Blog

Why Your Protein Loses Activity After Purification (Even Though It's Pure)

Feb 2, 2026

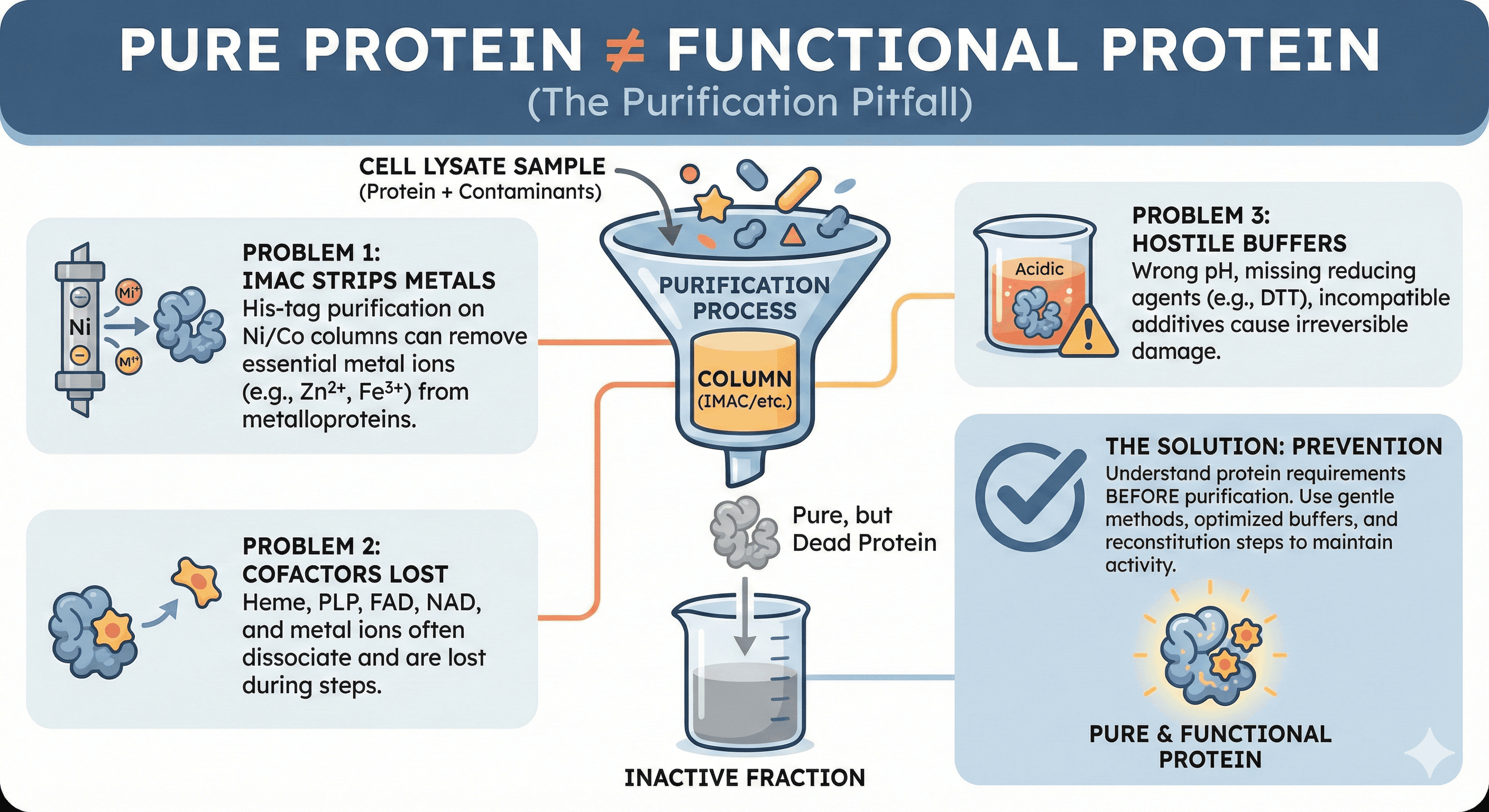

The chromatogram looked perfect. You ran the gel—single band at the expected molecular weight. The mass spec confirmed the identity. Your protein is >95% pure. Then you ran the activity assay. Nothing. The enzyme that was robustly active in crude lysate is now completely dead.

You didn't lose purity. You lost function. And the purification itself was the culprit.

