Blog

Your Protein Is a Dimer in Solution But a Monomer in the Crystal

Feb 6, 2026

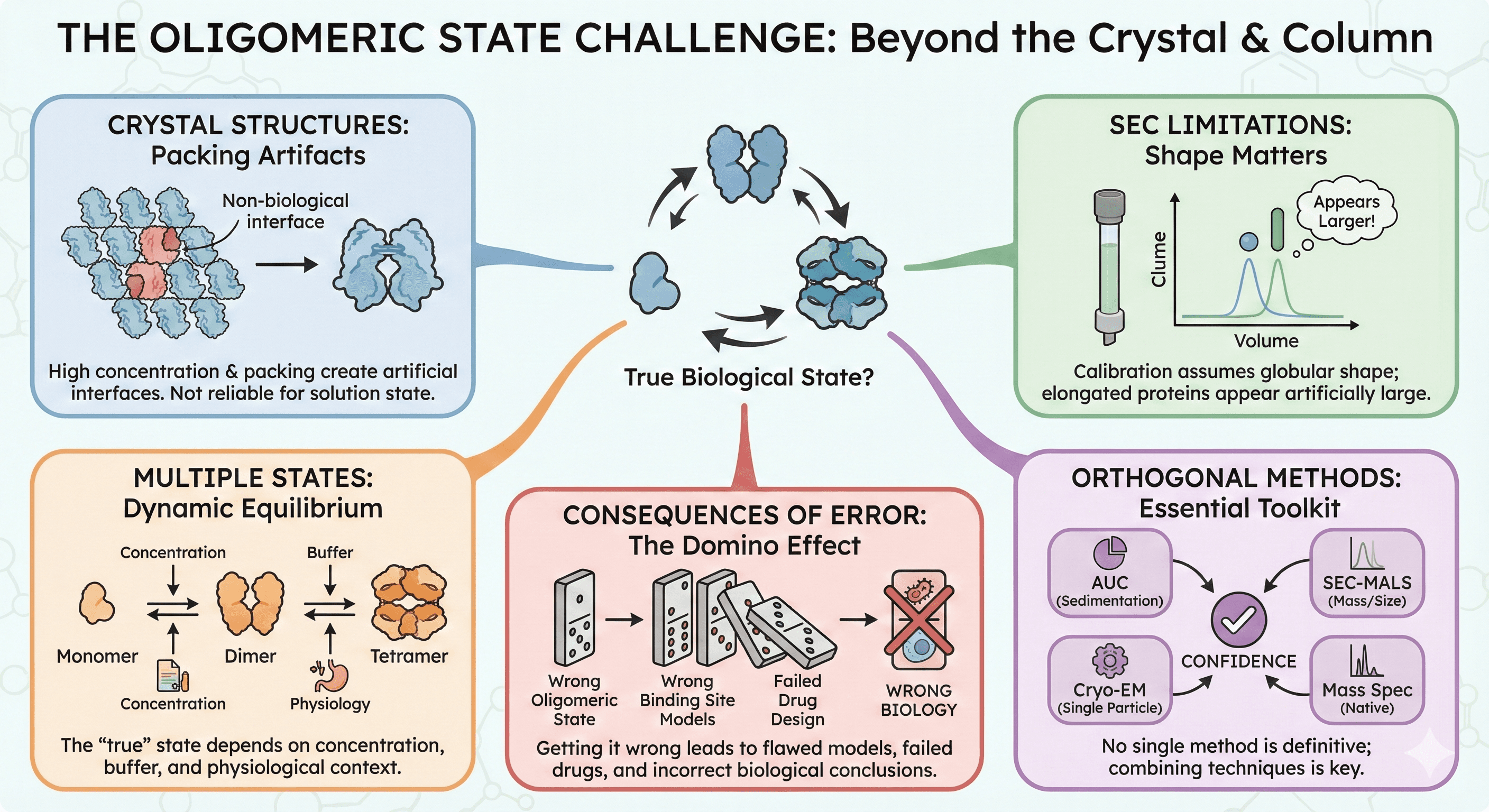

The SEC column says your protein is 85 kDa—clearly a dimer of your 42 kDa subunit. You solve the crystal structure. It's a monomer. The crystallographers say the oligomeric state is artifactual. The biochemists say the crystal is wrong. Both are confident. Both might be right—or both might be wrong.

Determining the true oligomeric state of a protein is harder than it looks, and discrepancies between methods are disturbingly common.

Key Takeaways

Crystal structures don't reliably report oligomeric state: High protein concentration and crystal packing create artificial interfaces

SEC is not a gold standard: Calibration curves assume globular shape; elongated proteins appear larger than they are

Most proteins exist in multiple oligomeric states: The "true" state depends on concentration, buffer, and physiological context

No single method is definitive: Orthogonal techniques are essential

Getting it wrong has consequences: Wrong oligomeric state means wrong binding site models, wrong drug design, wrong biology

The Oligomeric State Problem

Why Oligomeric State Matters

The oligomeric state determines:

Active site architecture: Many enzymes have active sites at subunit interfaces

Allosteric regulation: Cooperativity requires multi-subunit assemblies

Binding stoichiometry: A dimer has different binding properties than a monomer

Drug design: Targeting interfaces requires knowing what interfaces exist

Physiological function: Oligomers and monomers often have different functions

Get the oligomeric state wrong, and everything downstream is suspect.

