Blog

Why High-Throughput Screening Hits Don't Reproduce

Feb 9, 2026

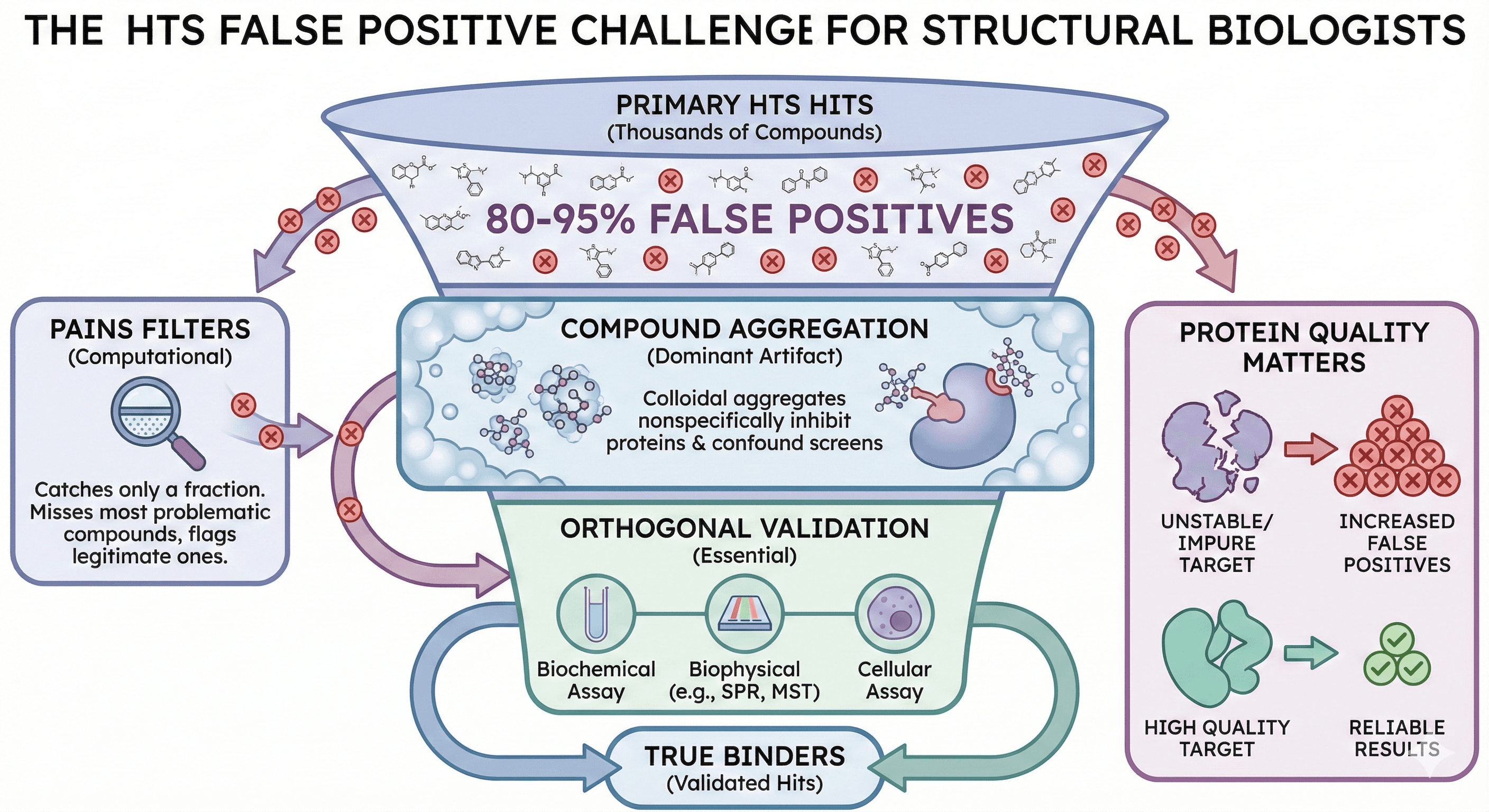

The primary screen identified 847 hits. Dose-response narrowed it to 127 confirmed actives. You cherry-picked the best 20 for follow-up. Six months later, you've tested them all in orthogonal assays. Exactly two show real activity against your target. The other 18 were artifacts, aggregators, or assay interference. A 90% false positive rate—and you're not alone.

This is the reproducibility crisis in high-throughput screening, and it's one of the most expensive problems in early drug discovery.

Key Takeaways

Most HTS hits are false positives: Industry estimates suggest 80-95% of primary hits fail to reproduce in orthogonal assays

Compound aggregation is the dominant artifact: Colloidal aggregates nonspecifically inhibit proteins and confound most biochemical screens

PAINS filters catch only a fraction: Computational filters miss most problematic compounds and flag many legitimate ones

Orthogonal validation is essential: No single assay type can distinguish true binders from artifacts

Protein quality matters: Unstable or impure target protein increases false positive rates dramatically

