Blog

The Batch-to-Batch Variability Problem in Protein Production

Feb 11, 2026

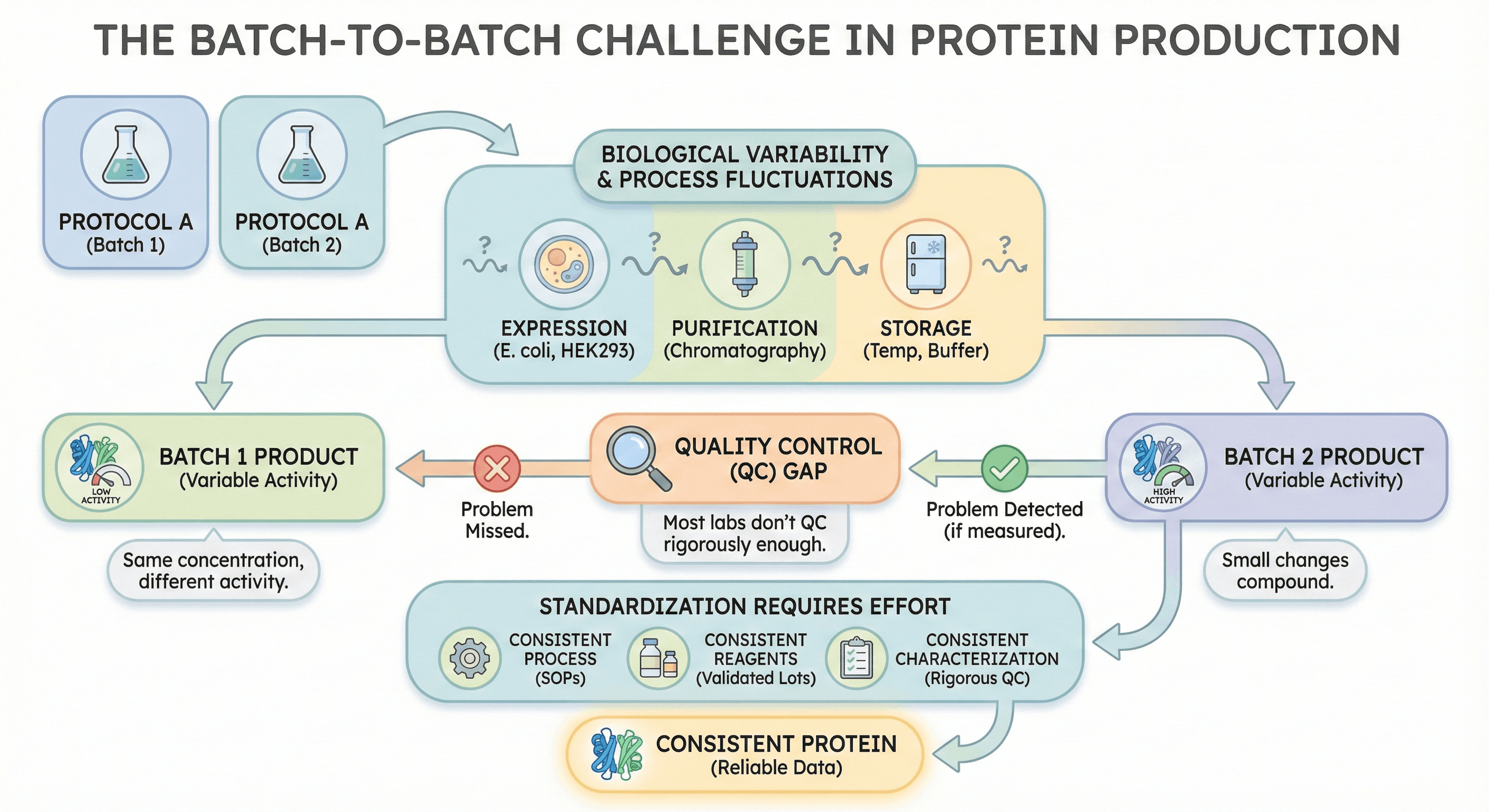

Last month's protein worked perfectly. Same construct, same protocol, same everything. This month's batch has half the activity, runs as multiple bands on the gel, and aggregates during concentration. You've changed nothing—but the results changed anyway.

Welcome to batch-to-batch variability, the silent killer of reproducibility in protein biochemistry.

Key Takeaways

Identical protocols don't guarantee identical products: Biological production systems have inherent variability

Small changes compound: Minor fluctuations in expression, purification, and storage accumulate into major differences

Activity variation matters more than concentration: A batch with the same protein concentration can have vastly different specific activity

Quality control catches problems only if you measure: Most labs don't QC rigorously enough to detect batch differences

Standardization requires effort: Consistent protein requires consistent processes, reagents, and characterization