The Measurement Challenge

Every method for determining oligomeric state has limitations:

Method | Measures | Assumption | Problem |

|---|---|---|---|

SEC | Elution volume | Globular shape | Elongated proteins look bigger |

Crystal structure | Lattice contacts | Biological vs. crystal contact | Hard to distinguish |

DLS | Hydrodynamic radius | Single species | Averages over mixtures |

AUC | Sedimentation coefficient | Homogeneous sample | Requires expertise |

Native MS | Mass | Survives ionization | Gas-phase artifacts |

Crosslinking | Proximity | Specific crosslinking | Non-specific crosslinks |

The Crystal Structure Problem

Why Crystals Lie About Oligomeric State

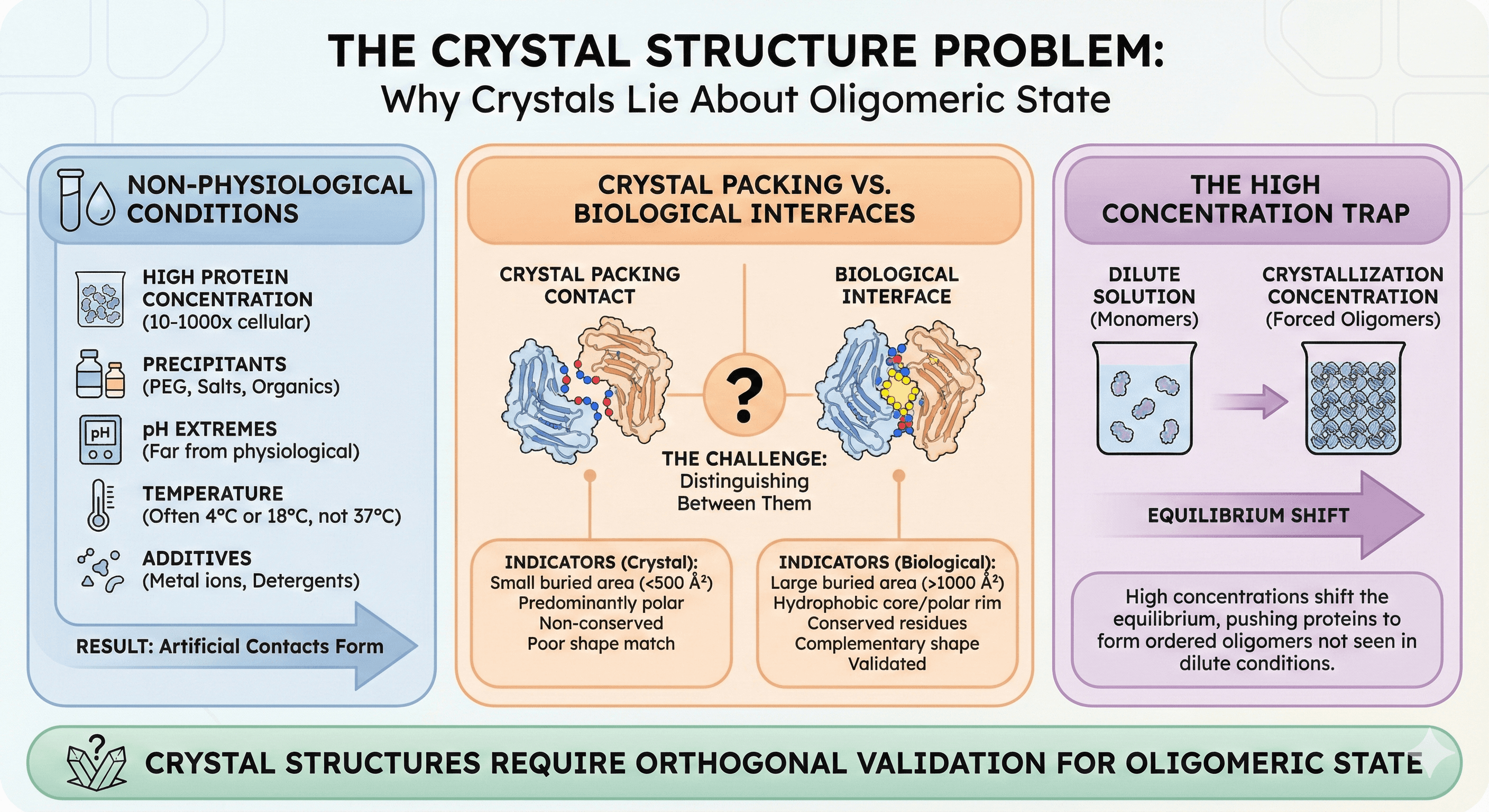

Crystallization conditions are non-physiological:

High protein concentration: 10-50 mg/mL, often 100-1000× higher than cellular

Precipitants: PEG, salts, organic solvents alter interactions

pH extremes: Many crystals grow at pH values far from physiological

Temperature: Often 4°C or 18°C, not 37°C

Additives: Metal ions, detergents can bridge subunits

The result: Proteins form contacts in crystals that don't exist in solution.

Crystal Packing vs. Biological Interfaces

Every protein crystal has multiple protein-protein contacts—that's what makes it a crystal. Studies have shown that "artificially large oligomers may be incorrectly deduced from examination of the protein–protein contacts in the crystalline environment: many of these interactions are nonspecific and simply reflect facile ways of arranging the macromolecule in a regularly ordered lattice."