The False Positive Problem

The Numbers Are Sobering

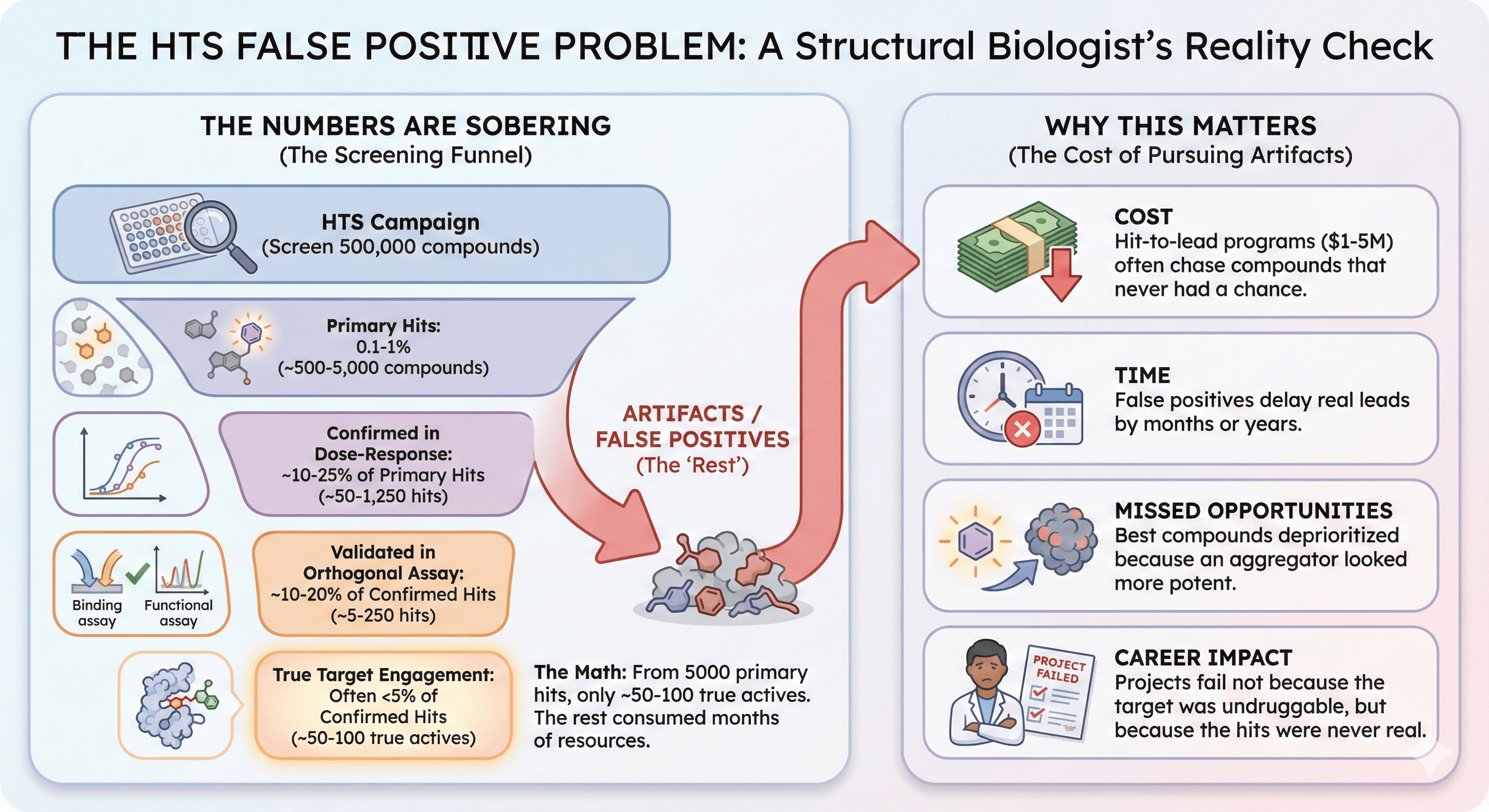

A typical HTS campaign:

Screen 500,000 compounds

Primary hits: 0.1-1% (~500-5000 compounds)

Confirmed in dose-response: ~10-25% of primary hits

Validated in orthogonal assay: ~10-20% of confirmed hits

True target engagement: Often <5% of confirmed hits

The math: From 5000 primary hits, you might get 50-100 true actives. The rest consumed months of chemistry resources pursuing artifacts.

Why This Matters

Cost: Hit-to-lead programs cost $1-5 million. Most are chasing compounds that never had a chance.

Time: False positives delay real leads by months or years.

Missed opportunities: The best compounds might have been deprioritized because an aggregator looked more potent.

Career impact: Projects fail not because the target was undruggable, but because the hits were never real.

