Blog

The Tag Removal Problem: Why Your Protease Won't Cleave

Feb 4, 2026

The purification went perfectly. His-tag affinity, ion exchange, gel filtration—textbook chromatography. Now you just need to remove the tag before crystallization. You add TEV protease. Incubate overnight. Run the gel. Nothing happened. The band hasn't shifted. Your beautiful pure protein still has its tag, and your crystallization trials are on hold.

Tag removal should be straightforward: add protease, incubate, purify. In practice, it's one of the most frustrating steps in recombinant protein production.

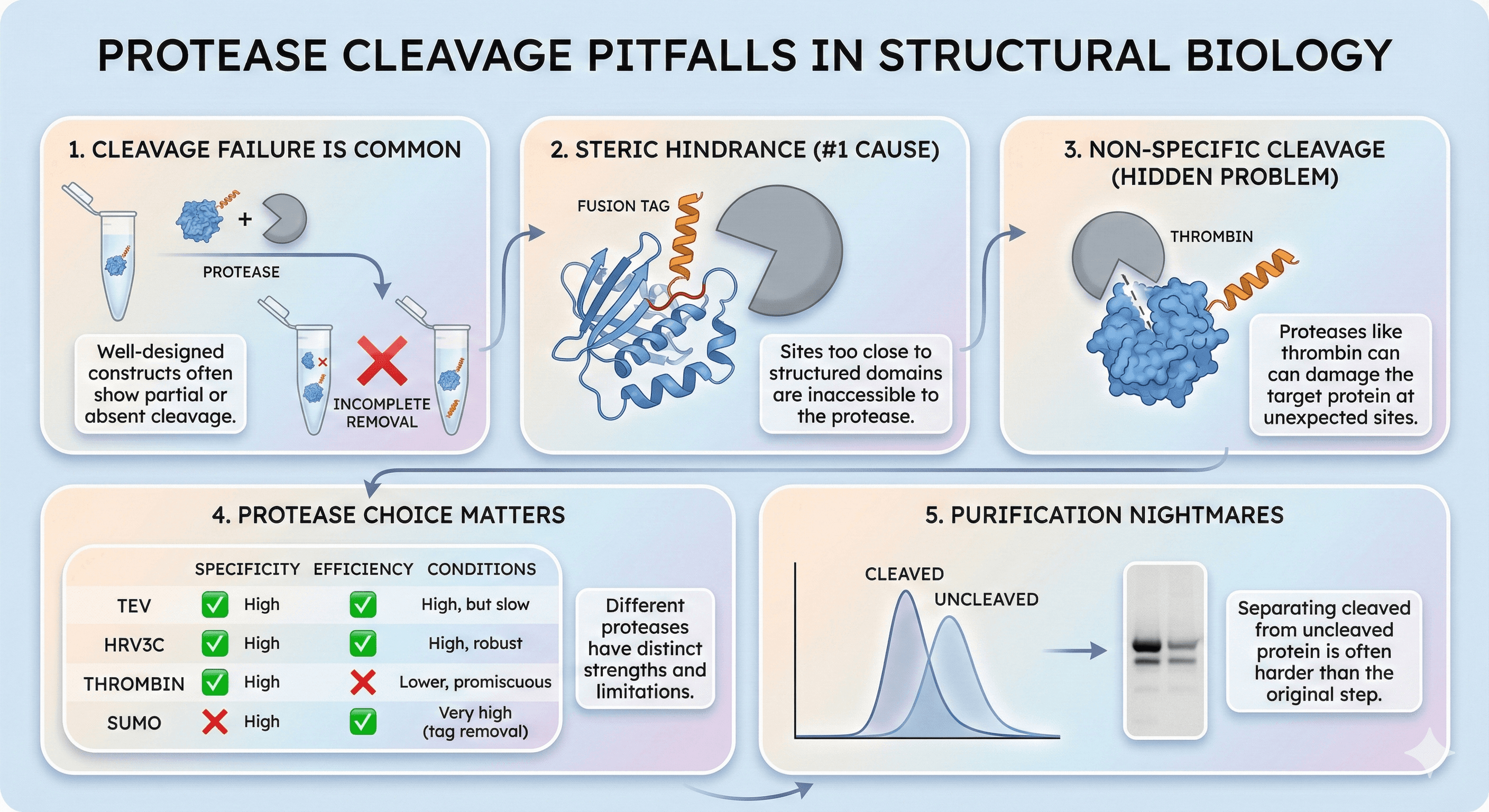

Key Takeaways

Protease cleavage failure is common: Even well-designed constructs frequently show incomplete or absent tag removal

Steric hindrance is the #1 cause: Cleavage sites too close to structured regions are inaccessible

Non-specific cleavage is a hidden problem: Proteases like thrombin can damage your protein at unexpected sites

Protease choice matters: TEV, HRV3C, thrombin, and SUMO protease have different strengths and limitations