The challenge: Distinguishing biological interfaces from crystal-packing contacts.

Indicators of biological interfaces:

Large buried surface area (>1000 Ų)

Hydrophobic core with polar rim

Conserved residues at interface

Complementary shape

Interface validated by other methods

Indicators of crystal contacts:

Small buried surface area (<500 Ų)

Predominantly polar

Non-conserved residues

Poor shape complementarity

Not seen in other crystal forms

The High Concentration Trap

Research on oligomeric states has demonstrated that "crystallography has limitations in determining quaternary structure, as crystallization conditions optimize for perfect order, which is achieved at high protein concentrations and solution additives (salt and crowders). These may push the proteins to form an ordered, homogeneous lattice."

Proteins that are monomers in dilute solution may form dimers or higher oligomers at crystallization concentrations simply because the equilibrium shifts.

The SEC Problem

Why SEC Lies About Oligomeric State

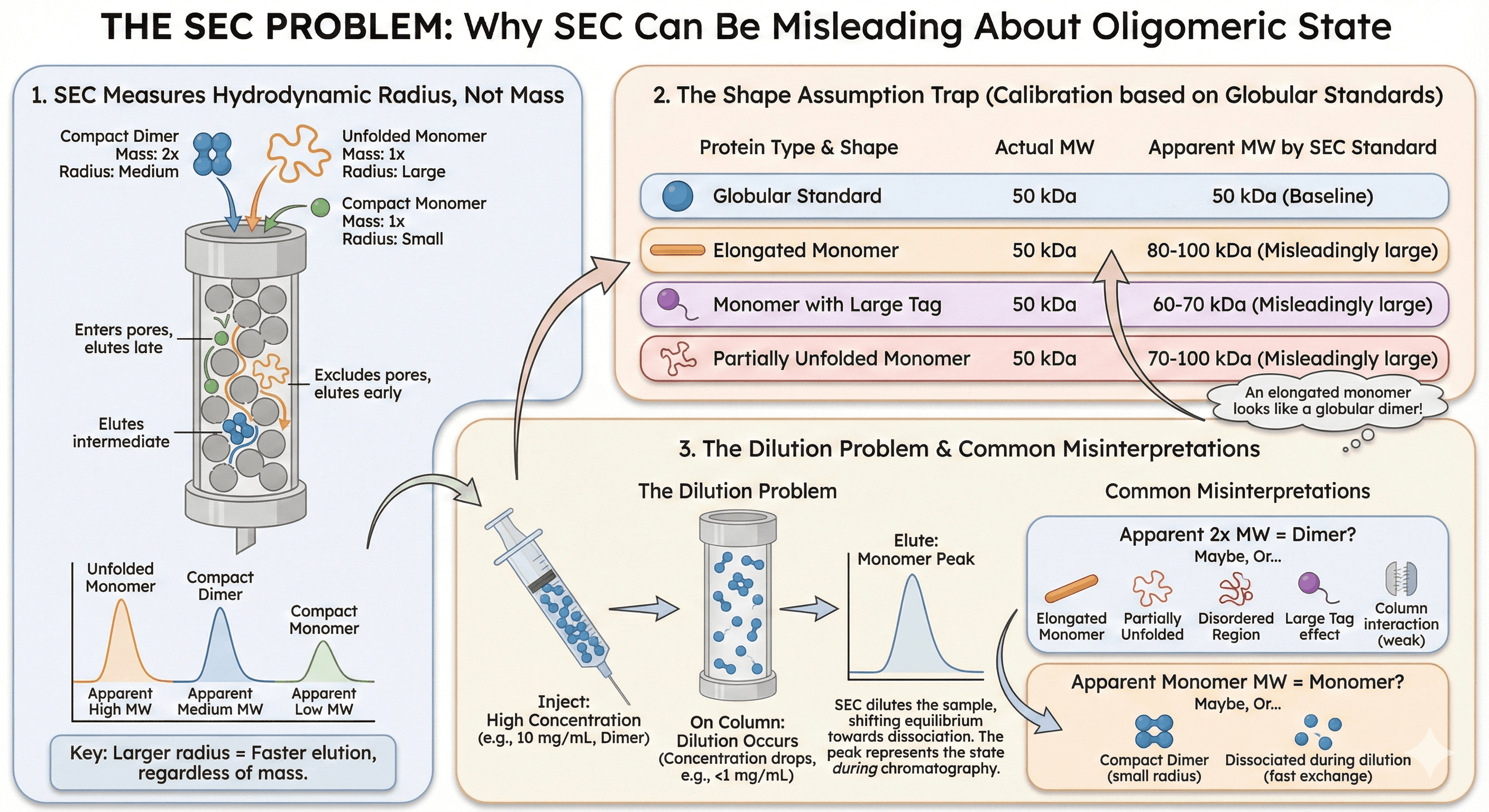

Size exclusion chromatography is the most common method for assessing oligomeric state. It's fast, easy, and gives a clear answer.

The problem: SEC doesn't measure mass—it measures hydrodynamic radius.

The Shape Assumption

SEC calibration uses globular protein standards. This creates systematic errors:

Protein Shape | Actual MW | Apparent MW by SEC |

|---|---|---|

Globular | 50 kDa | 50 kDa |

Elongated | 50 kDa | 80-100 kDa |

With large tag | 50 kDa | 60-70 kDa |

Partially unfolded | 50 kDa | 70-100 kDa |

An elongated monomer looks like a globular dimer.