The Five Sources of False Positives

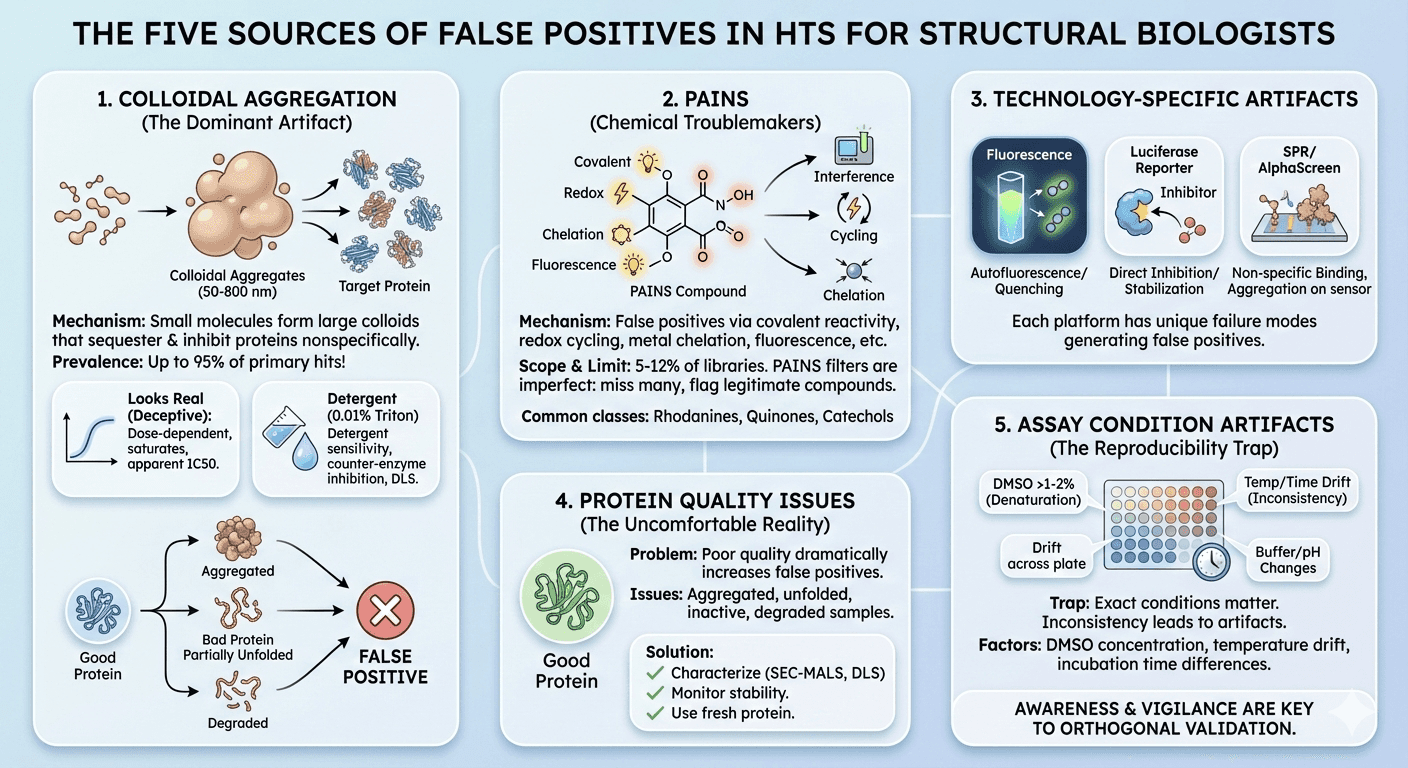

Source 1: Colloidal Aggregation

The mechanism: Many organic molecules—including drugs, clinical candidates, and especially early leads—spontaneously form colloids in aqueous buffer. These aggregates are densely packed particles ranging from 50 to over 800 nm in radius that sequester 10⁵ to 10⁶ protein molecules, leading to their partial denaturation and typically their inhibition.

The prevalence: Studies suggest that aggregation has been reported to occur for up to 95% of primary hits from HTS campaigns. This is the dominant source of false positives in biochemical screens.

The insidious nature: Aggregation-based inhibition looks real:

Dose-dependent (more compound = more aggregates = more inhibition)

Saturates at high concentration

Shows apparent IC50 values

Can be potent (sub-micromolar apparent IC50)

What doesn't distinguish it from true inhibitors:

Apparent potency

Hill slope (often ~1)

Time-dependence (if any)

What does distinguish it:

Detergent sensitivity: Add 0.01-0.1% Triton X-100 or Tween-80; aggregate-based inhibition disappears

Counter-enzyme susceptibility: Aggregators inhibit unrelated enzymes (e.g., AmpC β-lactamase as a counter-screen)

Dynamic light scattering (DLS): Particles visible above critical aggregation concentration

Even cell-based assays aren't immune: Recent research on COVID-19 drug repurposing showed that of 41 tested drugs, 17 behaved as classic aggregators, forming particles by DLS and inhibiting counter-screening enzymes. Colloidal aggregation contributed to false positives in cell-based antiviral screens.

Source 2: Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS)

What PAINS are: PAINS are chemical compounds that give false positive results in many different assay types due to:

Covalent reactivity with proteins

Redox cycling

Metal chelation

Fluorescence interference

Photoreactivity

Common PAINS classes:

Rhodanines

Quinones

Catechols

Isothiazolones

Hydroxyphenyl hydrazones

Curcuminoids

Enones

The scope: Studies estimate that a typical academic screening library contains roughly 5-12% PAINS. There are approximately 400 structural classes of PAINS.

The limitation of PAINS filters: Large-scale analysis found that "the same PAINS substructure was often found in consistently inactive and frequently active compounds, indicating that the structural context in which PAINS occur modulates their effects."

PAINS filters are problematic: they are "oversensitive and disproportionately flag compounds as interference compounds while failing to identify a majority of truly interfering compounds." In other words, they create both false positives and false negatives in compound triage.

Better approaches: Quantitative Structure-Interference Relationship (QSIR) models for specific interference mechanisms (thiol reactivity, redox activity, luciferase activity) show 58-78% external balanced accuracy—better than PAINS filters but still imperfect.