Key Takeaways

Pure protein is not the same as functional protein: Purification removes more than just contaminants—it can strip essential cofactors, metal ions, and binding partners

IMAC is particularly problematic: His-tag purification on nickel/cobalt columns can strip metal ions from metalloproteins

Cofactors don't survive purification: Heme, PLP, FAD, NAD, and metal ions often need reconstitution

Buffer composition matters enormously: Wrong pH, missing reducing agents, or incompatible additives cause irreversible damage

Activity loss is often preventable: Understanding your protein's requirements before purification is the key

The Purity-Activity Paradox

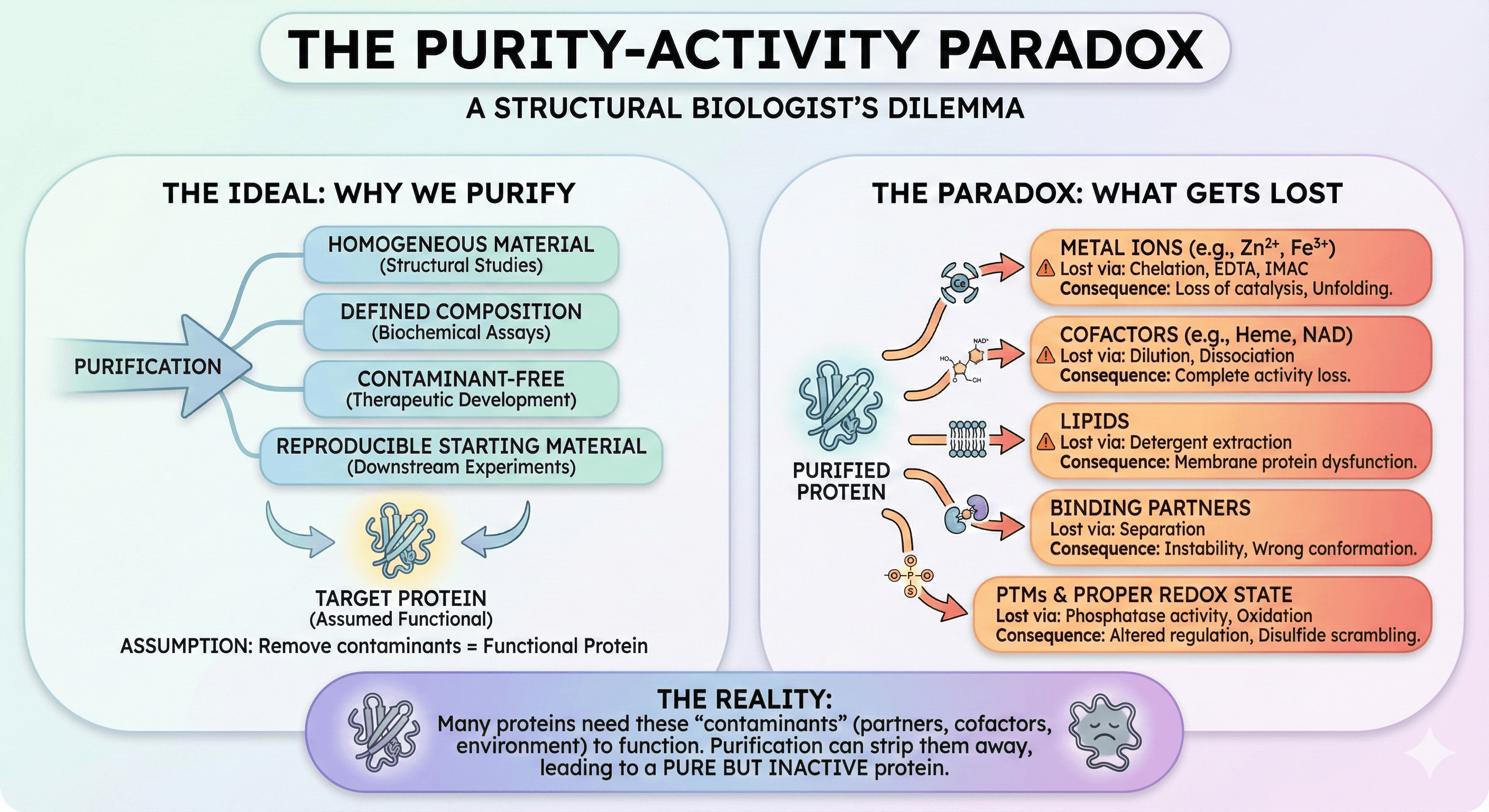

Why Do We Purify Proteins?

Purification is supposed to give us:

Homogeneous material for structural studies

Defined composition for biochemical assays

Contaminant-free samples for therapeutic development

Reproducible starting material for downstream experiments

The assumption: If we remove everything except our target protein, we'll have functional protein.

The reality: Many proteins need "contaminants" to function.

What Gets Lost

During purification, your protein can lose:

Component | How It's Lost | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

Metal ions | Chelation, EDTA, IMAC | Loss of catalysis, unfolding |

Cofactors | Dilution, dissociation | Complete activity loss |

Lipids | Detergent extraction | Membrane protein dysfunction |

Binding partners | Separation | Instability, wrong conformation |

PTMs | Phosphatase activity | Altered regulation |

Proper redox state | Oxidation | Disulfide scrambling |

The Six Ways Activity Dies During Purification

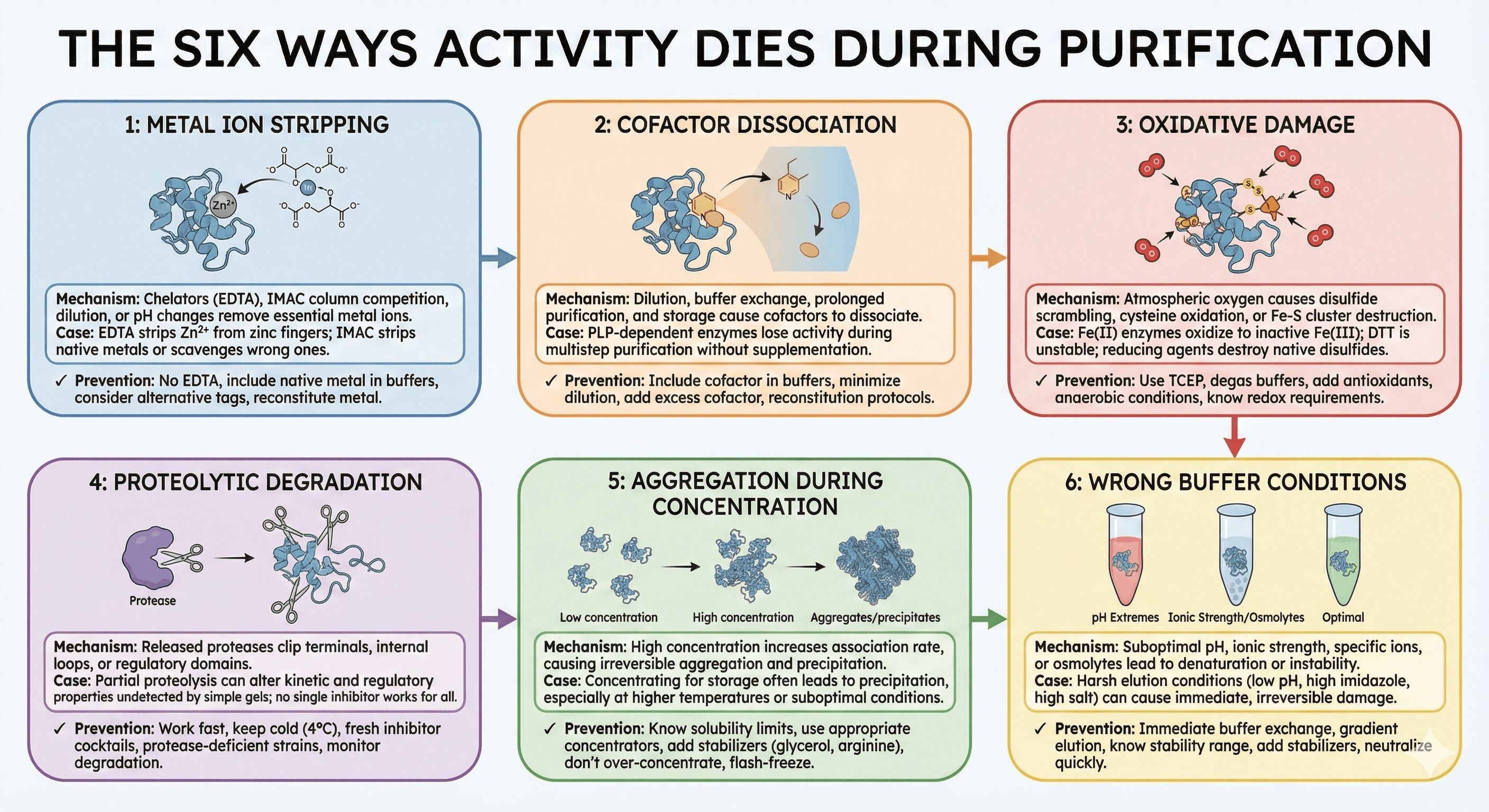

Problem 1: Metal Ion Stripping

The mechanism:

Many enzymes require metal ions for catalysis:

Zinc: Metalloproteases, carbonic anhydrase, zinc fingers

Iron: Cytochromes, iron-sulfur proteins, non-heme iron enzymes

Magnesium: Kinases, ATPases, polymerases

Copper: Oxidases, electron transport proteins

Manganese: Arginase, superoxide dismutase

During purification, metal ions are stripped by:

EDTA in buffers (even trace amounts)

Competition with IMAC column metals

Dilution below binding threshold

pH changes that alter coordination

The IMAC problem:

Research has shown that metalloproteins are particularly problematic for IMAC purification because they can scavenge metal ions from the column or have their native metals stripped. Both M-PMV and HIV-1 proteins were found to scavenge Zn²⁺ and Ni²⁺ ions from charged IMAC column matrix during elution—meaning your protein may come off the column with the wrong metal.

Case study: Zinc finger proteins

Studies on zinc-binding transcriptional regulators have demonstrated that EDTA, commonly present at 0.1-5 mM in purification buffers, can completely sequester Zn²⁺ from zinc finger proteins. The log formation constant for Zn-EDTA is 13.3, while zinc finger domains bind with constants of only 10⁷ to 10¹¹—meaning EDTA wins the competition for zinc almost every time.