Common Misinterpretations

"My protein runs at 2× the expected molecular weight—it must be a dimer"

Maybe. Or:

It's an elongated monomer

It's partially unfolded

It has a disordered region that increases hydrodynamic radius

The tag adds more volume than expected

It interacts weakly with the column matrix

"My protein runs at exactly the expected monomer MW—it's definitely a monomer"

Maybe. Or:

It's a compact dimer with half the expected hydrodynamic radius

Dimer dissociates during chromatography due to dilution

The dimer is in fast exchange and you're seeing average behavior

The Dilution Problem

SEC dilutes the sample as it passes through the column. For proteins with concentration-dependent oligomerization:

Inject: 10 mg/mL (dimer)

On column: <1 mg/mL (monomer)

Elute: monomer peak

The SEC tells you about the oligomeric state during chromatography, not before it.

The Reality: Multiple States Coexist

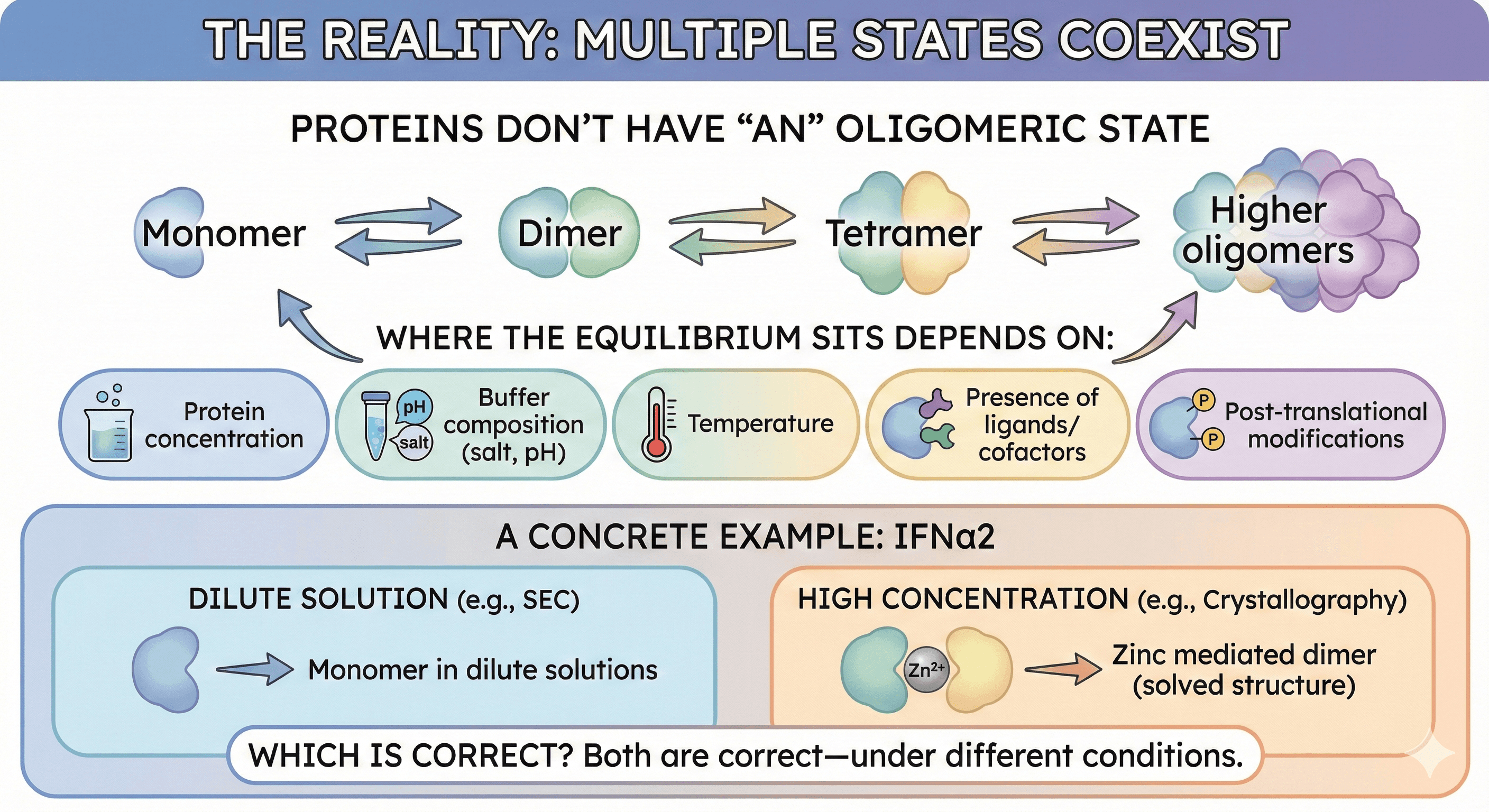

Proteins Don't Have "An" Oligomeric State

A systematic study comparing 17 proteins using multiple methods found that "it would be wrong to assign a single oligomeric state to proteins. Most proteins appear in more than one state. Moreover, of the selected 17 proteins, none is solely in a monomeric state at all protein concentrations."