Source 3: Technology-Specific Artifacts

Different assay formats have different vulnerabilities:

Fluorescence-based assays:

Compound autofluorescence (false activation)

Fluorescence quenching (false inhibition)

Inner filter effects at high concentration

Compound fluorescence overlapping with probe

Luciferase reporter assays:

Luciferase inhibition (independent of pathway)

Luciferase stabilization

Compound effects on reporter expression

Redox-active compounds

AlphaScreen/HTRF:

Singlet oxygen scavengers (false inhibition)

Light absorbers

Compound aggregation

Metal chelation affecting donor/acceptor beads

SPR (Surface Plasmon Resonance):

Non-specific binding to chip surface

Aggregation on sensor

Refractive index changes

Compound precipitation in flow

Each technology has specific failure modes that generate false positives unique to that platform.

Source 4: Protein Quality Issues

The problem nobody wants to discuss: Poor protein quality dramatically increases false positive rates:

Protein Issue | How It Causes False Positives |

|---|---|

Aggregated protein | Binds compounds nonspecifically |

Partially unfolded | Exposes normally buried sites |

Inactive fraction | Shifts apparent IC50, flat SAR |

Degraded protein | Cleavage products may have altered binding |

Wrong oligomeric state | Different binding properties |

Missing cofactor | Dead enzyme, artifacts dominate |

The uncomfortable reality: Production of recombinant proteins is often hampered by instability and propensity to aggregate. Protein samples of poor quality are associated with reduced reproducibility.

When your target protein is 30% aggregated, 20% inactive, and slowly degrading during the screen—your data is compromised before a single compound is tested.

What to do:

Characterize protein quality before screening (SEC-MALS, DLS, activity assay)

Monitor stability over screening duration

Use fresh protein batches

Include positive control compounds on every plate

Track Z' factor for quality control

Source 5: Assay Condition Artifacts

The reproducibility trap: The exact conditions of screening matter enormously:

DMSO concentration: Above 1-2%, protein starts denaturing

Buffer composition: pH, ionic strength, divalent cations all affect binding

Temperature: Room temperature assays drift

Incubation time: Equilibrium may not be reached

Protein concentration: Below Kd, binding is hard to detect

Order of addition: Compounds added to protein vs. protein added to compounds

The drift problem: HTS assay validation guidelines emphasize that "plates should not exhibit material edge or drift effects." But in practice, a 384-well plate takes time to fill, and conditions change:

First wells incubate longer than last wells

Reagents in reservoirs warm up

DMSO evaporates, changing final concentration

Enzyme activity decays during plate setup

The Validation Cascade

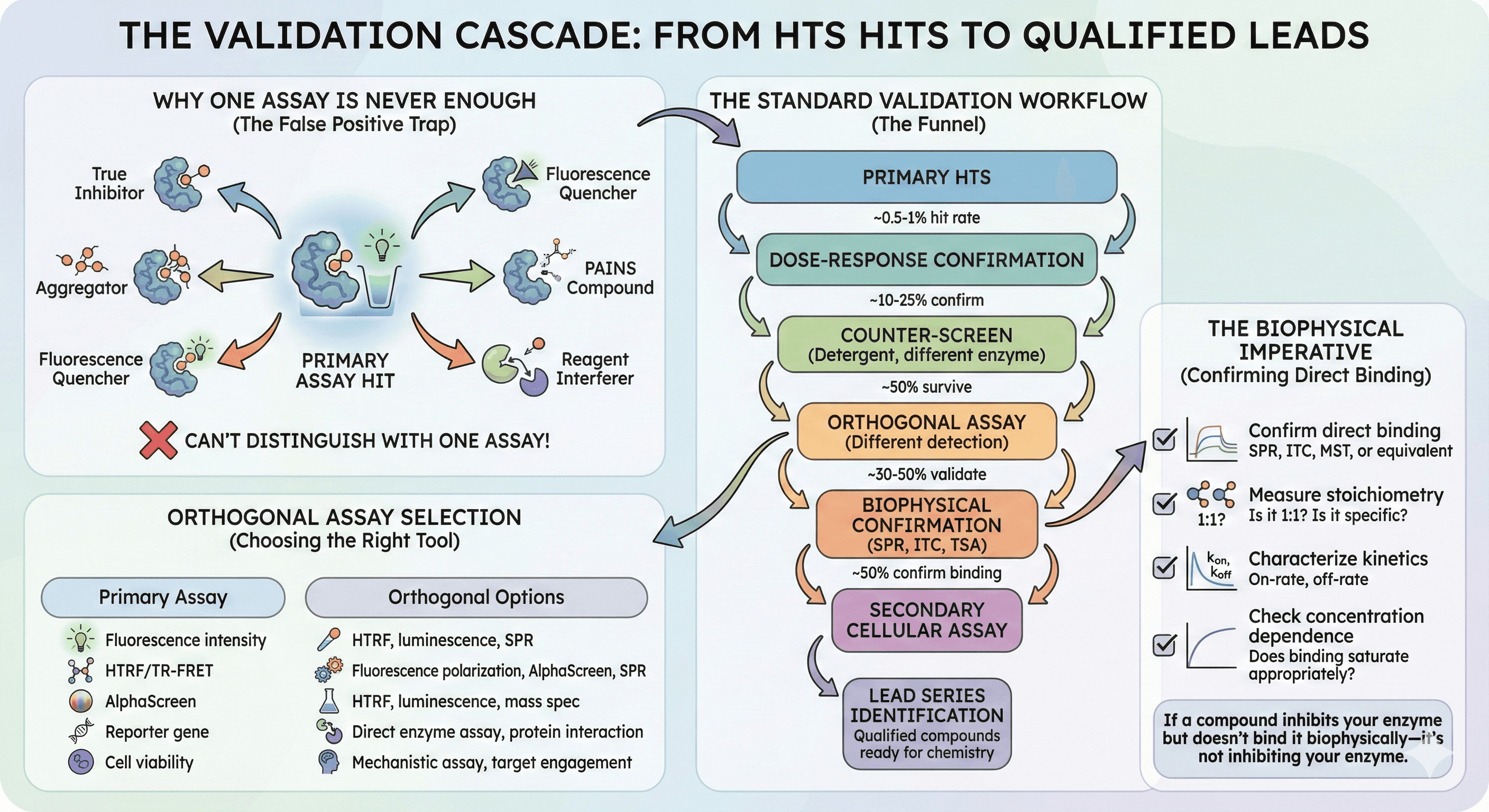

Why One Assay Is Never Enough

A compound that inhibits your target in a fluorescence assay might be:

A true inhibitor

An aggregator

A fluorescence quencher

A PAINS compound that reacts with your target (but also everything else)

A compound that affects assay reagents

You can't distinguish these with a single assay format.

The Standard Validation Workflow

Each step reduces compound numbers by 50-80%.

Orthogonal Assay Selection

The second assay should:

Use a different detection technology

Measure the same biochemical event

Be insensitive to the artifacts of the first assay

Primary Assay | Orthogonal Options |

|---|---|

Fluorescence intensity | HTRF, luminescence, SPR |

HTRF/TR-FRET | Fluorescence polarization, AlphaScreen, SPR |

AlphaScreen | HTRF, luminescence, mass spec |

Reporter gene | Direct enzyme assay, protein interaction |

Cell viability | Mechanistic assay, target engagement |

The Biophysical Imperative

For any hit going into chemistry:

Confirm direct binding: SPR, ITC, MST, or equivalent

Measure stoichiometry: Is it 1:1? Is it specific?

Characterize kinetics: On-rate, off-rate

Check concentration dependence: Does binding saturate appropriately?

If a compound inhibits your enzyme but doesn't bind it biophysically—it's not inhibiting your enzyme.

Counter-Screens That Work

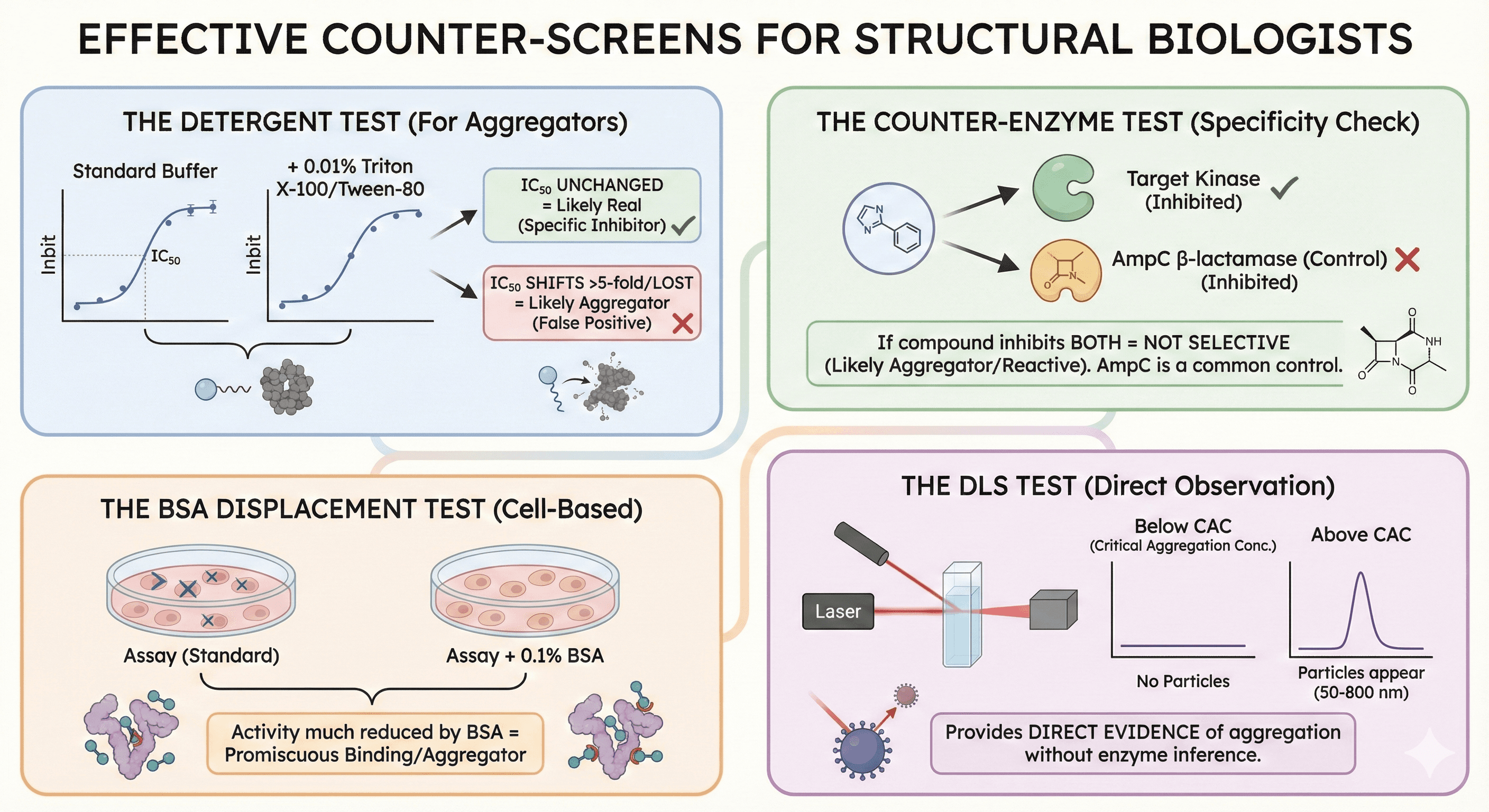

The Detergent Test

Simple and effective for aggregators:

Run dose-response in standard buffer

Run dose-response with 0.01% Triton X-100 or Tween-80

Compare IC50 values

Interpretation:

IC50 unchanged: Likely real

IC50 shifts >5-fold or activity lost: Likely aggregator

Research has shown that this counter-screen reliably detects aggregate-based inhibition because non-ionic detergent disrupts the colloidal aggregates.

The Counter-Enzyme Test

Use an unrelated enzyme as a control: If your compound inhibits both your target kinase AND AmpC β-lactamase—it's not selective. It's probably an aggregator or reactive compound.

AmpC β-lactamase is commonly used because it's extensively characterized for aggregate-based inhibition.

The BSA Displacement Test

For cell-based assays: Run assay with and without 0.1% BSA (bovine serum albumin). Compounds whose activity is much reduced by BSA addition may be aggregators or have promiscuous protein binding.

The DLS Test

Direct observation of aggregation: Measure particle size by dynamic light scattering:

Below critical aggregation concentration: No particles

Above CAC: Particles appear (50-800 nm)

DLS provides direct evidence of aggregation without inference from enzyme inhibition.

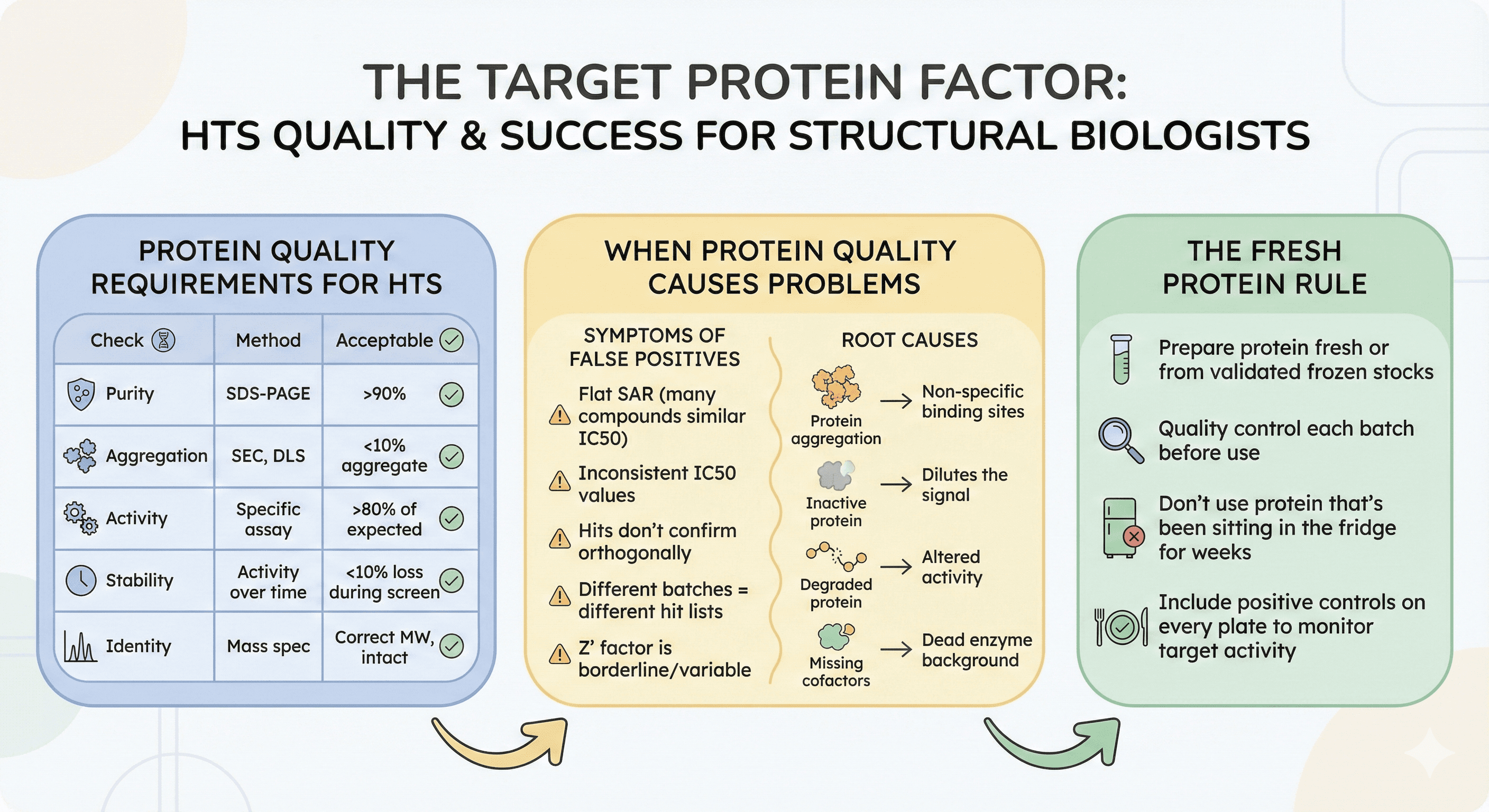

The Target Protein Factor

Protein Quality Requirements for HTS

Before screening, verify:

Check | Method | Acceptable |

|---|---|---|

Purity | SDS-PAGE | >90% |

Aggregation | SEC, DLS | <10% aggregate |

Activity | Specific assay | >80% of expected |

Stability | Activity over time | <10% loss during screen |

Identity | Mass spec | Correct MW, intact |

When Protein Quality Causes Problems

Symptoms of protein-derived false positives:

Flat SAR (many compounds have similar IC50)

IC50 values inconsistent with biochemical understanding

Hits don't confirm in orthogonal assays

Different protein batches give different hit lists

Z' factor is borderline or variable

Root causes:

Protein aggregation creates non-specific binding sites

Inactive protein dilutes the signal

Degraded protein has altered activity

Missing cofactors create dead enzyme background

The Fresh Protein Rule

For critical screens:

Prepare protein fresh or from validated frozen stocks

Quality control each batch before use

Don't use protein that's been sitting in the fridge for weeks

Include positive controls on every plate to monitor target activity

Case Studies in False Positives

Case 1: The Aggregator Epidemic

Screen: Kinase inhibitor HTS, 300,000 compounds Primary hits: 2,400 compounds (0.8%) Dose-response confirmed: 480 compounds (20%) After detergent counter-screen: 96 compounds (20% of confirmed) After SPR: 28 compounds confirmed binding (6% of original confirmed hits)

Lesson: 80% of confirmed hits were aggregators, eliminated by a simple detergent test.

Case 2: The Luciferase Artifact

Screen: Reporter gene assay for pathway activation Primary hits: 150 activators Counter-screen (constitutive luciferase): 120 also activated control reporter True pathway activators: 30 compounds (20% of hits)

Lesson: 80% of "activators" were stabilizing luciferase, not activating the pathway.

Case 3: The Fluorescent Compound

Screen: Fluorescence polarization for protein-protein interaction inhibitor Top hit: Apparent IC50 = 100 nM, beautiful dose-response Orthogonal SPR: No binding detected Investigation: Compound was fluorescent at assay wavelength, creating artifact

Lesson: The most potent hit was completely artifactual.

Case 4: The Protein Quality Problem

Screen: Enzyme inhibitor, fluorescence-based First campaign (old protein): 450 hits, 5% confirmed in orthogonal Second campaign (fresh protein): 180 hits, 35% confirmed in orthogonal

Lesson: Degraded protein had 2.5× more hits, but 7× fewer real ones.