Incomplete cleavage creates purification nightmares: Separating cleaved from uncleaved protein is often harder than the original purification

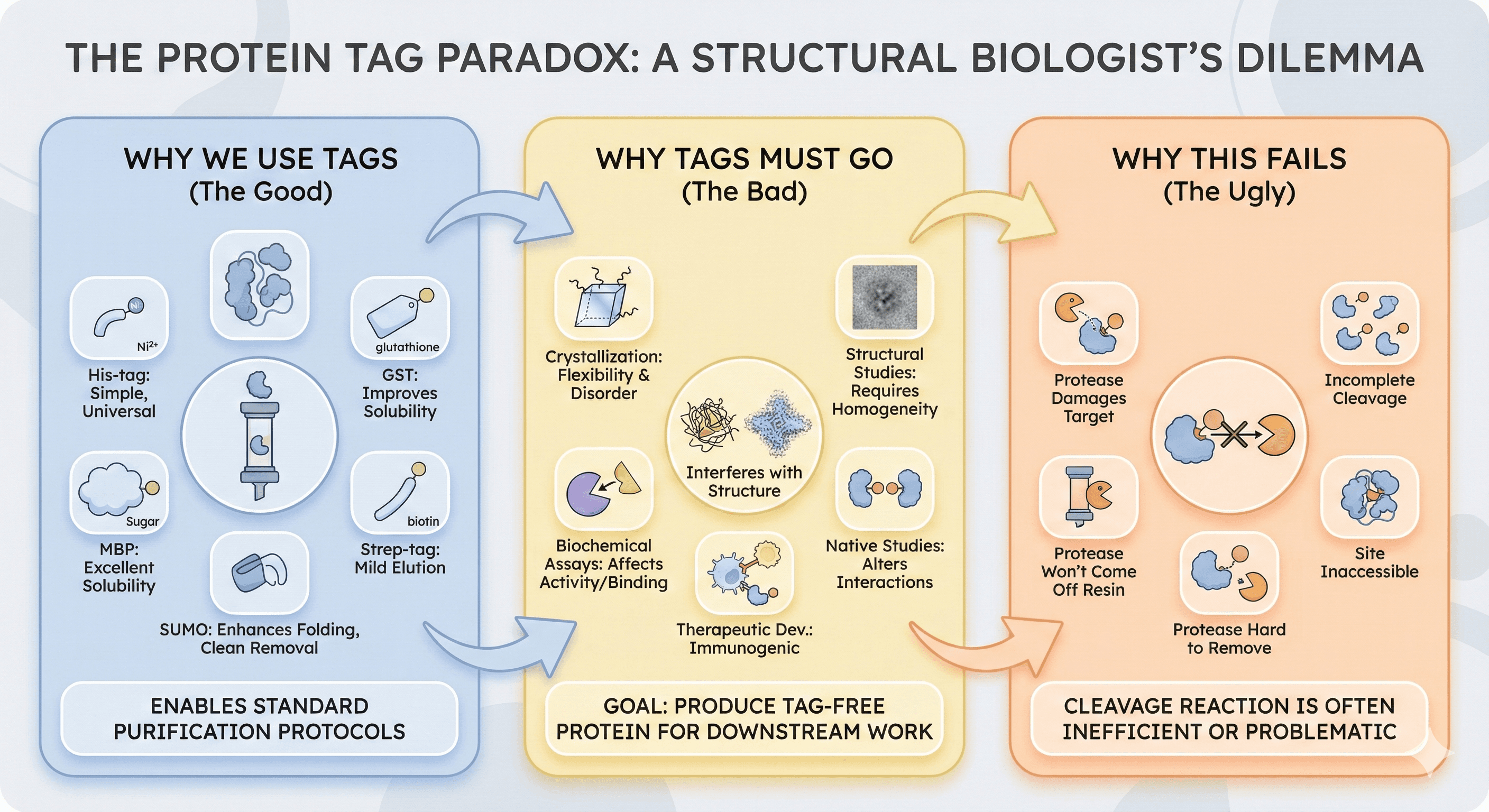

The Tag Removal Challenge

Why We Use Tags

Affinity tags revolutionized protein purification:

His-tag: Simple, universal, small

GST: Improves solubility, large but easy to remove

MBP: Excellent solubility enhancement

SUMO: Enhances folding, clean removal

Strep-tag: Mild elution conditions

Without tags, purification requires protein-specific method development. With tags, almost any protein can be purified with standard protocols.

Why Tags Must Go

Tags interfere with:

Crystallization: Tags introduce flexibility and disorder

Structural studies: Cryo-EM and X-ray require homogeneous samples

Biochemical assays: Tags can affect activity, binding, or localization

Therapeutic development: Non-native sequences are immunogenic

Native studies: Tags may alter oligomeric state or interactions

The goal: Capture the advantages of tagged expression, then produce tag-free protein for downstream work.