The equilibrium:

Where the equilibrium sits depends on:

Protein concentration

Buffer composition (salt, pH)

Temperature

Presence of ligands/cofactors

Post-translational modifications

A Concrete Example: IFNα2

Research showed that "the SEC elution volume of IFNα2 is reduced at higher protein-concentrations, suggesting a higher oligomeric state at higher protein concentration. Indeed, while IFNα2 is a monomer in dilute solutions, it was solved as a zinc mediated dimer by X-ray crystallography."

Which is correct? Both are correct—under different conditions.

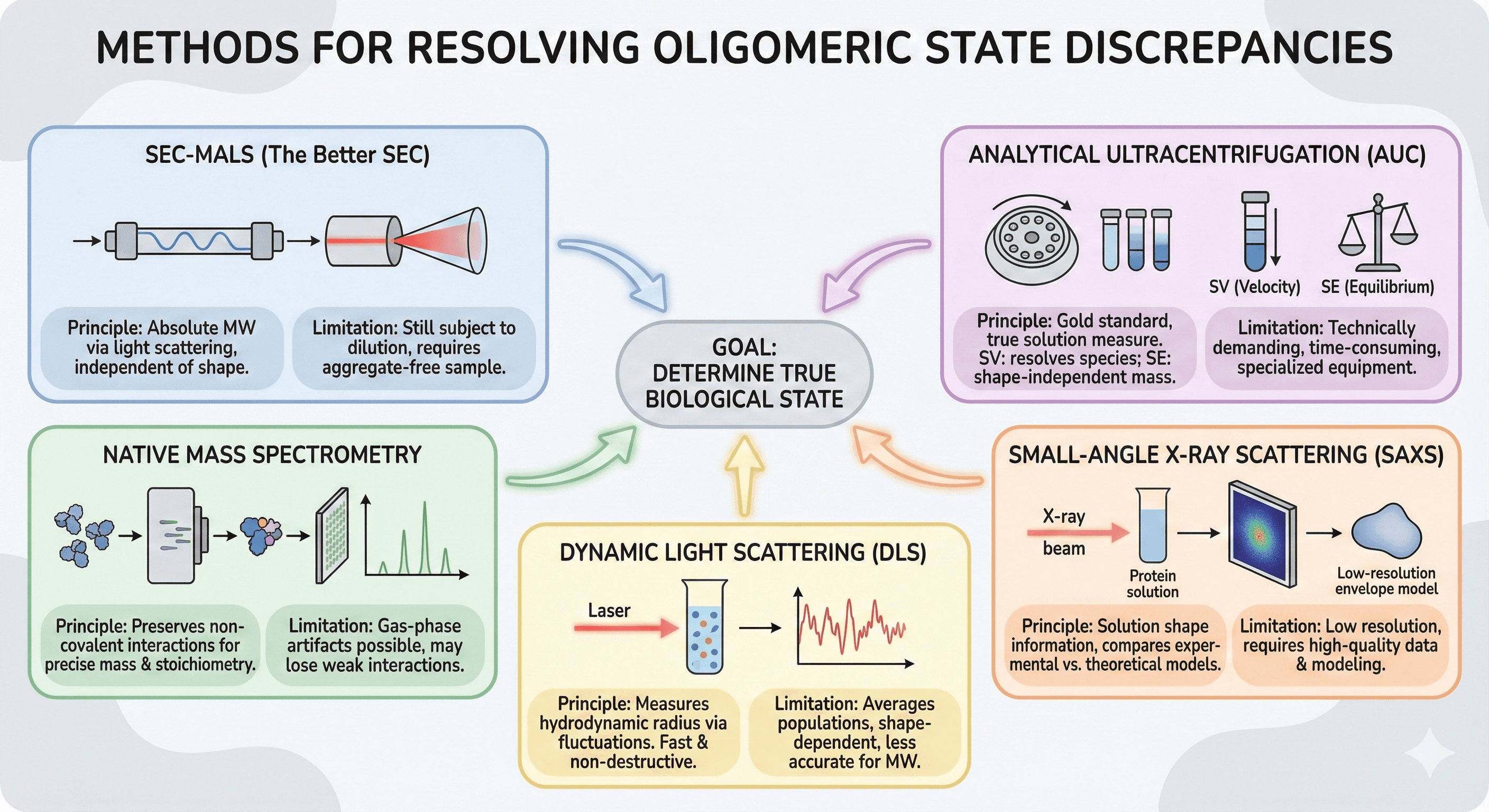

Methods for Resolving Discrepancies

SEC-MALS (The Better SEC)

Multi-angle light scattering (MALS) coupled to SEC provides absolute molecular weight, independent of shape.

Advantages:

Directly measures MW from light scattering

Doesn't require calibration standards

Works for non-globular proteins

Provides polydispersity information

Limitations:

Requires clean, aggregate-free samples

Still subject to dilution effects

Higher oligomers may dissociate on column

Rule of thumb: Designed proteins with measured oligomeric mass within ≤13% of expected are considered validated.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC)

AUC remains the gold standard for rigorous oligomeric state determination.

Sedimentation velocity (SV): Resolves species by sedimentation coefficient, allowing clear separation and quantification of monomers, oligomers, and aggregates in solution.

Sedimentation equilibrium (SE): Directly measures macromolecular mass independent of shape, making it "the method of choice for molar mass determinations and the study of self-association."

Advantages:

True solution measurement (no matrix interaction)

Can characterize equilibria between oligomeric states

Shape-independent mass determination (SE)

High resolution (SV)

Limitations:

Requires specialized equipment

Technically demanding

Time-consuming (hours to days)

Limited throughput

Native Mass Spectrometry

Native MS preserves non-covalent interactions, allowing direct determination of oligomeric state.