The Hidden Variability Problem

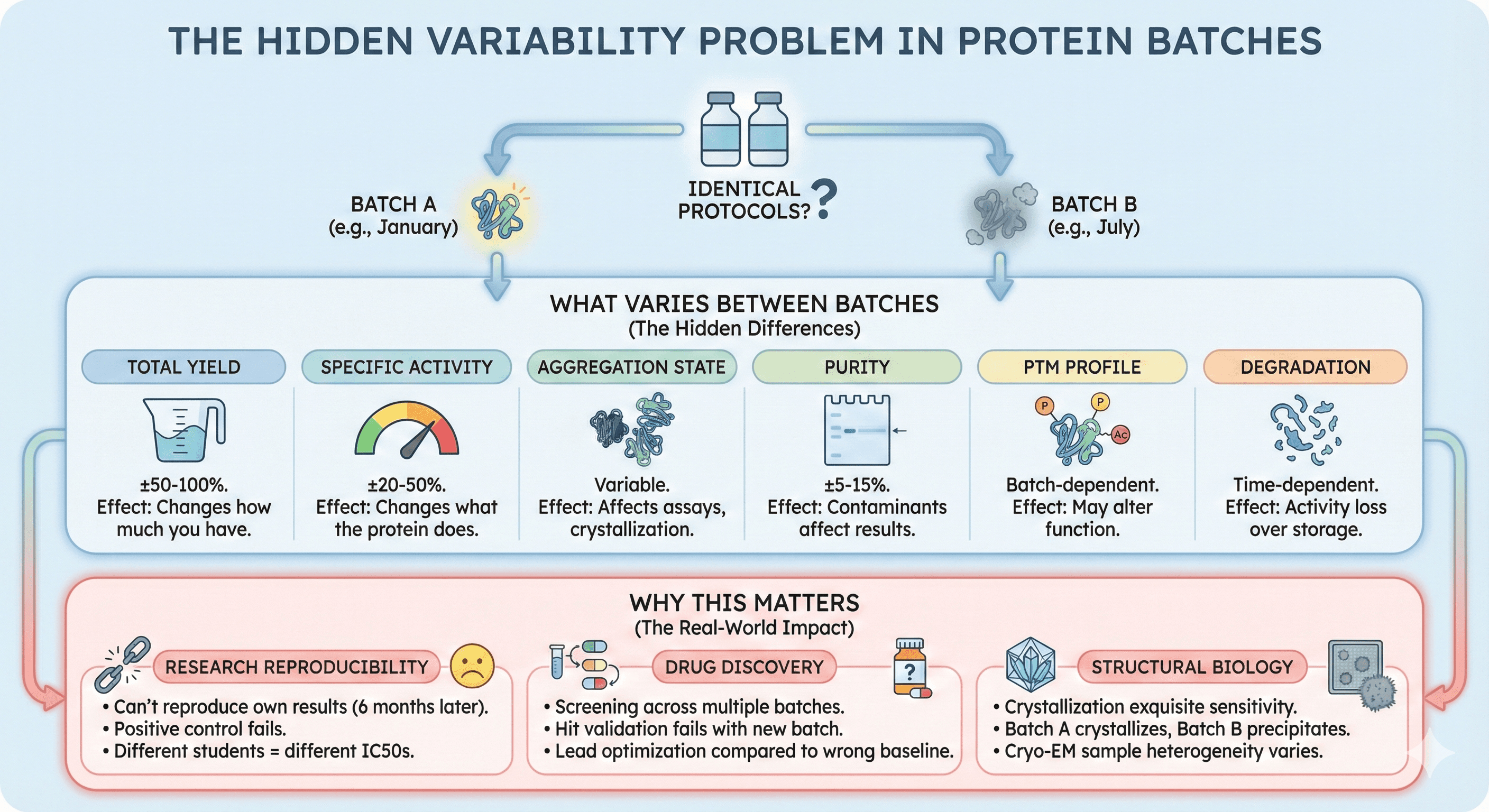

What Varies Between Batches

Even with "identical" protocols, each protein batch differs in:

Property | Typical Variation | Downstream Effect |

|---|---|---|

Total yield | ±50-100% | Changes how much you have |

Specific activity | ±20-50% | Changes what the protein does |

Aggregation state | Variable | Affects assays, crystallization |

Purity | ±5-15% | Contaminants affect results |

PTM profile | Batch-dependent | May alter function |

Degradation | Time-dependent | Activity loss over storage |

Why This Matters

Research reproducibility:

"We can't reproduce our own results from six months ago"

"The positive control doesn't work anymore"

"Different students get different IC50 values"

Drug discovery:

Screening campaigns span multiple protein batches

Hit validation uses different batch than primary screen

Lead optimization compared to wrong baseline

Structural biology:

Crystallization conditions are exquisitely sensitive to protein quality

Batch A crystallizes, Batch B doesn't—same conditions

Cryo-EM sample heterogeneity varies with batch

Sources of Variability

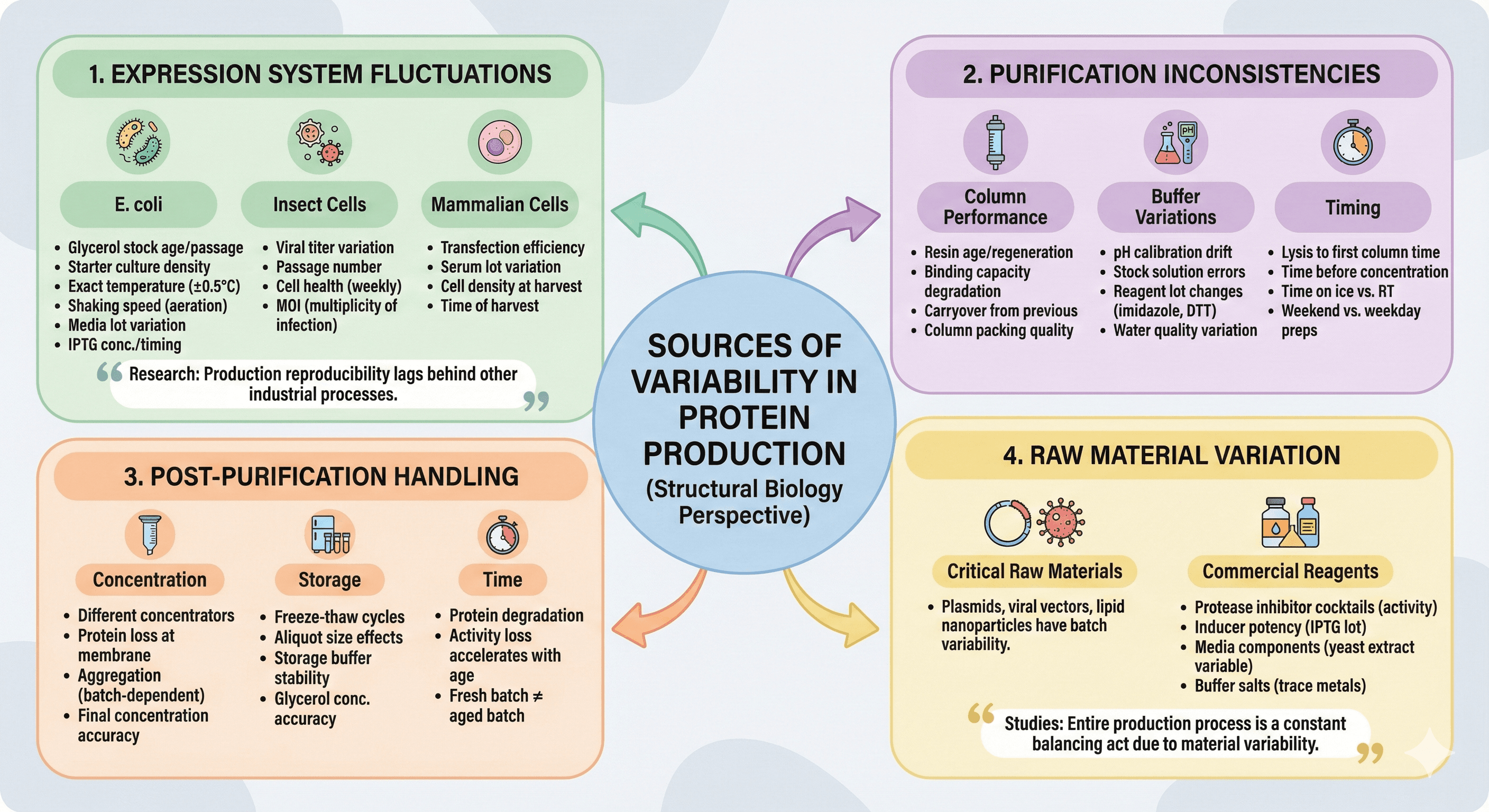

Source 1: Expression System Fluctuations

E. coli:

Glycerol stock age and passage number

Starter culture density at induction

Exact temperature (even ±0.5°C matters)

Shaking speed affects aeration

Media lot-to-lot variation

IPTG concentration and timing

Insect cells:

Viral titer variation

Passage number affects expression

Cell health varies week to week

MOI (multiplicity of infection) critical

Mammalian cells:

Transfection efficiency varies

Serum lot variation (if used)

Cell density at harvest

Time of harvest after transfection

Research on fed-batch cultures has shown that "with respect to batch-to-batch reproducibility, production processes for recombinant proteins are lagging far behind most other industrial processes."

Source 2: Purification Inconsistencies

Column performance:

Resin age and regeneration history

Binding capacity degrades over time

Carryover from previous purifications

Column packing quality

Buffer variations:

pH meter calibration drift

Stock solution concentration errors

Reagent lot changes (imidazole, DTT, etc.)

Water quality variation

Timing:

Time between lysis and first column

How long protein sits before concentration

Time on ice vs. at room temperature

Weekend preps vs. weekday preps

Source 3: Post-Purification Handling

Concentration:

Different concentrators have different characteristics

Protein loss at membrane varies

Aggregation during concentration is batch-dependent

Final concentration accuracy

Storage:

Freeze-thaw cycles

Aliquot size affects freeze-thaw damage

Storage buffer stability over time

Glycerol concentration accuracy

Time:

Protein degradation is time-dependent

Activity loss accelerates with age

Fresh batch ≠ aged batch

Source 4: Raw Material Variation

Studies emphasize that "critical raw materials such as plasmids, viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles, etc. also have batch-to-batch variability, which means the entire production process is a constant balancing act."

Even commercial reagents vary:

Protease inhibitor cocktails (activity varies)

Inducer potency (IPTG lot variation)

Media components (yeast extract is notoriously variable)

Buffer salts (trace metal contamination)