Worse, some zinc-binding domains are irreversibly denatured after zinc removal and cannot refold even when zinc is added back.

Prevention:

Never use EDTA in buffers for metalloproteins

Include the native metal ion in all purification buffers

Consider alternative affinity tags (Strep-tag, FLAG) instead of His-tag

If using IMAC, reconstitute metal after elution

Problem 2: Cofactor Dissociation

The mechanism:

Many enzymes have non-covalently bound cofactors:

Heme: Cytochromes P450, peroxidases, globins

FAD/FMN: Oxidoreductases, monooxygenases

PLP (pyridoxal phosphate): Transaminases, decarboxylases

NAD/NADP: Dehydrogenases

Biotin: Carboxylases

Thiamine pyrophosphate: Decarboxylases, transketolases

Cofactors dissociate during:

Dilution (reduces effective concentration)

Buffer exchange (washes away free cofactor)

Prolonged purification (equilibrium shifts)

Storage (slow dissociation over time)

The heme problem:

Research on recombinant heme proteins has shown that production in E. coli is often limited by the host's heme biosynthesis, resulting in only partially assembled holo-heme protein. Even proteins that express with heme can lose it during purification.

In vitro reconstitution studies found that purified cytochrome c synthases contain only ~10% occupied heme; a special "heme-loading" protocol was needed to increase this to ~30%.

Case study: PLP-dependent enzymes

A transaminase purified without PLP supplementation:

Crude lysate: 100% activity (cellular PLP present)

After Ni-NTA: 60% activity (PLP diluting out)

After size exclusion: 25% activity (more dilution)

After concentration: 10% activity (most PLP lost)

The same purification with 100 μM PLP in all buffers: 95% activity retention.

Prevention:

Include cofactor in all purification buffers

Minimize dilution during purification

Add excess cofactor before storage

For heme proteins, consider reconstitution protocols

Problem 3: Oxidative Damage

The mechanism: Many proteins contain:

Free cysteines: Subject to oxidation

Iron-sulfur clusters: Oxygen-sensitive

Reduced cofactors: Air-oxidizable

Methionine residues: Oxidize to sulfoxide

Atmospheric oxygen causes:

Disulfide bond formation (aggregation, wrong structure)

Cysteine sulfenic acid formation (activity loss)

Iron-sulfur cluster destruction

Cofactor oxidation

The cysteine problem: DTT and other reducing agents are essential for proteins with free cysteines. Without them, artefactual disulfide bonds form, leading to aggregation and misfolding. However, DTT itself is unstable—its half-life is only 1.4 hours at pH 8.5 and 20°C.

For proteins that require native disulfide bonds, the situation is reversed: reducing agents will destroy the correct disulfide bonds, causing unfolding and activity loss.

Case study: Non-heme iron enzymes

Non-heme iron (II) enzymes face a particular challenge: the iron readily oxidizes to iron (III), which is catalytically inactive. A significant fraction of purified protein often contains no iron at all, requiring reconstitution after purification.

Prevention:

Use TCEP instead of DTT (more stable, compatible with IMAC)

Degas buffers for oxygen-sensitive proteins

Include antioxidants (ascorbate, reduced glutathione) where appropriate

Purify in anaerobic chamber for extreme cases

Know whether your protein needs reducing or oxidizing conditions

Problem 4: Proteolytic Degradation

The mechanism: Cell lysis releases proteases from their normal compartmentalization. These proteases can:

Clip terminal regions (removing tags or functional domains)

Cleave internal loops (fragmenting the protein)

Remove regulatory domains (altering activity)

Research on proteolysis during purification emphasizes that the problem is insidious: partial proteolysis may not be visible on a gel but can cause "striking changes to kinetic and regulatory properties."

The inhibitor challenge: No single protease inhibitor works against all proteases. Standard cocktails contain:

AEBSF/PMSF: Serine proteases

E-64: Cysteine proteases

Pepstatin: Aspartic proteases

Bestatin: Aminopeptidases

EDTA: Metalloproteases

But EDTA creates its own problems (see Problem 1), and PMSF has a half-life of only ~30 minutes in aqueous solution.

Prevention:

Work fast—minimize time between lysis and first chromatography

Keep everything cold (4°C)

Use fresh protease inhibitor cocktails

Consider protease-deficient expression strains

Monitor for degradation products on gels

Problem 5: Aggregation During Concentration

The mechanism: After purification, proteins are often concentrated for storage or downstream applications. During concentration:

Local protein concentration increases dramatically

Hydrophobic patches find each other

Aggregation-prone intermediates form

Once aggregated, protein is often irreversibly lost

Studies on protein aggregation show that the problem worsens with:

Higher target concentration

Higher temperature

Suboptimal pH

Ionic strength extremes

Surface adsorption in concentrators

The concentration trap: Protein is soluble at 1 mg/mL during purification. You concentrate to 10 mg/mL for storage. Overnight at 4°C, white precipitate appears. The protein is lost.