Advantages:

Precise mass measurement

Can resolve heterogeneous populations

Stoichiometry directly determined

Works with small sample amounts

Limitations:

Requires specialized instrumentation

Gas-phase artifacts possible

May not preserve weak interactions

Membrane proteins challenging

Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS)

SAXS provides low-resolution structural information in solution.

For oligomeric state: The quaternary structure can be deduced by comparing experimental SAXS curves to theoretical curves calculated from proposed models. This approach is especially robust when the crystal structure is known.

Advantages:

Solution measurement at relevant concentrations

Provides shape information

Can model flexible regions

Works with most proteins

Limitations:

Low resolution

Requires high-quality data

Heterogeneous samples problematic

Data interpretation requires modeling

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

DLS measures hydrodynamic radius in solution.

Advantages:

Fast (minutes)

Non-destructive

Small sample volume

Good for detecting aggregation

Limitations:

Averages over populations

Can't resolve similar-sized species

Shape-dependent

Less accurate for MW determination

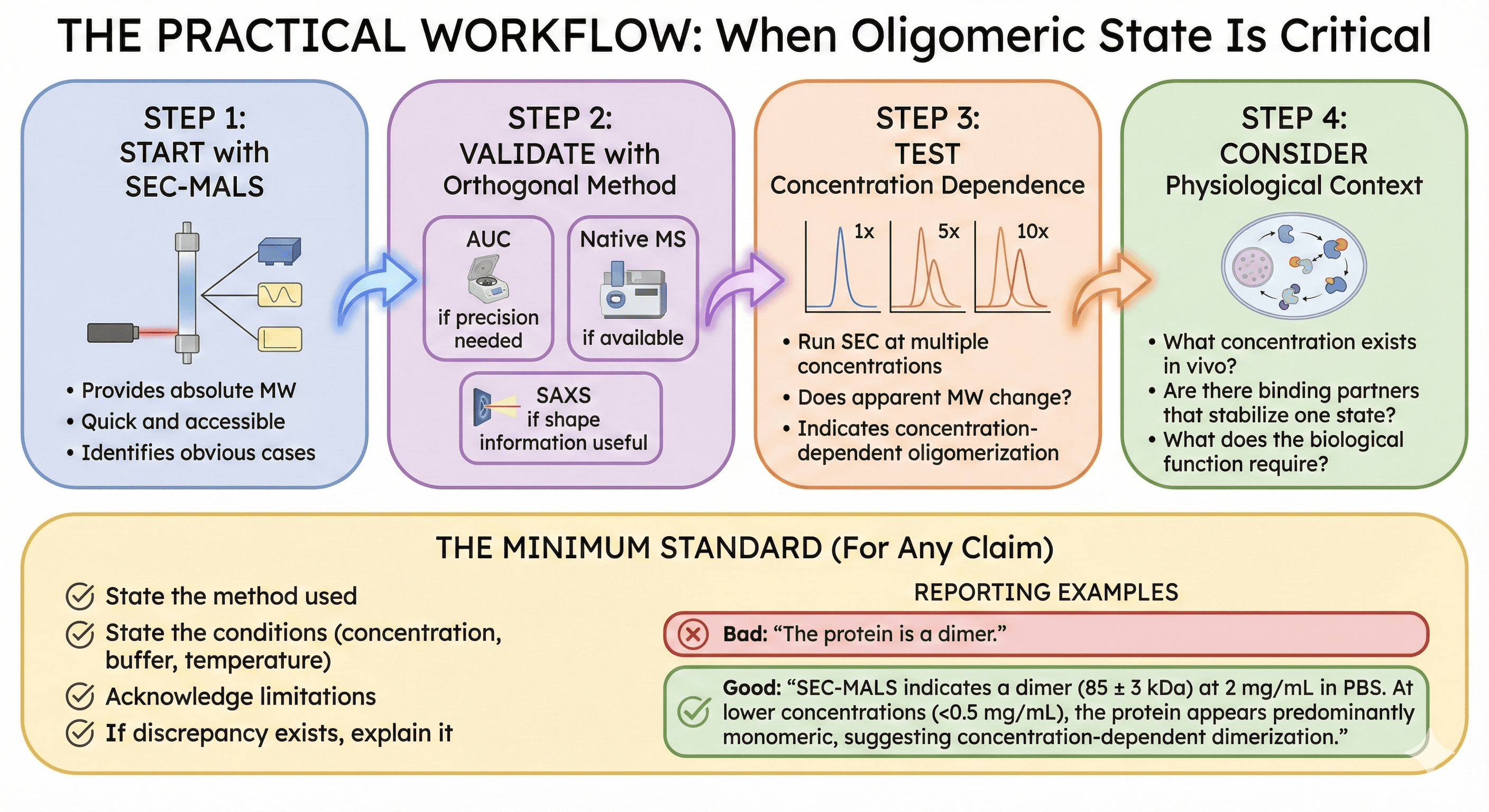

The Practical Workflow

When Oligomeric State Is Critical

Step 1: Start with SEC-MALS

Provides absolute MW

Quick and accessible

Identifies obvious cases

Step 2: Validate with orthogonal method

AUC if precision needed

Native MS if available

SAXS if shape information useful

Step 3: Test concentration dependence

Run SEC at multiple concentrations

Does apparent MW change?