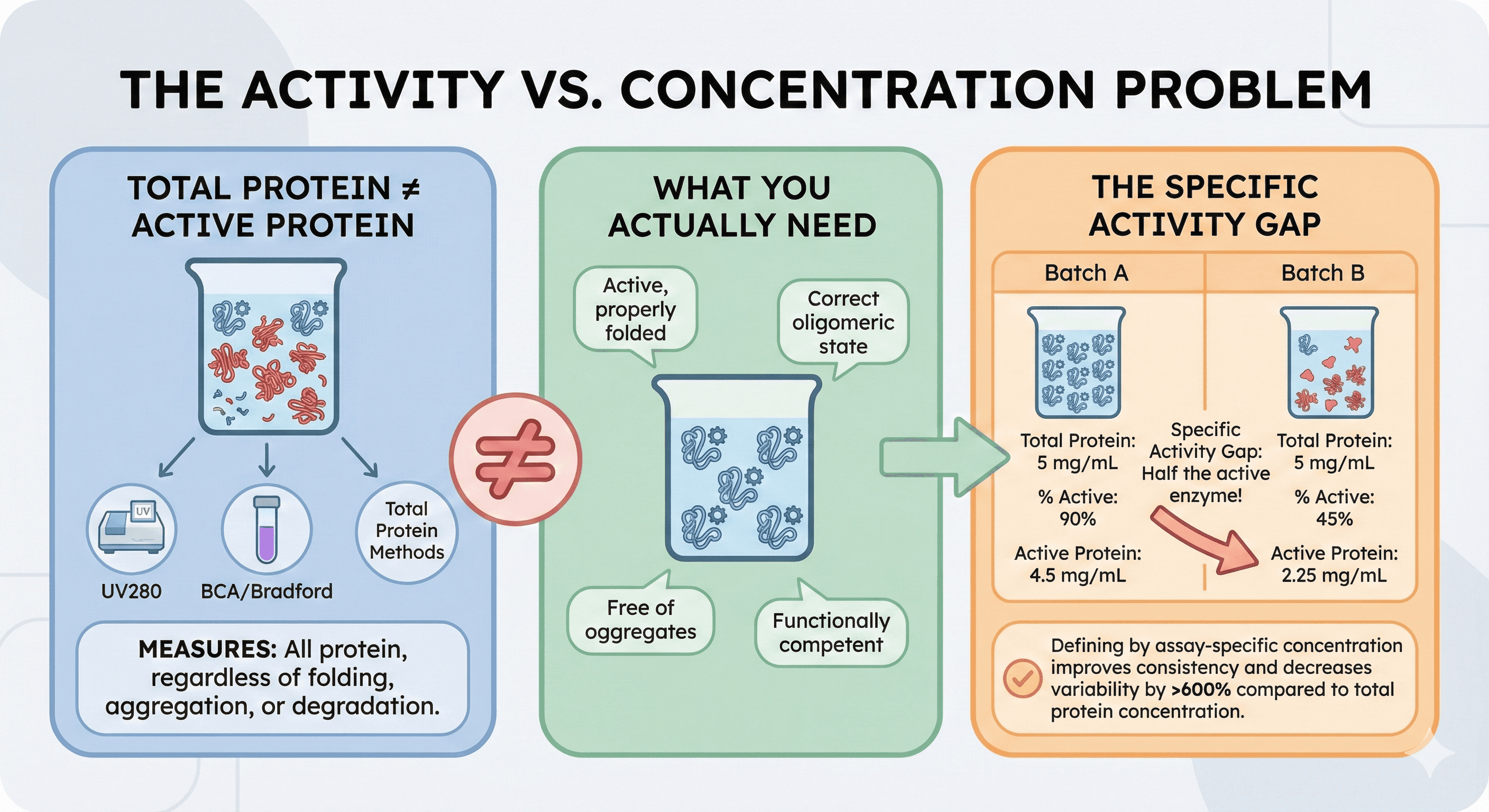

The Activity vs. Concentration Problem

Total Protein ≠ Active Protein

Research has demonstrated that "lot-to-lot differences in protein activity often still occur, leading to uncertainty in the accuracy of downstream measurements. These differences are postulated to be caused by a misrepresentation of the protein concentration as measured by traditional total protein techniques, which can include multiple types of inactive protein species."

What total protein methods (UV280, BCA, Bradford) measure:

All protein, regardless of folding state

Aggregated protein counts the same as native

Inactive protein counts the same as active

Degraded fragments contribute to absorbance

What you actually need:

Active, properly folded protein

In the correct oligomeric state

Free of aggregates

Functionally competent

The Specific Activity Gap

Two batches, both at "5 mg/mL":

Batch | Total Protein | % Active | Active Protein |

|---|---|---|---|

A | 5 mg/mL | 90% | 4.5 mg/mL |

B | 5 mg/mL | 45% | 2.25 mg/mL |

If you normalize experiments by total protein concentration, Batch B has half the active enzyme—and your data won't make sense.

Studies found that "defining protein reagents by their assay-specific concentration improved consistency in reported kinetic binding parameters and decreased immunoassay lot-to-lot coefficients of variation (CVs) by over 600% compared to the total protein concentration."

