Blog

From Structure to Experiment: What Computational Biologists Miss

Jan 30, 2026

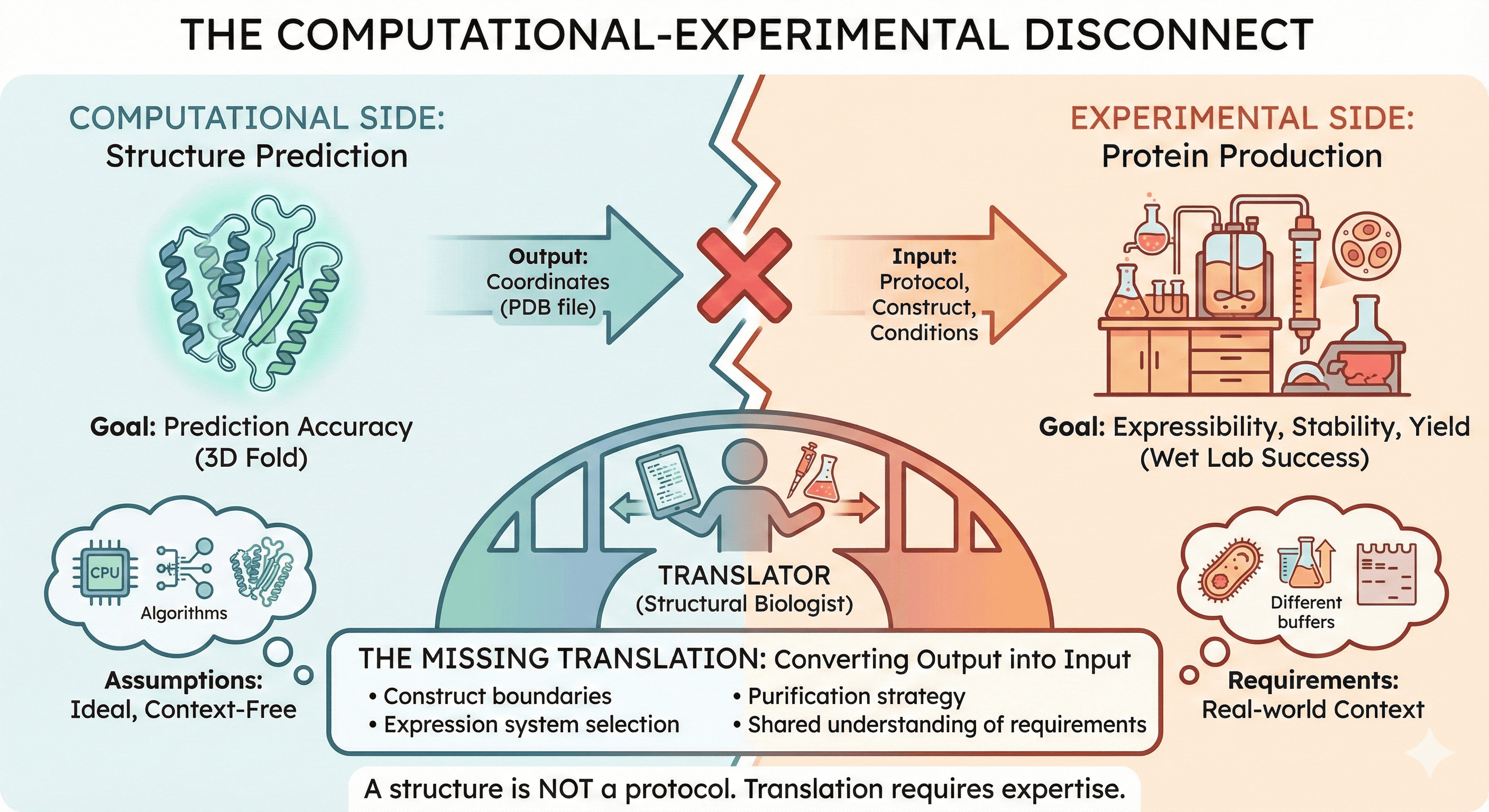

Your collaborator ran AlphaFold. They sent you a beautiful PDB file and a confident email: "Here's the structure. Let me know when you have crystals." Three months later, you still don't have soluble protein. The structure prediction was perfect. Everything else was missing.

This is the translation gap—the space between computational predictions and experimental reality. It's where projects stall, collaborations fracture, and beautiful in silico work dies in the test tube.