This happens because:

Many proteins have concentration-dependent aggregation thresholds

Concentration increases the rate of all association events, including unwanted ones

Impurities or misfolded species nucleate aggregation

Prevention:

Know your protein's solubility limit before concentrating

Use appropriate concentrator MWCO (not too close to protein MW)

Add stabilizers (glycerol, arginine, trehalose)

Don't over-concentrate—leave margin below solubility limit

Flash-freeze immediately after concentration

Problem 6: Wrong Buffer Conditions

The mechanism: Proteins have optimal conditions for stability and activity:

pH: Most enzymes have narrow pH optima

Ionic strength: Too low = aggregation; too high = denaturation

Specific ions: Some require specific cations/anions

Osmolytes: Some need stabilizers

Temperature: Some are cold-sensitive or heat-labile

During purification, conditions change multiple times: Lysis buffer → Binding buffer → Wash buffer → Elution buffer → Storage buffer. Each transition is an opportunity for damage.

Case study: The elution step

Many elution conditions are harsh:

Low pH (4.0) for Protein A

High imidazole (500 mM) for IMAC

High salt for ion exchange

Organic solvents for hydrophobic interaction

The protein may not survive these conditions, even briefly.

Prevention:

Buffer exchange immediately after elution

Use gradient elution where possible (less harsh)

Know your protein's pH stability range

Include stabilizers in elution buffers

Neutralize immediately after low-pH elution

The Diagnostic Workflow

When Activity Is Lost, Ask These Questions

Step 1: At which step did activity disappear?

Run activity assays at each purification stage:

Lysate

Post-affinity

Post-ion exchange

Post-gel filtration

After concentration

After storage

The step where activity drops is where the damage occurs.

Step 2: What changed at that step?

Step | Common Culprits |

|---|---|

Lysis | Proteolysis, oxidation, metal loss |

Affinity (IMAC) | Metal stripping, wrong metal incorporation |

Ion exchange | pH stress, ionic strength shock |

Gel filtration | Dilution of cofactors, partner loss |

Concentration | Aggregation, surface adsorption |

Storage | Oxidation, freeze-thaw damage |

Step 3: Can activity be rescued?

Try reconstitution:

Add back suspected metal ion

Add cofactor in excess

Add reducing agent

Add suspected binding partner

Change to optimal buffer

If activity is rescued, you've identified the problem.