This indicates concentration-dependent oligomerization

Step 4: Consider physiological context

What concentration exists in vivo?

Are there binding partners that stabilize one state?

What does the biological function require?

The Minimum Standard

For any claim about oligomeric state:

State the method used

State the conditions (concentration, buffer, temperature)

Acknowledge limitations

If discrepancy exists, explain it

Bad: "The protein is a dimer" Good: "SEC-MALS indicates a dimer (85 ± 3 kDa) at 2 mg/mL in PBS. At lower concentrations (<0.5 mg/mL), the protein appears predominantly monomeric, suggesting concentration-dependent dimerization."

Case Studies

Case 1: The Crystallographic Artifact

Protein: Metabolic enzyme from bacteria Crystal structure: Hexameric ring SEC: Monomer (45 kDa) SEC-MALS: Monomer (47 kDa) AUC: Monomer at all tested concentrations

Resolution: The hexamer was a crystallographic artifact. The six-fold symmetry of the space group promoted hexameric packing. Solution methods consistently showed monomer.

Consequence: Early drug design targeted the hexameric interface—which doesn't exist.

Case 2: The Concentration-Dependent Oligomer

Protein: Signaling protein Crystal structure: Dimer (solved at 20 mg/mL) SEC: Monomer (at 1 mg/mL) SEC-MALS at 10 mg/mL: Dimer

Resolution: Genuine concentration-dependent dimerization. Kd ≈ 5 mg/mL. Monomer and dimer both physiologically relevant at different cellular concentrations.

Consequence: Both forms studied separately; dimer has regulatory function.

Case 3: The Misleading SEC Peak

Protein: Transcription factor with long disordered N-terminus SEC: 120 kDa apparent (expected 60 kDa) Conclusion: "Must be a dimer" SEC-MALS: 62 kDa AUC: Monomer with f/f₀ = 1.8 (highly elongated)

Resolution: The disordered region increases hydrodynamic radius. The protein is a monomer that appears dimeric on calibrated SEC.

Consequence: Binding stoichiometry recalculated; mechanism revised.

Case 4: Multiple Conformations Hidden in Crystal

Protein: Metabolic enzyme (SDR family) Crystal structures: All show D2 symmetric tetramer Cryo-EM: ~50% symmetric tetramer, ~50% alternative conformations

Resolution: "The failure to observe conformations of this kind in the extensive crystallographic studies of SDR superfamily enzymes suggests that the requirement for stable packing in a regular lattice may have suppressed observation of these conformational states."

Consequence: Understanding of enzyme mechanism revised to include conformational heterogeneity.