Measuring Batch-to-Batch Variability

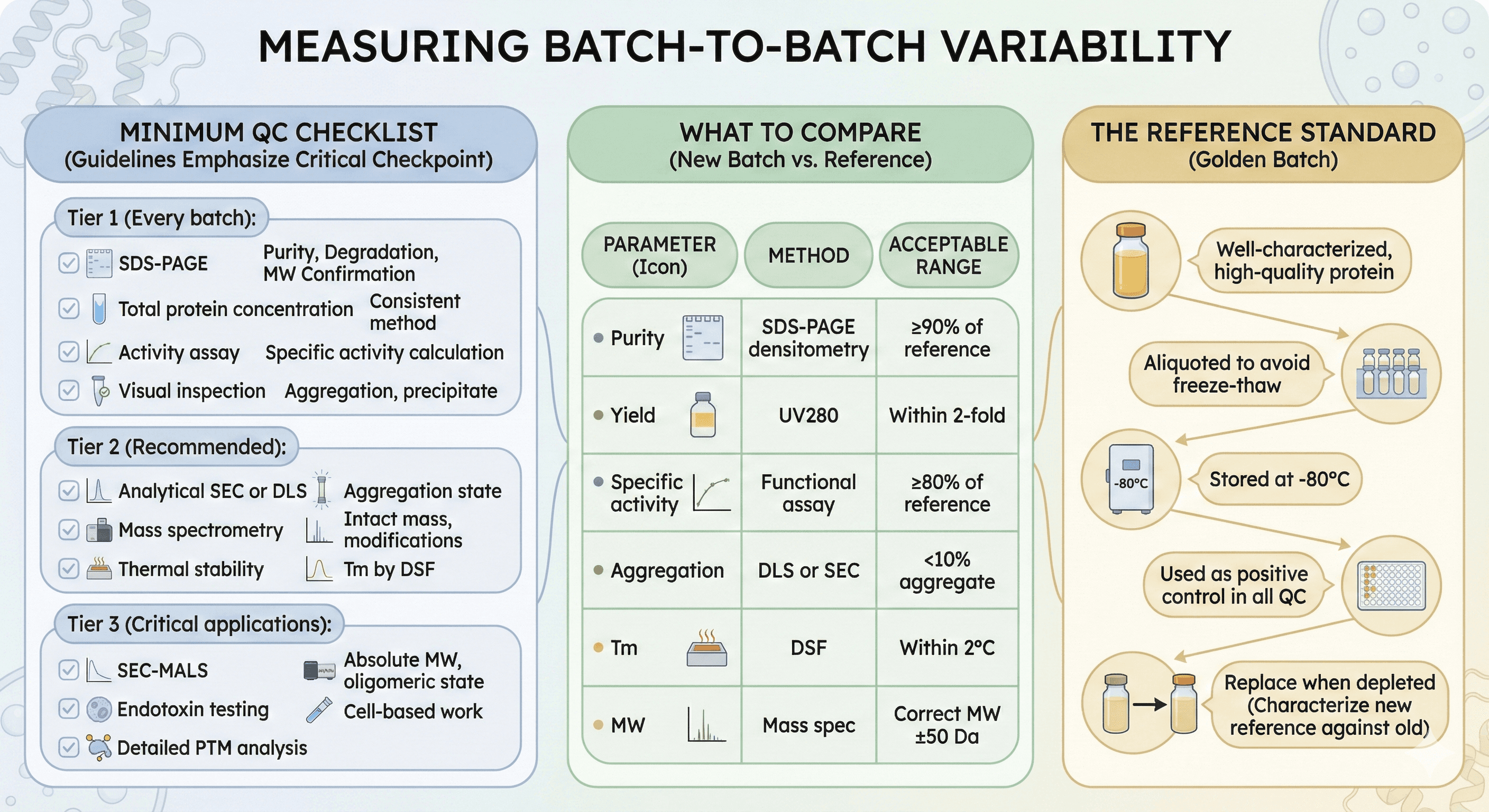

Minimum QC Checklist

Guidelines for protein quality assessment emphasize that "purified protein quality control is the final and critical checkpoint of any protein production process, though it is unfortunately too often overlooked and performed hastily."

Tier 1 (Every batch):

[ ] SDS-PAGE (purity, degradation, MW confirmation)

[ ] Total protein concentration (consistent method)

[ ] Activity assay (specific activity calculation)

[ ] Visual inspection (aggregation, precipitate)

Tier 2 (Recommended):

[ ] Analytical SEC or DLS (aggregation state)

[ ] Mass spectrometry (intact mass, modifications)

[ ] Thermal stability (Tm by DSF)

Tier 3 (Critical applications):

[ ] SEC-MALS (absolute MW, oligomeric state)

[ ] Endotoxin testing (cell-based work)

[ ] Detailed PTM analysis

What to Compare

For each new batch, compare to a reference batch:

Parameter | Method | Acceptable Range |

|---|---|---|

Purity | SDS-PAGE densitometry | ≥90% of reference |

Yield | UV280 | Within 2-fold |

Specific activity | Functional assay | ≥80% of reference |

Aggregation | DLS or SEC | <10% aggregate |

Tm | DSF | Within 2°C |

MW | Mass spec | Correct MW ±50 Da |

The Reference Standard

Keep a reference batch for comparison:

Well-characterized, high-quality protein

Aliquoted to avoid freeze-thaw

Stored at -80°C

Used as positive control in all QC

Replace when depleted (characterize new reference against old)