Key Takeaways

A structure is not a protocol: Knowing the 3D fold doesn't tell you how to make the protein

Context is everything: Expression system, construct boundaries, purification strategy—none of this comes from structure prediction

Computational biologists optimize for prediction accuracy: Wet lab success requires optimizing for expressibility, stability, and yield

The handoff fails when assumptions go unstated: Both sides need shared understanding of requirements

Translation requires translation: Someone has to convert computational output into experimental input

The Gap Nobody Talks About

The Computational View

From a computational perspective, the problem is solved:

Structure predicted with high confidence

Binding site identified

Mutations suggested for optimization

Paper-ready figures generated

Deliverables produced: PDB file, prediction confidence metrics, annotated images.

The Experimental View

From an experimental perspective, the work hasn't started:

What expression system do I use?

Where should I truncate the sequence?

What tag do I add, and where?

What's the purification strategy?

How do I know if the protein is functional?

Deliverables needed: Expressible construct, purification protocol, functional assay, milligrams of pure protein.

The Gap

The structure prediction provides the endpoint (what the protein looks like). The experiment requires the pathway (how to get there).

This gap is not technical—it's conceptual. Computational and experimental biologists often speak different languages about the same protein.

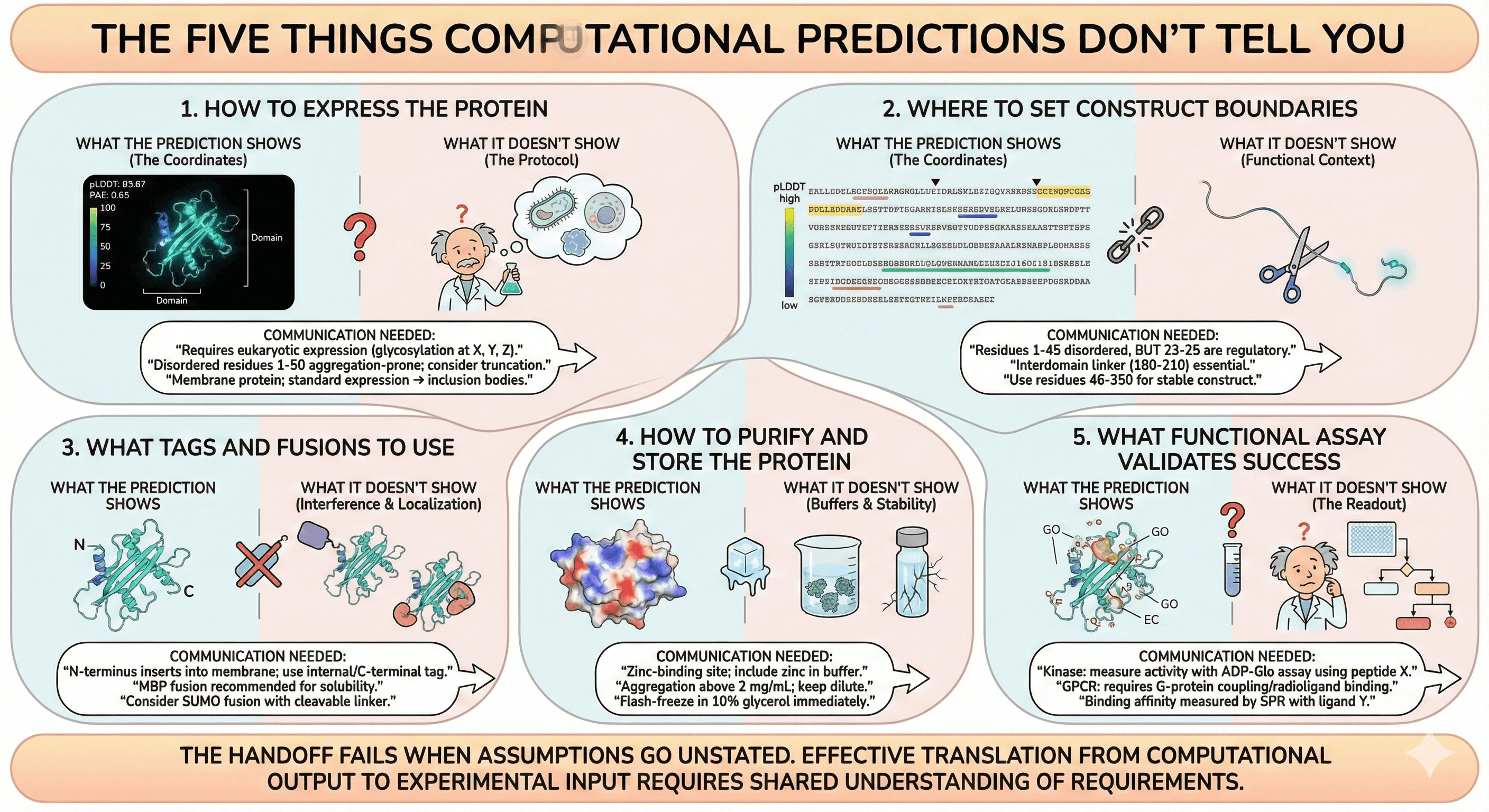

The Five Things Computational Predictions Don't Tell You

1. How to Express the Protein

What the prediction shows:

The folded structure of the full-length sequence

Confidence scores (pLDDT, PAE)

Domain architecture

What it doesn't show:

Whether E. coli, yeast, insect, or mammalian cells are required

Whether the full-length protein will express at all

What happens to disordered regions during expression

Which expression conditions (temperature, media, induction) to use

The consequence:

A collaborator receives a beautiful structure of a glycoprotein. They assume (because nothing says otherwise) that E. coli will work. They spend 8 weeks making expression constructs that will never produce functional protein because the glycans are essential for folding.

What should be communicated:

"This protein has N-glycosylation sites at positions X, Y, Z. It will require eukaryotic expression."

"Residues 1-50 are disordered and aggregation-prone. Consider truncation."

"This is a membrane protein. Standard expression will produce inclusion bodies."

2. Where to Set Construct Boundaries

What the prediction shows:

The full-length structure

Which regions are confident vs. uncertain (pLDDT)

Domain boundaries (sometimes)