Prevention Strategies

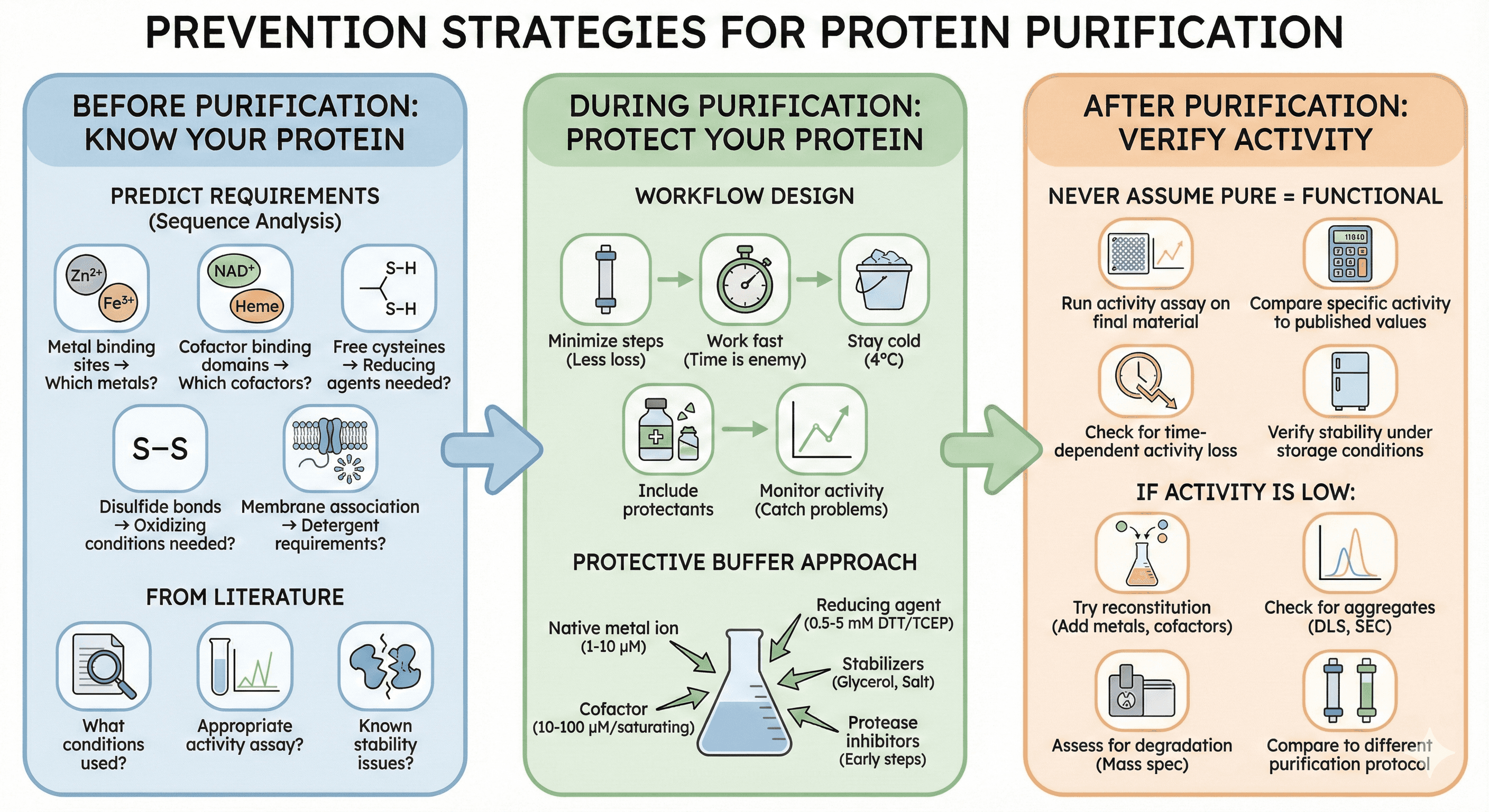

Before Purification: Know Your Protein

Predict requirements: From sequence analysis:

Metal binding sites → Which metals?

Cofactor binding domains → Which cofactors?

Free cysteines → Reducing agents needed?

Disulfide bonds → Oxidizing conditions needed?

Membrane association → Detergent requirements?

From literature:

What conditions have others used?

What activity assay is appropriate?

What are known stability issues?

During Purification: Protect Your Protein

Design the workflow with function in mind:

Minimize steps: Every column is an opportunity for loss

Work fast: Time is the enemy for unstable proteins

Stay cold: 4°C slows most degradation processes

Include protectants: Metals, cofactors, reducing agents

Monitor activity: Not just purity—catch problems early

The protective buffer approach: Instead of standard purification buffers, design buffers that include:

The native metal ion (1-10 μM range)

The cofactor (10-100 μM range, or saturating)

Appropriate reducing agent (0.5-5 mM DTT or TCEP)

Stabilizers (5-10% glycerol, 100-500 mM salt)

Protease inhibitors (during early steps)

After Purification: Verify Activity

Never assume pure means functional:

Run activity assay on final material

Compare specific activity to published values

Check for time-dependent activity loss

Verify activity is stable under storage conditions

If activity is low:

Try reconstitution (add metals, cofactors)

Check for aggregates (DLS, SEC)

Assess for degradation (mass spec)