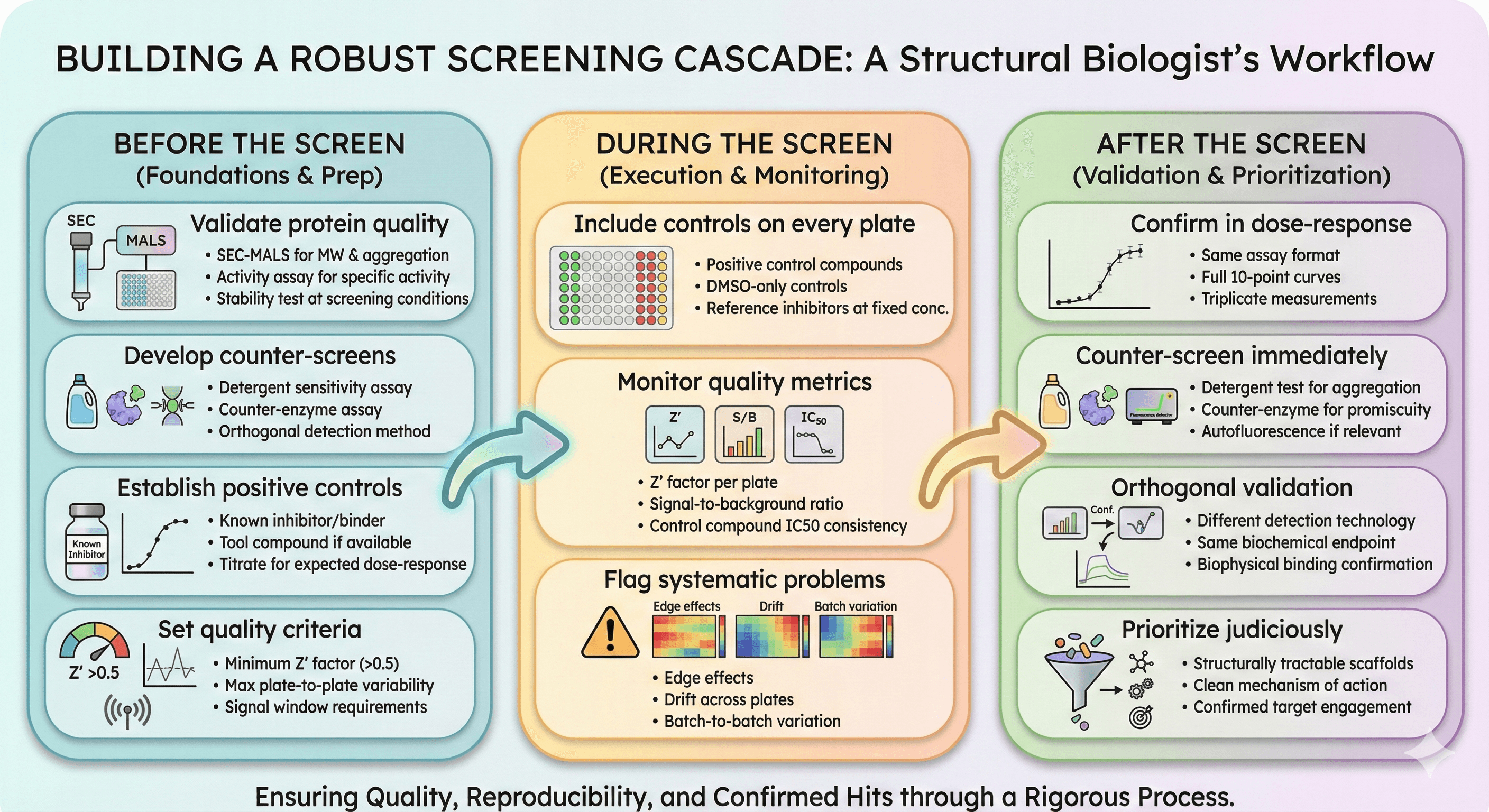

Building a Robust Screening Cascade

Before the Screen

Validate protein quality

SEC-MALS for MW and aggregation

Activity assay for specific activity

Stability test at screening conditions

Develop counter-screens

Detergent sensitivity assay

Counter-enzyme assay

Orthogonal detection method

Establish positive controls

Known inhibitor/binder

Tool compound if available

Titrate to establish expected dose-response

Set quality criteria

Minimum Z' factor (typically >0.5)

Maximum plate-to-plate variability

Signal window requirements

During the Screen

Include controls on every plate

Positive control compounds

DMSO-only controls

Reference inhibitors at fixed concentration

Monitor quality metrics

Z' factor per plate

Signal-to-background ratio

Control compound IC50 consistency

Flag systematic problems

Edge effects

Drift across plates

Batch-to-batch variation

After the Screen

Confirm in dose-response

Same assay format

Full 10-point curves

Triplicate measurements

Counter-screen immediately

Detergent test for aggregation

Counter-enzyme for promiscuity

Autofluorescence if relevant

Orthogonal validation

Different detection technology

Same biochemical endpoint

Biophysical binding confirmation

Prioritize judiciously

Structurally tractable scaffolds

Clean mechanism of action

Confirmed target engagement

The Bottom Line

False positives are not failures of the screen—they're expected outcomes that require systematic elimination. The question isn't whether you'll have false positives (you will); it's whether you'll identify them before investing months in medicinal chemistry.

Prevention Strategy | Implementation |

|---|---|

Aggregation | Detergent counter-screen, DLS |

PAINS | Structural filters (with caution), QSIR models |

Technology artifacts | Orthogonal assay validation |

Protein quality | QC before screening, batch-to-batch controls |

Assay artifacts | Robust validation, positive controls |

The key insight: A hit is not a hit until it's validated by orthogonal methods. Primary screening identifies candidates for investigation—not compounds ready for optimization.

Target Validation for Screening Campaigns

For researchers planning HTS campaigns, understanding your target protein is the first line of defense against false positives. Platforms like Orbion can help with:

Aggregation propensity prediction: Identify whether your target is likely to aggregate, affecting assay performance

Binding site analysis: Understand the druggable pockets you're screening against

Protein stability assessment: Predict regions that may cause instability during screening

PTM requirements: Identify modifications that might be essential for proper target behavior

Better target understanding leads to better assay design, which leads to fewer false positives—saving months of wasted effort chasing artifacts.

References

Shoichet BK. (2006). Screening in a spirit haunted world. Drug Discovery Today, 11(13-14):607-615. PMC4646424

Owen SC, et al. (2012). Colloidal aggregation causes inhibition of G protein-coupled receptors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 55(16):7203-7211. PMC3613083

Feng BY & Bhatt R. (2006). A detergent-based assay for the detection of promiscuous inhibitors. Nature Protocols, 1(2):550-553. PMC1544377

Tran H, et al. (2023). Colloidal aggregation confounds cell-based Covid-19 antiviral screens. ACS Chemical Biology, 18(10):2332-2342. PMC10634915

Baell JB & Holloway GA. (2010). New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 53(7):2719-2740.

Jasial S, et al. (2017). How frequently are pan-assay interference compounds active? Large-scale analysis of screening data reveals diverse activity profiles, low global hit frequency, and many consistently inactive compounds. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 60(9):3879-3886. Link

Baell JB & Walters MA. (2014). Chemical con artists foil drug discovery. Nature, 513:481-483. Link

Schorpp K, et al. (2020). High-throughput screening to predict chemical-assay interference. Scientific Reports, 10:3839. Link

Iversen PW, et al. (2012). HTS assay validation. In: Assay Guidance Manual. Eli Lilly & Company and NIH NCATS. NCBI Bookshelf

Raynal B, et al. (2022). Measuring protein aggregation and stability using high-throughput biophysical approaches. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 9:890862. Link