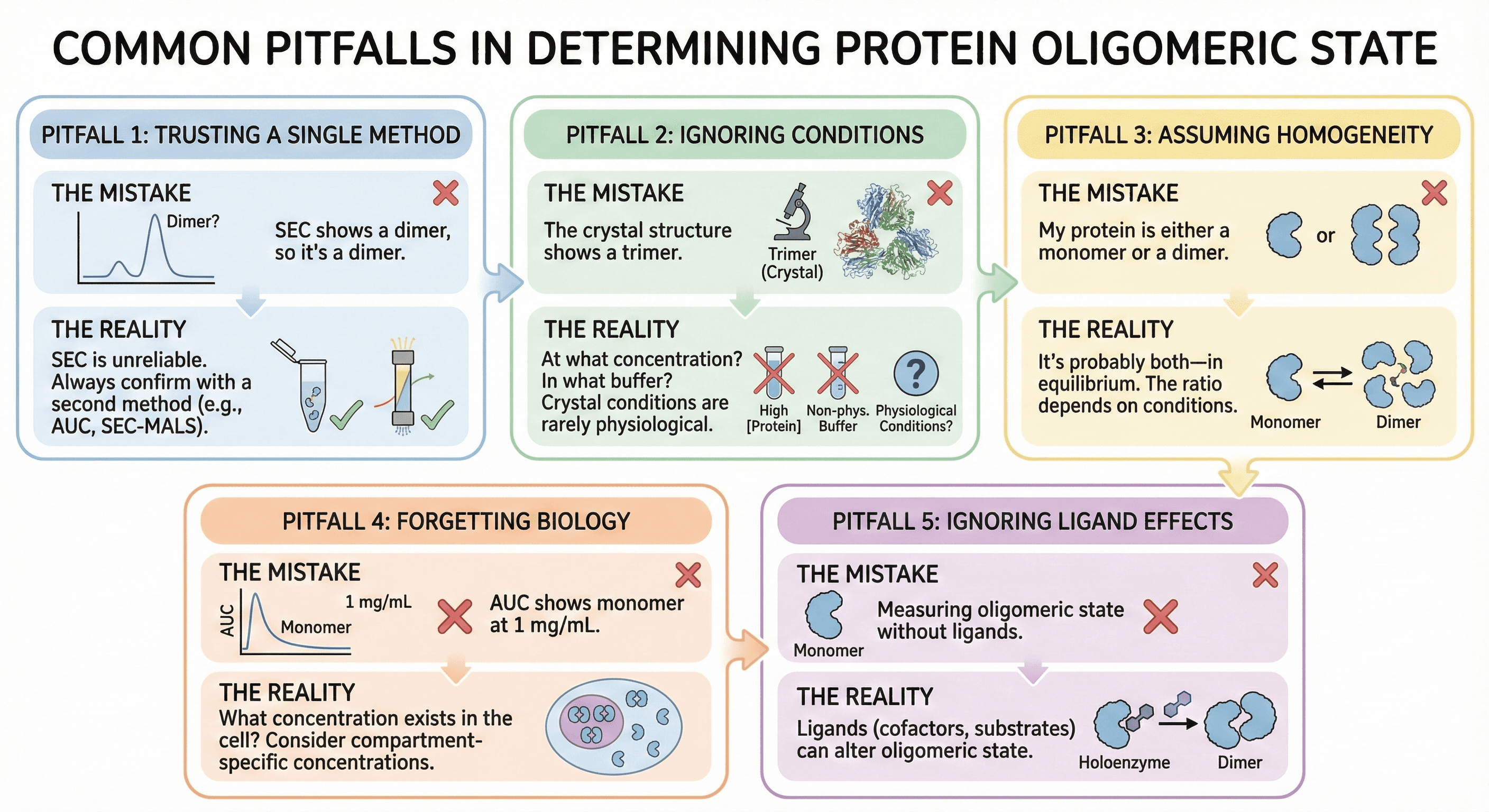

Common Pitfalls

Pitfall 1: Trusting a Single Method

The mistake: "SEC shows a dimer, so it's a dimer"

The reality: SEC is particularly unreliable for oligomeric state. Always confirm with a second method.

Pitfall 2: Ignoring Conditions

The mistake: "The crystal structure shows a trimer"

The reality: At what concentration? In what buffer? With what additives? Crystal conditions are rarely physiological.

Pitfall 3: Assuming Homogeneity

The mistake: "My protein is either a monomer or a dimer"

The reality: It's probably both—in equilibrium. The ratio depends on conditions.

Pitfall 4: Forgetting Biology

The mistake: "AUC shows monomer at 1 mg/mL"

The question: What concentration exists in the cell? If cellular concentration is 0.1 mg/mL, you've measured the relevant state. If it's 10 mg/mL (in some compartments), you may have missed the physiological oligomer.

Pitfall 5: Ignoring Ligand Effects

The mistake: Measuring oligomeric state without physiological ligands

The reality: Cofactors, substrates, and allosteric effectors can dramatically alter oligomeric state. Apoenzyme may be monomer; holoenzyme may be dimer.

The Interpretation Framework

Questions to Ask

What does the biology require?

Does function require multimerization?

Are there interface residues implicated in disease?

Do known regulatory mechanisms involve oligomerization?

Are the methods consistent?

If SEC and crystal agree: Probably correct

If methods disagree: More investigation needed

If concentration changes the answer: Concentration-dependent equilibrium

What about conservation?

Is the interface conserved across species?

Are interface residues under selection pressure?

Conserved interfaces are more likely biological

What about mutations?

Do mutations at the interface affect function?

Can you disrupt or stabilize the interface?

Mutagenesis provides functional validation

The Bottom Line

There's no simple answer to "what's the oligomeric state of my protein?" because:

Factor | Effect |

|---|---|

Concentration | Higher = more oligomer |

Buffer conditions | Can stabilize or destabilize interfaces |

Temperature | Affects equilibrium |

Ligands | Often shift equilibrium |

Method | Each has systematic biases |

The practical approach:

Use multiple methods

Test concentration dependence

Consider physiological relevance

Validate with mutagenesis if critical

The honest answer: "My protein exists as a monomer-dimer equilibrium with Kd of approximately X mg/mL, as determined by SEC-MALS and confirmed by AUC. At physiological concentrations, the predominant species is likely Y."

Structural Analysis for Oligomeric State

For researchers trying to understand their protein's quaternary structure, platforms like Orbion can provide initial guidance:

Interface analysis from predicted structures: Identify potential oligomerization surfaces

Conservation mapping: Highly conserved surface patches may indicate biological interfaces

Comparison to homologs: Do related proteins oligomerize?

Binding site prediction: Sites at putative interfaces suggest functional relevance

While computational analysis can't replace experimental validation, it can prioritize which interfaces to test and which methods to apply—helping you design the experiments that will resolve the discrepancy.

References

Krissinel E & Henrick K. (2007). Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. Journal of Molecular Biology, 372(3):774-797. PMC2271157

Frenkel D, et al. (2022). Protein quaternary structures in solution are a mixture of multiple forms. Chemical Science, 13:11687-11701. PMC9555727

Lebowitz J, et al. (2002). Modern analytical ultracentrifugation in protein science: A tutorial review. Protein Science, 11(9):2067-2079. PMC2373601

Schuck P. (2016). Analytical ultracentrifugation in structural biology. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 129:54-76. PMC5899701

Putnam CD, et al. (2007). X-ray solution scattering (SAXS) combined with crystallography and computation: defining accurate macromolecular structures, conformations and assemblies in solution. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics, 40(3):191-285. PMC5866936

Keifer DZ & Pierson EE. (2023). Native mass spectrometry: Recent progress and remaining challenges. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry, 16:475-495. PMC10700022

Akey DL, et al. (2022). Oligomeric interactions maintain active-site structure in a noncooperative enzyme family. Protein Science, 31(9):e4398. PMC9433937

Slabinski L, et al. (2007). The challenge of protein structure determination—lessons from structural genomics. Protein Science, 16(11):2472-2482.