Compare to different purification protocol

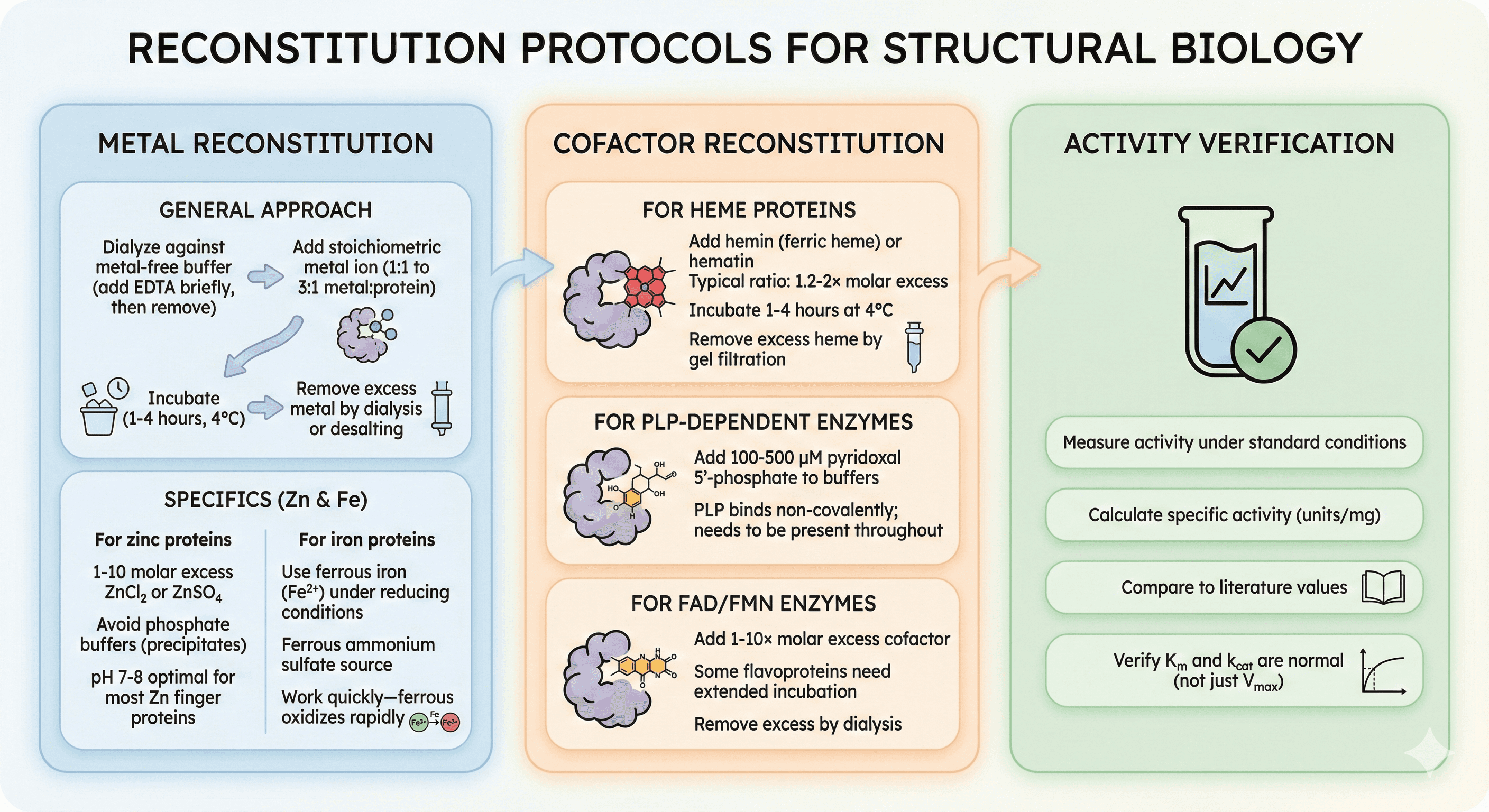

Reconstitution Protocols

Metal Reconstitution

General approach:

Dialyze protein against metal-free buffer (add EDTA briefly, then remove)

Add stoichiometric metal ion (1:1 to 3:1 metal:protein)

Incubate (1-4 hours, 4°C)

Remove excess metal by dialysis or desalting

For zinc proteins:

1-10 molar excess ZnCl₂ or ZnSO₄

Avoid phosphate buffers (zinc phosphate precipitates)

pH 7-8 optimal for most zinc finger proteins

For iron proteins:

Use ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) under reducing conditions

Ferrous ammonium sulfate is common source

Work quickly—ferrous oxidizes rapidly

Cofactor Reconstitution

For heme proteins:

Add hemin (ferric heme) or hematin

Typical ratio: 1.2-2× molar excess

Incubate 1-4 hours at 4°C

Remove excess heme by gel filtration

For PLP-dependent enzymes:

Add 100-500 μM pyridoxal 5'-phosphate to buffers

PLP binds non-covalently; needs to be present throughout

For FAD/FMN enzymes:

Add 1-10× molar excess cofactor

Some flavoproteins need extended incubation

Remove excess by dialysis

Activity Verification

After reconstitution:

Measure activity under standard conditions

Calculate specific activity (units/mg)

Compare to literature values

Verify Km and kcat are normal (not just Vmax)