Why This Fails

The cleavage reaction seems simple:

In practice:

Protease can't access the cleavage site

Protease damages the target protein

Cleavage is incomplete

Protease won't come off the resin

Protease is as hard to remove as the tag

The Five Failure Modes

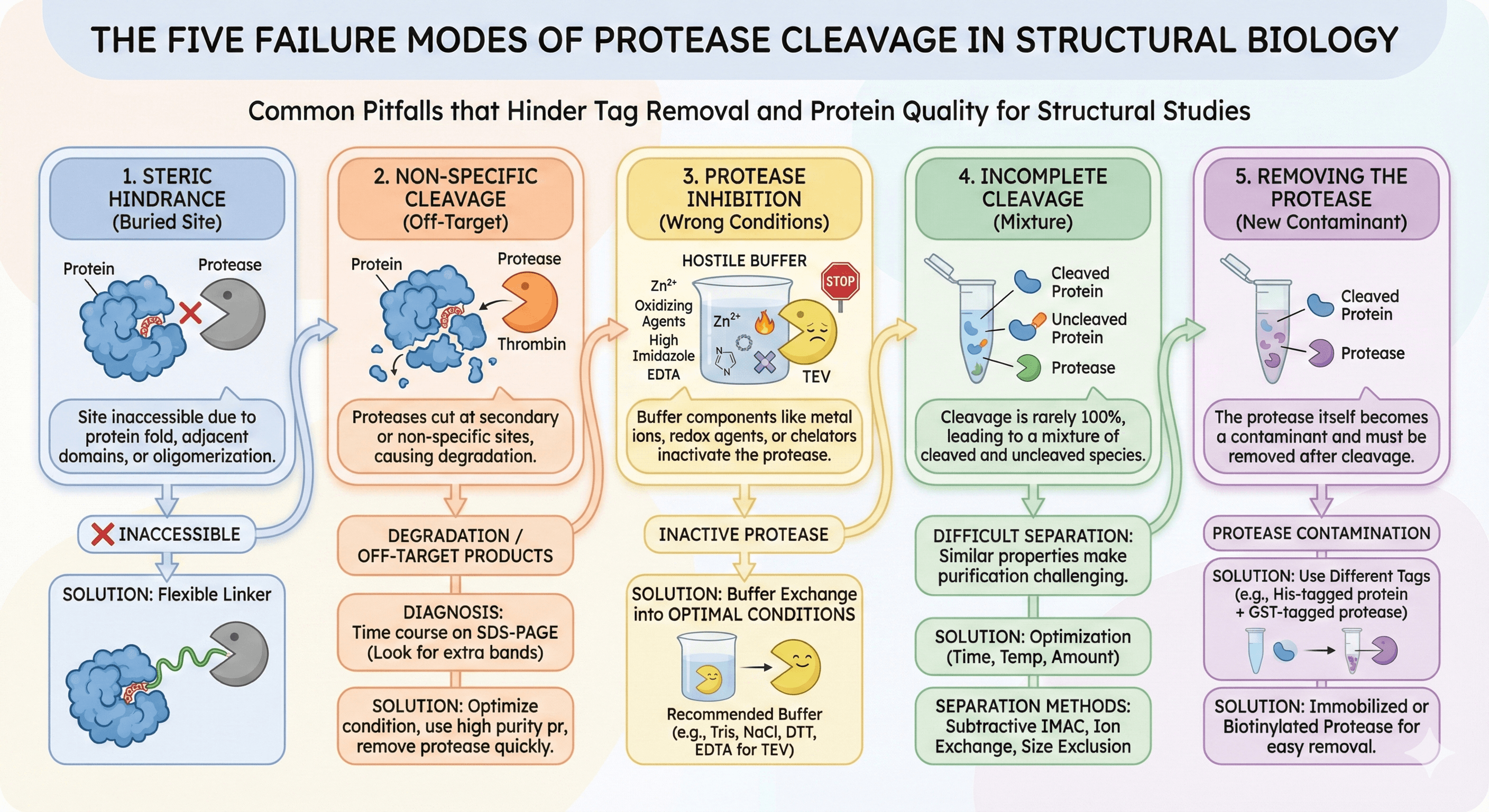

Failure 1: Steric Hindrance (The Cleavage Site Is Buried)

The problem: The protease needs to access and bind to the cleavage site. If the site is:

Too close to folded structure

Partially buried by the protein surface

Occluded by adjacent domains

Blocked by oligomerization

...the protease physically cannot reach it.

The evidence: Research on affinity tag removal has shown that "the inability of a protease to cleave a fusion protein may be caused by steric hindrance, which can be of several types. For example, the cleavage site may be too close to ordered structure in the target protein."

The problem is especially severe for oligomeric proteins. Even tags as small as polyhistidine can create steric problems when present on multiple subunits of a multimer.

