRs may hold the key to currently "undruggable" diseases.

Improved structural techniques are accelerating discovery timelines by 10×.

With the convergence of AI-driven protein engineering, Cryo-EM, and smarter stabilization techniques, we are entering a golden age of structural biology. The "undruggable" targets are finally coming within reach.