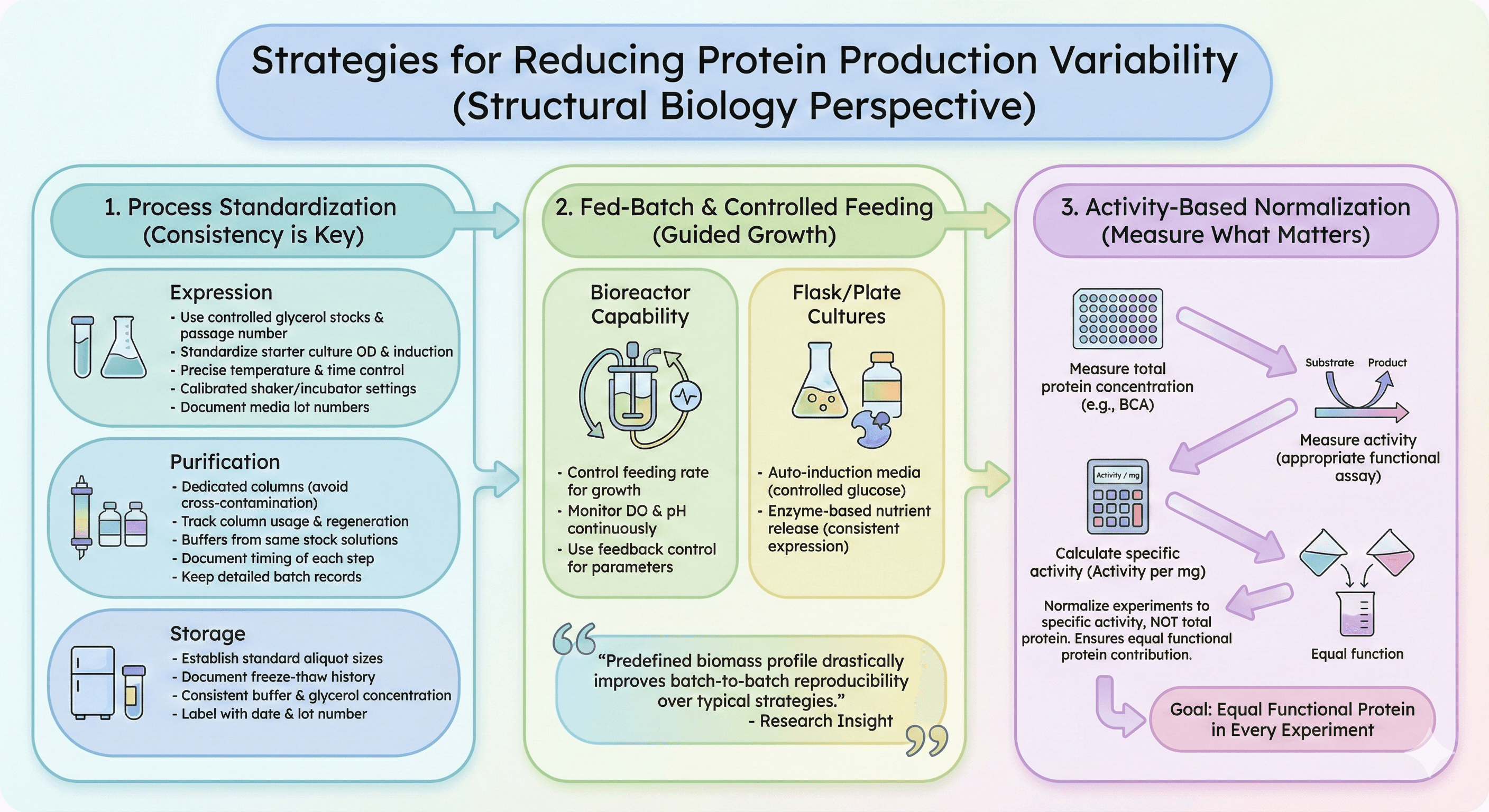

Strategies for Reducing Variability

Process Standardization

Expression:

Use glycerol stocks with controlled passage number

Standardize starter culture protocol (OD at inoculation)

Control induction time and temperature precisely

Use calibrated shaker/incubator settings

Document and control media lot numbers

Purification:

Use dedicated columns (avoid cross-contamination)

Track column usage and regenerate on schedule

Make buffers from same stock solutions within a campaign

Document timing of each step

Keep detailed batch records

Storage:

Establish standard aliquot sizes

Document freeze-thaw history

Use consistent buffer and glycerol concentration

Label with production date and lot number

Fed-Batch and Controlled Feeding

Research has shown that "guiding the process along a predefined profile of the total biomass derived from a given specific growth rate profile" can "drastically improve batch-to-batch reproducibility compared to the process control strategies typically applied in industry."

For labs with bioreactor capability:

Control feeding rate to manage growth rate

Monitor dissolved oxygen and pH continuously

Use feedback control for key parameters

For shaking flask/plate cultures:

Auto-induction media with controlled glucose release reduces variability

Enzyme-based nutrient release provides more consistent expression

Activity-Based Normalization

Don't normalize by total protein—normalize by activity.

For each batch:

Measure total protein concentration

Measure activity (appropriate assay for your protein)

Calculate specific activity (activity per mg)

Normalize experiments to specific activity, not total protein

This ensures that different batches contribute equal functional protein to each experiment.

When Batch Variation Causes Problems

Case 1: The Screening Campaign Disaster

Situation:

HTS campaign over 6 months

4 protein batches used

Batch 3 had 40% lower specific activity (undetected)

All plates from Batch 3 had shifted Z' factor

Consequence:

False negatives from Batch 3 plates

True actives missed

Discovered months later during hit validation

Prevention:

QC every batch before use

Include reference compound on every plate

Monitor assay performance metrics continuously

Case 2: The Irreproducible Structure

Situation:

Batch A crystallized beautifully

Batch B (same protocol) never crystallized

Difference: Batch B had 15% aggregate

Consequence:

Months of failed crystallization trials

Eventually traced to protein batch quality

Prevention:

DLS or analytical SEC on every batch

Set maximum aggregate threshold (<5%)

Re-purify if aggregation too high

Case 3: The Kinetic Constants That Changed

Situation:

Published Km = 50 µM

New batch gives Km = 120 µM

Different postdoc, same protocol

Consequence:

Reproducibility crisis

Revision required (embarrassing)

Discovered: Old batch had contaminating activator

Prevention:

Include positive control in every assay

Side-by-side comparison of old and new batches

Mass spec to verify composition

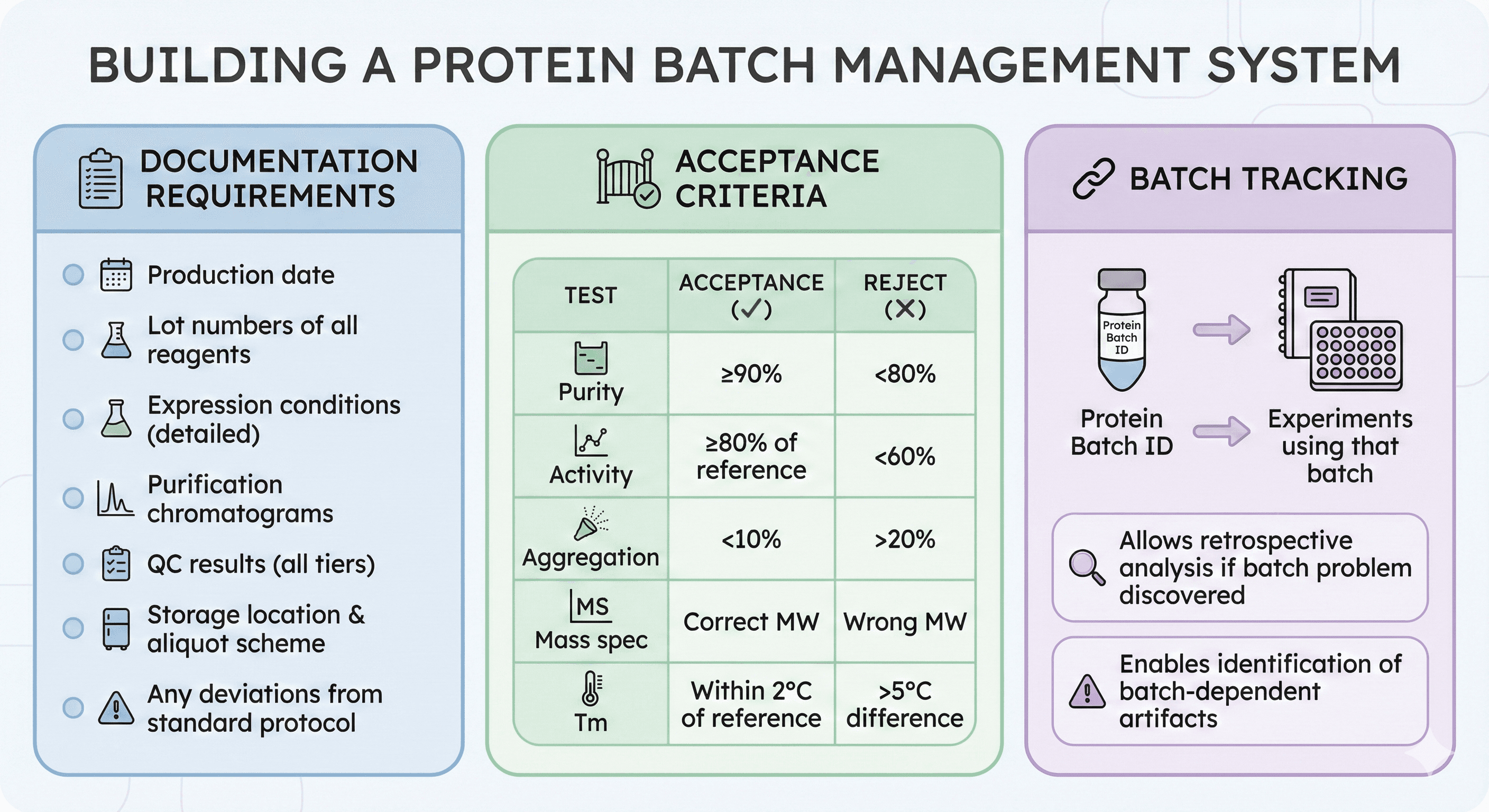

Building a Batch Management System

Documentation Requirements

For each batch, record:

Production date

Lot numbers of all reagents

Expression conditions (detailed)

Purification chromatograms

QC results (all tiers)

Storage location and aliquot scheme

Any deviations from standard protocol

Acceptance Criteria

Before using any batch, verify:

Test | Acceptance | Reject |

|---|---|---|

Purity | ≥90% | <80% |

Activity | ≥80% of reference | <60% |

Aggregation | <10% | >20% |

Mass spec | Correct MW | Wrong MW |

Tm | Within 2°C of reference | >5°C difference |

Batch Tracking

Maintain a log that links:

Protein batch ID → Experiments using that batch

Allows retrospective analysis if batch problem discovered

Enables identification of batch-dependent artifacts

Special Considerations

Multi-Site Collaborations

When sharing protein between labs:

Establish common QC standards

Ship reference standards for side-by-side validation

Compare results from same batch before comparing across batches

Communicate batch changes explicitly

Long-Term Studies

For studies spanning months or years:

Produce large batch at start (if possible)

Characterize extensively

Store carefully to minimize degradation

Have backup plan for producing equivalent batch

Document any batch transitions in publications

Commercial Protein

Even commercial proteins vary lot-to-lot:

Request certificates of analysis

Consider keeping internal standard for comparison

Track lot numbers used in experiments

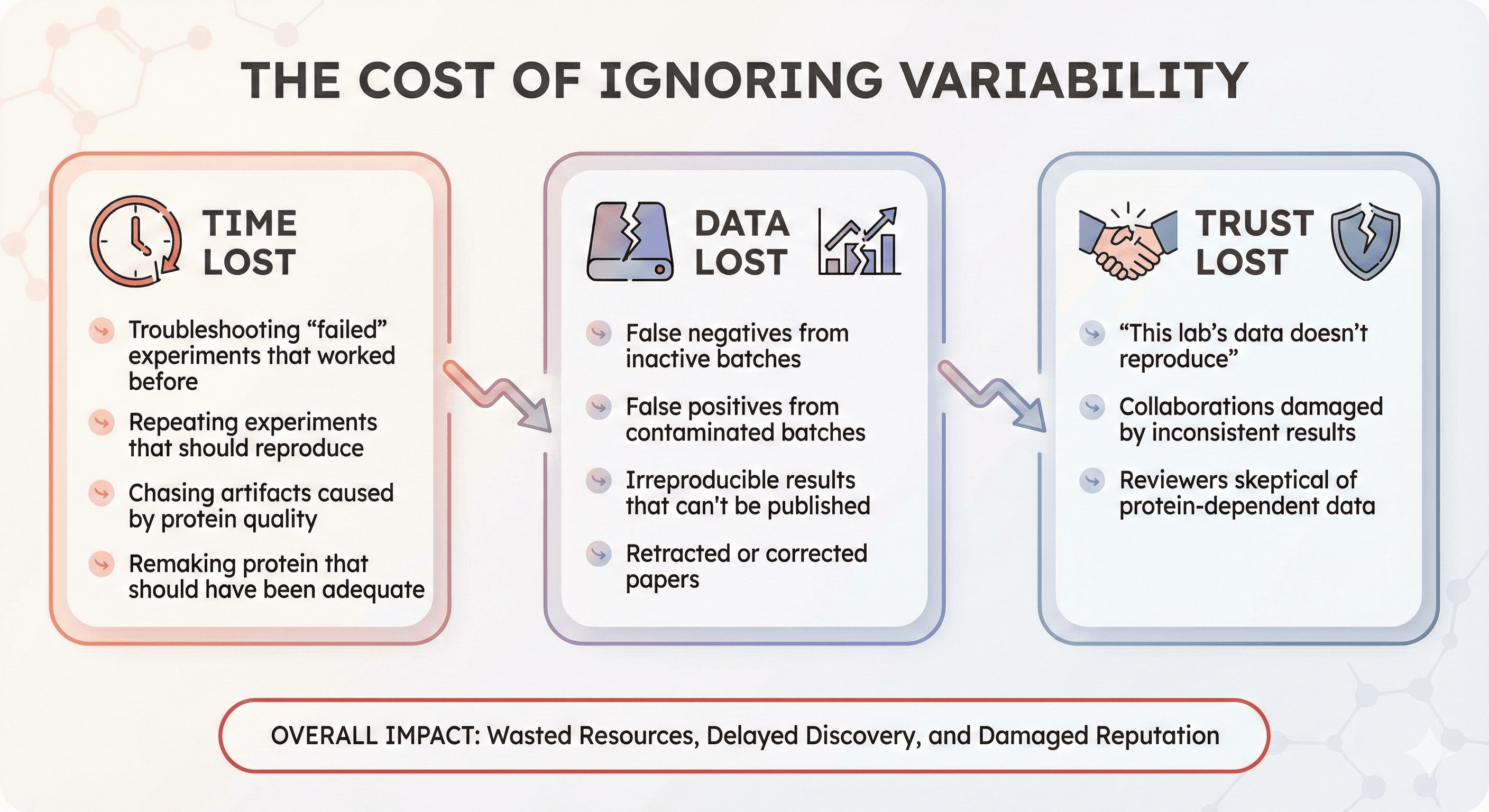

The Cost of Ignoring Variability

Time Lost

Troubleshooting "failed" experiments that worked before

Repeating experiments that should reproduce

Chasing artifacts caused by protein quality

Remaking protein that should have been adequate

Data Lost

False negatives from inactive batches

False positives from contaminated batches

Irreproducible results that can't be published

Retracted or corrected papers

Trust Lost

"This lab's data doesn't reproduce"

Collaborations damaged by inconsistent results

Reviewers skeptical of protein-dependent data

The Bottom Line

Batch-to-batch variability is not randomness you have to accept—it's a technical problem you can manage. The solution requires:

Element | Implementation |

|---|---|

Awareness | Acknowledge that batches vary |

Measurement | QC every batch systematically |

Standardization | Control what you can control |

Documentation | Track batches through all experiments |

Response | Act on QC failures before they contaminate data |

Studies have shown that implementing rigorous quality control of protein reagents dramatically improves research data reproducibility. The investment in QC pays dividends in reproducible, trustworthy data.

The bottom line: If you can't characterize the difference between your batches, you can't interpret the difference between your experiments.

Quality-Focused Protein Analysis

For researchers working to improve batch consistency, platforms like Orbion can help identify characteristics that might contribute to variability:

Aggregation propensity prediction: Flag proteins likely to have variable aggregation behavior

PTM site prediction: Identify modifications that might vary between expression conditions

Stability assessment: Predict regions prone to degradation or instability

Disorder mapping: Understand which regions might contribute to heterogeneity

Understanding your protein's intrinsic properties helps you anticipate and control the sources of batch-to-batch variation—leading to more reproducible protein and more reliable data.

References

Zobel-Roos S, et al. (2019). Economic analysis of batch and continuous biopharmaceutical antibody production: A review. Biotechnology Journal, 14(1):e1700739. PMC6432653

Jungbauer A, et al. (2006). Improving the batch-to-batch reproducibility in microbial cultures during recombinant protein production by guiding the process along a predefined total biomass profile. BMC Biotechnology, 6:35. PMC1705514

Marhöfer RJ, et al. (2024). Overcoming lot-to-lot variability in protein activity using epitope-specific calibration-free concentration analysis. Analytical Chemistry, 96(15):5982-5990. PMC11044105

Raynal B, et al. (2014). Quality assessment and optimization of purified protein samples: why and how? Microbial Cell Factories, 13:180. PMC4299812

Bhambure R, et al. (2021). Quality control of protein reagents for the improvement of research data reproducibility. Nature Communications, 12:2795. Nature

Panula-Perälä J, et al. (2016). The fed-batch principle for the molecular biology lab: controlled nutrient diets in ready-made media improve production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Microbial Cell Factories, 7:31. Link

Hage C, et al. (2019). Recent developments in bioprocessing of recombinant proteins: expression hosts and process development. Bioengineering, 6(4):119. PMC6932962

R&D Systems. (2024). Recombinant protein quality—Protein production. Technical Documentation. Link