The solution: Insert a flexible linker between the cleavage site and your protein. Studies have demonstrated that adding five glycine residues between the TEV protease recognition site and the target protein dramatically improved cleavage efficiency.

The design principle:

Failure 2: Non-Specific Cleavage (The Protease Damages Your Protein)

The problem: Proteases aren't perfectly specific. They have:

Primary site: The designed cleavage site

Secondary sites: Weaker recognition sequences elsewhere in your protein

Non-specific activity: Especially at high concentrations or long incubations

Thrombin is the worst offender: Research on thrombin-induced degradation found that "while thrombin and factor Xa are quite specific for cleavage at the inserted cleavage site, proteolysis can frequently occur at other site(s) in the protein of interest."

The problem is compounded by commercial thrombin preparations containing secondary protease activity from contaminating proteases.

TEV isn't immune: Recent studies have revealed unexpected TEV protease cleavage of recombinant human proteins at non-canonical sites. Using broader sequence specificity rules, researchers identified 456 human proteins that could be substrates for unwanted TEV cleavage.

The diagnostic approach:

Run time course: Remove samples at 1h, 2h, 4h, overnight

Analyze by SDS-PAGE

Look for: Extra bands (degradation products), decreasing band intensity (target destruction)

The solutions:

Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

Thrombin secondary cleavage | Use heparin-Sepharose to remove thrombin immediately after cleavage |

TEV off-target sites | Check sequence for canonical and non-canonical sites before design |

General over-digestion | Optimize protease:substrate ratio; less is often more |

Contaminating proteases | Use high-purity protease sources |

Failure 3: Protease Inhibition (Your Buffer Kills the Enzyme)

The problem: Proteases have specific requirements and sensitivities:

Protease | Inhibited By | Requires |

|---|---|---|

TEV | Zn²⁺ >5 mM, iodoacetamide, oxidizing conditions | DTT (1 mM), EDTA (0.5 mM) |

HRV3C | Oxidizing conditions | Reducing conditions |

Thrombin | EDTA, DTT, high imidazole | Ca²⁺, appropriate pH |

Factor Xa | EDTA, high salt | Ca²⁺ |

SUMO protease | Varies by source | Depends on specific enzyme |

Common mistakes:

IMAC elution buffer: High imidazole inhibits thrombin

Reducing agents: DTT reduces thrombin activity

Metal chelators: EDTA kills metalloproteases

Wrong pH: All proteases have pH optima

The solution:

Always buffer exchange into protease-compatible conditions before cleavage. The elution buffer from your affinity step is rarely optimal for proteolysis.

50 mM Tris pH 8.0

150 mM NaCl

1 mM DTT

0.5 mM EDTA

Temperature: 4°C or room temperature

Ratio: 1:100 (TEV:substrate by OD280)

Failure 4: Incomplete Cleavage (You Get a Mixture)

The problem: Even when cleavage works, it's rarely 100%. You end up with:

60-90% cleaved protein

10-40% uncleaved protein

Same affinity tag on both

Nearly identical size

Why this is a nightmare: If cleavage is 80% complete:

Re-running Ni-NTA removes 20% of your protein (the uncleaved fraction)

But 80% of your cleaved protein also binds (weakly) due to native histidines

You lose most of your cleaved protein trying to remove the uncleaved fraction

The numbers: Studies report that His-tag cleavage is often "far from 100% efficient," with many proteins showing substantial uncleaved fractions even after optimization.

Solutions for improving cleavage:

More protease: But watch for non-specific cleavage

Longer incubation: But protein may aggregate or degrade

Higher temperature: TEV is maximally active at 34°C, but your protein may not survive

Fresh protease: Old protease loses activity

Solutions for separating cleaved/uncleaved:

Method | Principle | Challenge |

|---|---|---|

Subtractive IMAC | Uncleaved binds, cleaved flows through | Cleaved often has weak binding too |

Ion exchange | Charge difference | Small tag = small charge difference |

Size exclusion | Size difference | Tag often too small to resolve |

Reverse IMAC | His-tag protease binds, both proteins flow through | Need His-tagged protease |

Failure 5: Removing the Protease (Now You Have a New Contaminant)

The problem: After cleavage, your sample contains:

Cleaved target protein

Uncleaved target protein

Free tag

Protease

If the protease has the same tag as your protein (common with His-tagged TEV), standard subtractive purification won't work—both bind or both flow through together.

The on-column cleavage trap: On-column cleavage (adding protease while protein is on the affinity resin) seems elegant but often fails because the tag-removal protease binds the resin, sterically limiting its proteolytic activity.