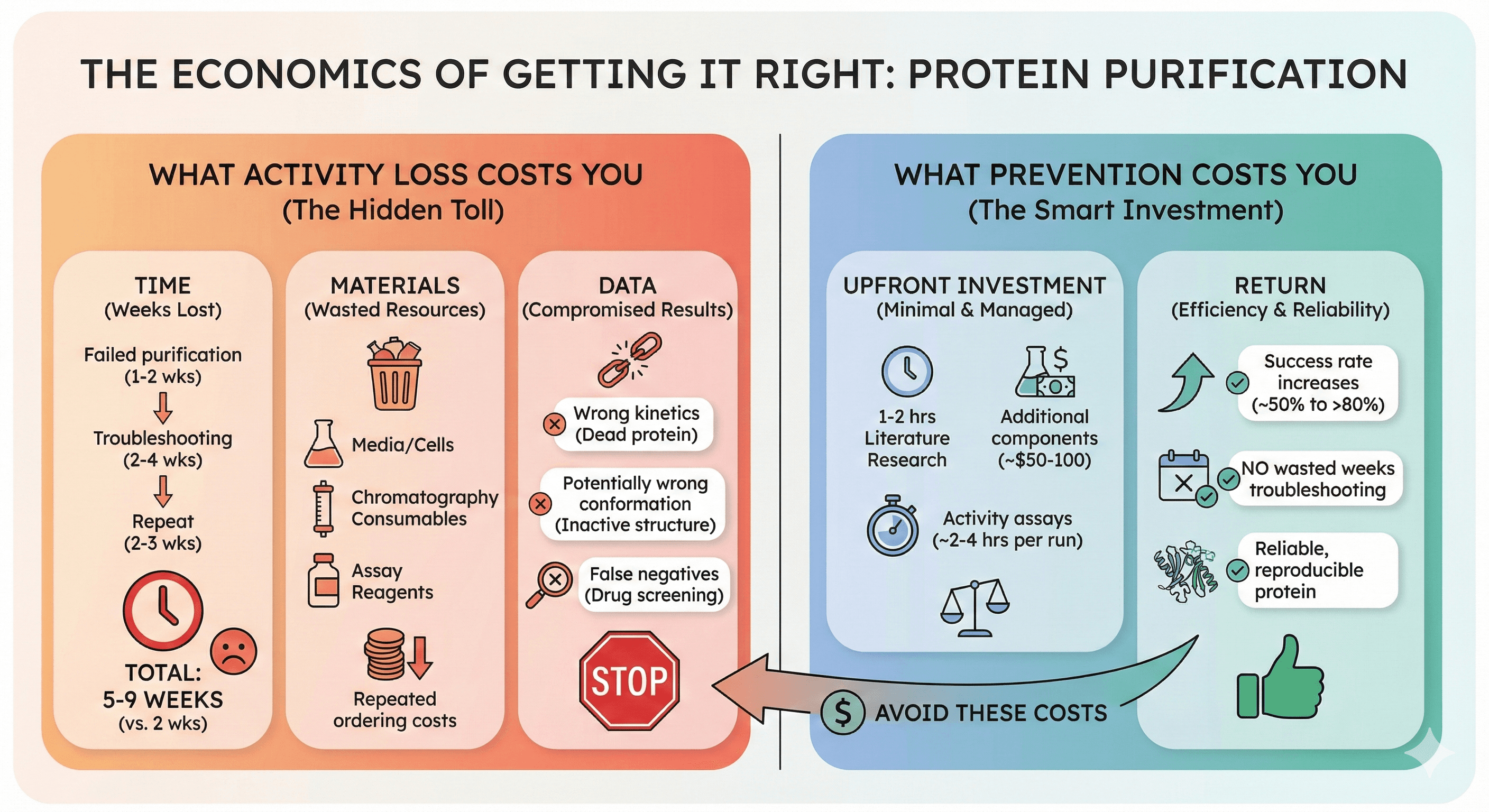

The Economics of Getting It Right

What Activity Loss Costs You

Time:

Failed purification: 1-2 weeks

Troubleshooting: 2-4 weeks

Repeat with modifications: 2-3 weeks

Total: 5-9 weeks for what should have been 2 weeks

Materials:

Wasted expression (media, cells, inducer)

Wasted chromatography consumables

Wasted activity assay reagents

Repeated ordering costs

Data:

Biochemical characterization with dead protein = wrong kinetics

Structural studies with inactive protein = potentially wrong conformation

Drug screening with compromised target = false negatives

What Prevention Costs You

Upfront investment:

1-2 hours literature research on protein requirements

Additional buffer components (~$50-100)

Activity assays at each step (~2-4 hours per purification)

Return:

First-time success rate improves from ~50% to >80%

No wasted weeks troubleshooting

Reliable, reproducible protein

The Bottom Line

Purity is not activity. The most common reasons for activity loss during purification are:

Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

Metal stripping | Avoid EDTA, include native metal |

Cofactor loss | Include cofactor in all buffers |

Oxidative damage | Use appropriate reducing agents |

Proteolysis | Work fast, use inhibitors |

Aggregation | Know solubility limits, use stabilizers |

Wrong conditions | Optimize buffer for your specific protein |

The difference between a failed purification and a successful one is often not technique—it's knowledge. Knowing what your protein needs before you start purification prevents most activity loss problems.

Protein-Specific Purification Planning

For researchers working with challenging proteins, platforms like Orbion can help identify potential purification problems before you encounter them:

Metal binding site prediction: Know which metals your protein requires

Cofactor binding analysis: Identify cofactor requirements from sequence

PTM prediction: Understand modification requirements

Disorder and aggregation prediction: Anticipate concentration limits

The goal is to design your purification around your protein's requirements—not discover them after activity is already lost.

References

Block H, et al. (2009). Immobilized-metal affinity chromatography (IMAC): a review. Methods in Enzymology, 463:439-473. PMC3134162

Krizek BA, et al. (1993). That zincing feeling: the effects of EDTA on the behaviour of zinc-binding transcriptional regulators. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 268(17):12387-12392. PMC1133908

Londer YY, et al. (2018). Improved method for the incorporation of heme cofactors into recombinant proteins using Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. Biochemistry, 57(19):2764-2770. Link

Sutherland MC, et al. (2021). In vitro reconstitution reveals major differences between human and bacterial cytochrome c synthases. eLife, 10:e64891. PMC8112865

Ocaña-Calahorro F, et al. (2022). Protein purification strategies must consider downstream applications and individual biological characteristics. Protein Expression and Purification, 191:106026. PMC8991485

Ryan BJ & Henehan GT. (2016). Avoiding proteolysis during protein purification. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1485:53-69. PubMed

Bondos SE & Bhattacharya A. (2003). Detection and prevention of protein aggregation before, during, and after purification. Analytical Biochemistry, 316(2):223-231. PubMed

Cleland WW. (1964). Dithiothreitol, a new protective reagent for SH groups. Biochemistry, 3:480-482. ScienceDirect