Solutions:

Use differently tagged protease:

His-tagged protein + GST-tagged TEV

Then: Ni-NTA (removes uncleaved protein) → Glutathione (removes TEV)

Use untagged protease:

Commercially available

Requires additional purification step to separate by size or charge

Use immobilized protease:

Protease covalently attached to resin

Cleavage in batch, then filter

Protease stays on resin

Use biotinylated protease:

Cleave in solution

Remove protease with streptavidin beads

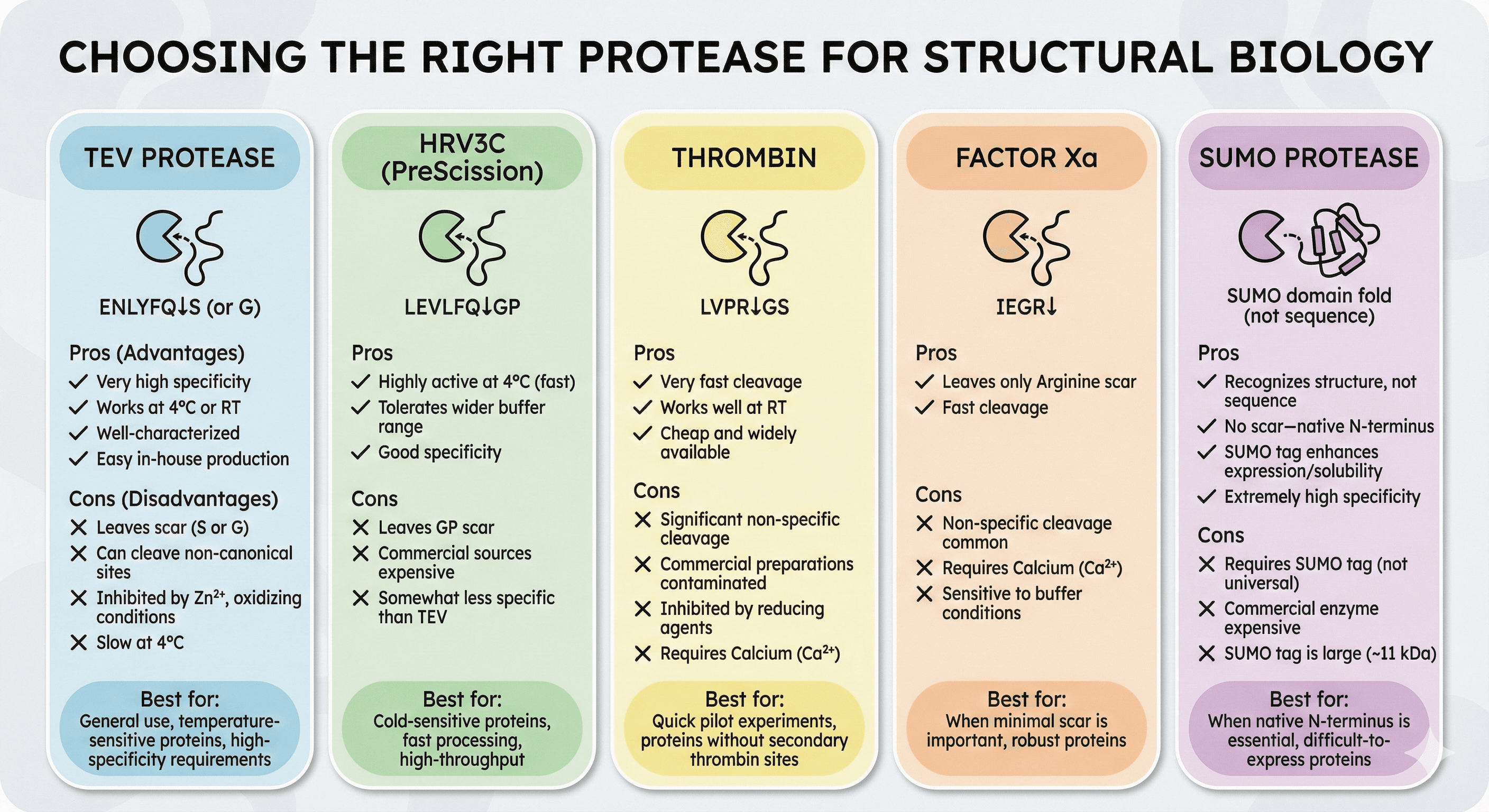

Choosing the Right Protease

TEV Protease

Recognition site: ENLYFQ↓S (or G)

Advantages:

Very high specificity

Works at 4°C (slowly) or room temperature (faster)

Well-characterized

Easy to produce in-house

Disadvantages:

Leaves scar (serine or glycine on target N-terminus)

Can cleave non-canonical sites in some proteins

Inhibited by zinc, oxidizing conditions

Slow at 4°C (overnight typical)

Best for: General use, temperature-sensitive proteins, high-specificity requirements

HRV3C (PreScission) Protease

Recognition site: LEVLFQ↓GP

Advantages:

Highly active at 4°C (minutes to hours)

Tolerates wider range of buffer additives than TEV

Good specificity

Disadvantages:

Leaves GP scar on target

Commercial sources can be expensive

Somewhat less specific than TEV

Best for: Cold-sensitive proteins, fast processing, high-throughput

Thrombin

Recognition site: LVPR↓GS

Advantages:

Very fast cleavage

Works well at room temperature

Cheap and widely available

Disadvantages:

Commercial preparations often contaminated

Inhibited by reducing agents

Requires calcium

Best for: Quick pilot experiments, proteins without secondary thrombin sites

Factor Xa

Recognition site: IEGR↓

Advantages:

Leaves only arginine attached to target

Fast cleavage

Disadvantages:

Non-specific cleavage common

Requires calcium

Sensitive to buffer conditions

Best for: When minimal scar is important, robust proteins

SUMO Protease

Recognition site: SUMO domain fold (not sequence)

Advantages:

Recognizes structure, not sequence

No scar—native N-terminus

SUMO tag enhances expression and solubility

Extremely high specificity

Disadvantages:

Requires SUMO tag (not universal)

Commercial enzyme expensive

SUMO tag is large (~11 kDa)

Best for: When native N-terminus is essential, difficult-to-express proteins

The Troubleshooting Decision Tree

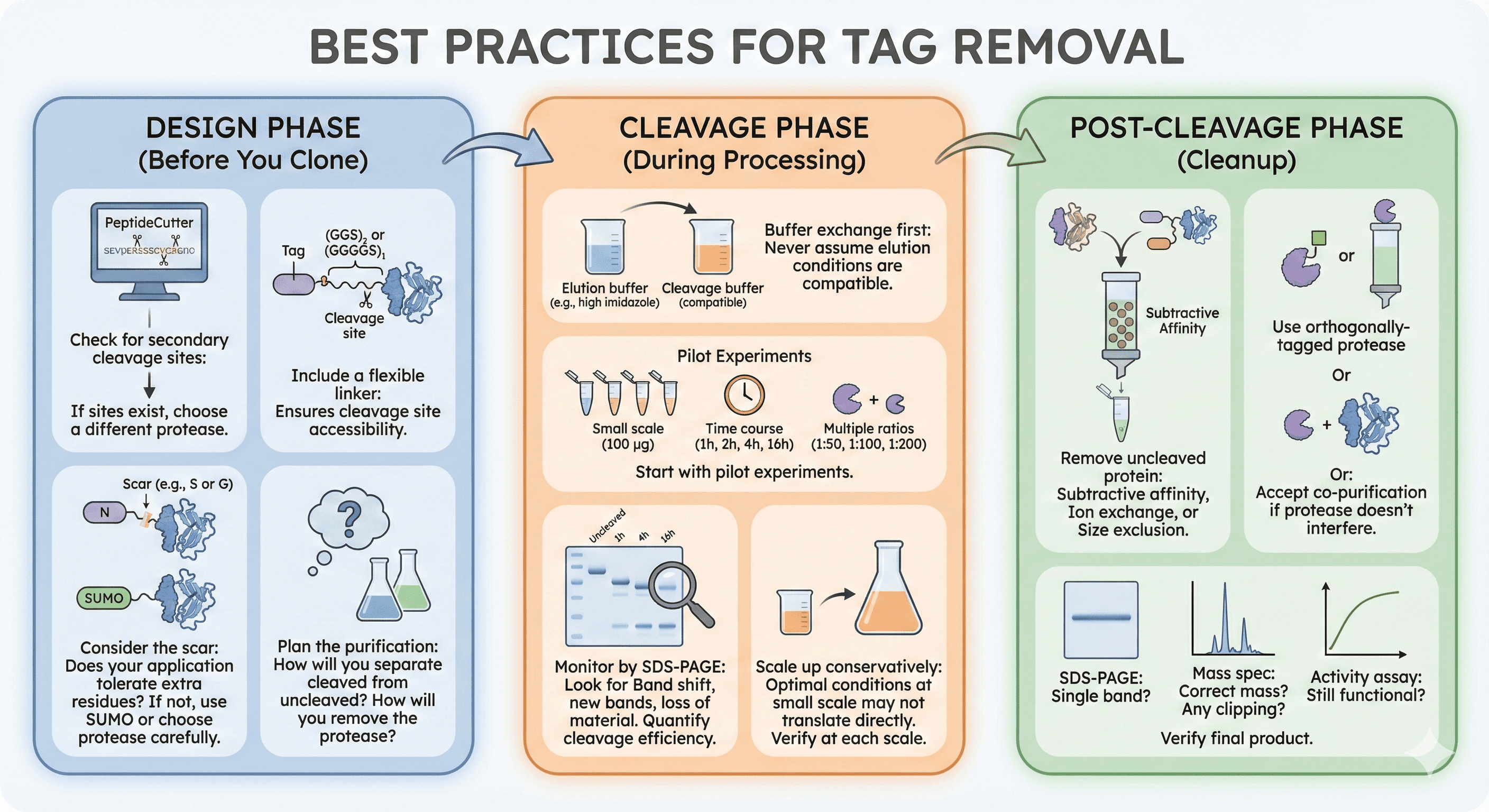

Best Practices for Tag Removal

Design Phase (Before You Clone)

Check for secondary cleavage sites:

Use PeptideCutter or similar tools

If sites exist, choose a different protease

Include a flexible linker:

(GGS)₂ or (GGGGS)₁ between tag and protein

Ensures cleavage site accessibility

Consider the scar:

Does your application tolerate extra residues at the N-terminus?

If not, use SUMO or choose protease carefully

Plan the purification:

How will you separate cleaved from uncleaved?

How will you remove the protease?

Cleavage Phase (During Processing)

Buffer exchange first:

Move from elution buffer to cleavage buffer

Never assume elution conditions are compatible

Start with pilot experiments:

Small scale (100 µg)

Time course (1h, 2h, 4h, 16h)

Multiple protease ratios (1:50, 1:100, 1:200)

Monitor by SDS-PAGE:

Look for: Band shift, new bands, loss of material

Quantify cleavage efficiency

Scale up conservatively:

Optimal conditions at small scale may not translate directly

Verify at each scale

Post-Cleavage Phase (Cleanup)

Remove uncleaved protein:

Subtractive affinity (if cleaved protein doesn't bind)

Ion exchange (if charge difference sufficient)

Size exclusion (if size difference sufficient)

Remove protease:

Use orthogonally-tagged protease

Or: Accept co-purification if protease doesn't interfere

Verify final product:

SDS-PAGE: Single band?

Mass spec: Correct mass? Any clipping?

Activity assay: Still functional?

Case Studies

Case 1: TEV Won't Cut

Protein: 45 kDa enzyme Construct: His6-TEV site-Target Problem: No cleavage after 24 hours with excess TEV

Diagnosis:

Crystal structure of homolog showed N-terminus buried in a groove

TEV site was inaccessible to protease

Solution:

Redesigned: His6-(GGGGS)₂-TEV site-(GGGGS)₂-Target

Cleavage now complete in 4 hours

Case 2: Thrombin Destroys the Protein

Protein: 30 kDa signaling domain Construct: His6-Thrombin site-Target Problem: Multiple bands after cleavage; activity lost

Diagnosis:

Target protein contained internal thrombin-like site

Both sites cleaved, fragmenting the protein

Solution:

Switched to TEV protease

No internal TEV sites present

Clean cleavage, full activity retained

Case 3: Can't Separate Cleaved from Uncleaved

Protein: 25 kDa structural protein Construct: His6-TEV site-Target Cleavage: 75% complete (couldn't improve further)

Problem: Cleaved protein has native His-rich region, binds Ni-NTA

Diagnosis:

Subtractive purification impossible

Both species bind column

Solution:

Switched to Strep-tag

StrepTactin binding is tag-specific

Cleaved protein flows through cleanly

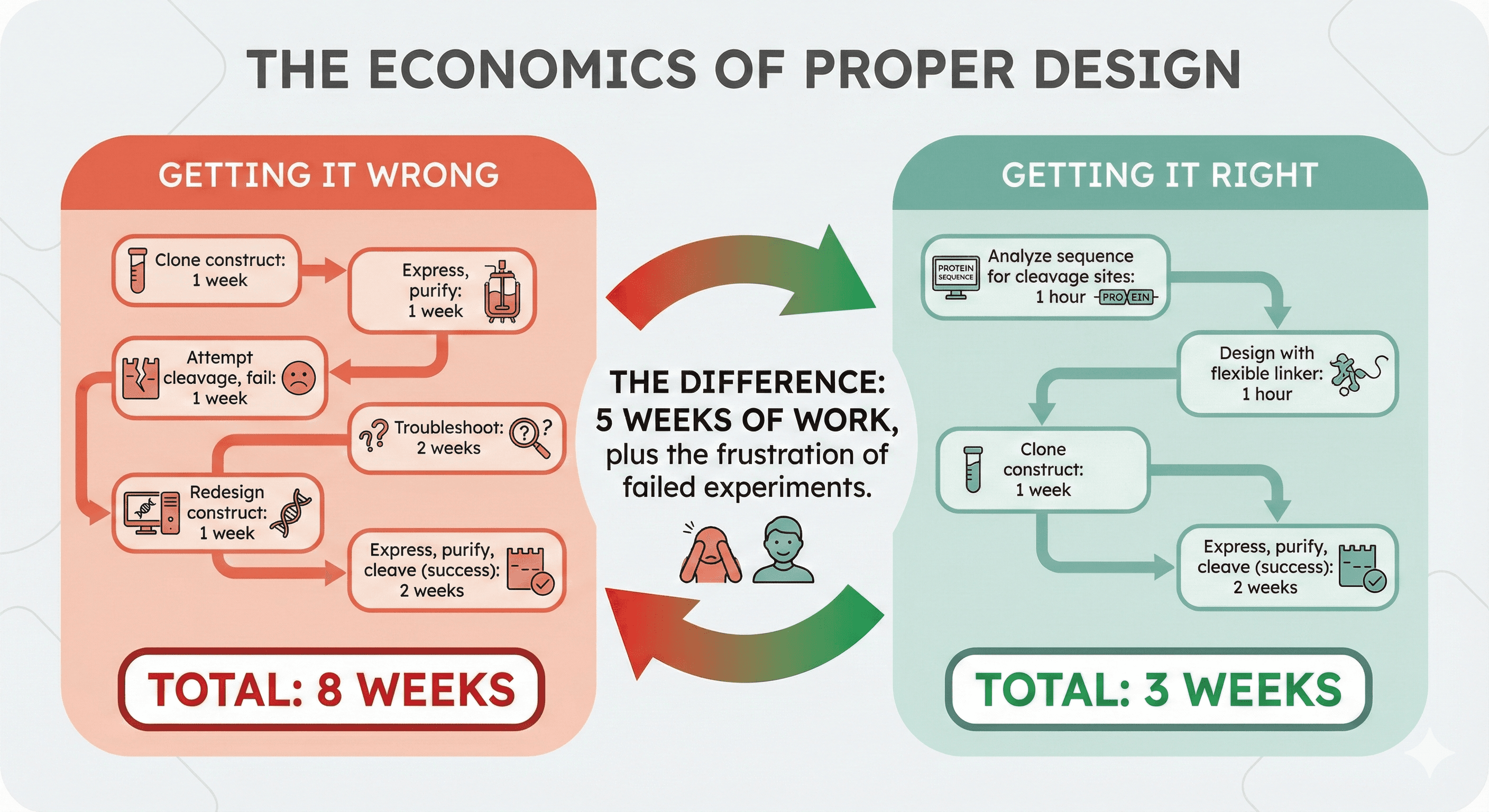

The Economics of Proper Design

Getting It Wrong

Clone construct: 1 week

Express, purify: 1 week

Attempt cleavage, fail: 1 week

Troubleshoot: 2 weeks

Redesign construct: 1 week

Express, purify, cleave (success): 2 weeks

Total: 8 weeks

Getting It Right

Analyze sequence for cleavage sites: 1 hour

Design with flexible linker: 1 hour

Clone construct: 1 week

Express, purify, cleave (success): 2 weeks

Total: 3 weeks

The difference: 5 weeks of work, plus the frustration of failed experiments.

The Bottom Line

Tag removal failure has predictable causes:

Cause | Prevention |

|---|---|

Steric hindrance | Design with flexible linkers |

Wrong buffer | Exchange before cleavage |

Non-specific cleavage | Check sequence, optimize conditions |

Incomplete cleavage | Pilot experiments, optimization |

Protease contamination | Plan removal strategy before starting |

The most common mistake is assuming cleavage will work without optimization. Every protein is different. What works for one construct may fail completely for another.

Design for success: check sequences, include linkers, plan your purification, and always run pilot experiments before committing to large-scale cleavage.

Construct Design Considerations

For researchers designing expression constructs, platforms like Orbion can help identify potential problems before cloning:

Secondary cleavage site detection: Identify sequences that match protease recognition patterns

Terminus accessibility analysis: Predict whether N- and C-termini are accessible or structured

PTM site mapping: Ensure cleavage sites don't overlap with essential modifications

Disorder prediction: Identify flexible regions suitable for tag placement

Good construct design prevents most tag removal problems—and good design starts with understanding your protein's structure and sequence features before you order the first oligonucleotide.

References

Waugh DS. (2011). An overview of enzymatic reagents for the removal of affinity tags. Protein Expression and Purification, 80(2):283-293. PMC3195948

Feehan RP & Bhattacharya S. (2024). Unexpected tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage of recombinant human proteins. Protein Expression and Purification, 220:106498. PMC11129917

Peti W & Page R. (2007). Strategies to maximize heterologous protein expression in Escherichia coli with minimal cost. Protein Expression and Purification, 51(1):1-10.

Ahuja S, et al. (2008). A method for the prevention of thrombin-induced degradation of recombinant proteins. Analytical Biochemistry, 382(1):67-69. PMC2614318

Kapust RB & Waugh DS. (2017). Removal of affinity tags with TEV protease. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1586:221-241. PMC7974378

Kronqvist N, et al. (2020). NT*-HRV3CP: An optimized construct of human rhinovirus 14 3C protease for high-yield expression and fast affinity-tag cleavage. Journal of Biotechnology, 323:109-117. ScienceDirect

Sigma-Aldrich. (2024). Tag removal proteases for recombinant protein purification. Technical Document. Link