What it doesn't show:

Whether disordered termini are functional or just aggregation liabilities

Where exactly to cut without hitting structured regions

Whether domain boundaries are cleavable or essential for folding

The consequence:

A structure shows a protein with a long N-terminal tail (pLDDT < 30). The experimentalist interprets this as "disordered, remove it." But the tail contains a regulatory phosphorylation site that the computational analysis didn't highlight. The truncated protein is stable but unregulated—and the data is uninterpretable.

What should be communicated:

"Residues 1-45 are disordered. Consider truncation, BUT residues 23-25 are a known regulatory motif."

"The interdomain linker (residues 180-210) is flexible but essential for domain communication."

"Construct boundaries should be residues 46-350 for stable, functional protein."

3. What Tags and Fusions to Use

What the prediction shows:

The protein structure in isolation

N and C-terminal accessibility

What it doesn't show:

Whether an N-terminal tag will interfere with function

Whether the C-terminus is buried (tag will disrupt fold)

Which fusion partners improve expression vs. cause problems

Whether tags can be cleaved (accessibility of protease site)

The consequence:

A collaborator says "add a His-tag for purification." The experimentalist adds an N-terminal His-tag. But the N-terminus is essential for membrane insertion—now the protein doesn't localize correctly. The purification "works" (protein is pure), but the functional assay fails.

What should be communicated:

"N-terminus inserts into membrane. Use internal tag or C-terminal tag."

"MBP fusion recommended for solubility. Place TEV site at residue 45."

"This protein tends to aggregate. Consider SUMO fusion with cleavable linker."

4. How to Purify and Store the Protein

What the prediction shows:

Protein structure

Surface properties (charge, hydrophobicity) if analyzed

What it doesn't show:

What buffers stabilize the protein

What detergents are required (for membrane proteins)

Whether the protein survives freeze-thaw

What concentration is achievable before aggregation

Whether cofactors need to be added

The consequence:

The structure is predicted. The experimentalist expresses the protein, runs affinity purification, elutes into standard buffer. The protein crashes out during concentration. Or it survives purification but is dead by the next morning. The computational collaborator asks "why is this taking so long?"

What should be communicated:

"This protein has a zinc-binding site. Include zinc in purification buffer."

"Predicted aggregation above 2 mg/mL. Keep dilute."

"Flash-freeze in 10% glycerol immediately after purification."

5. What Functional Assay Validates Success

What the prediction shows:

Structure (what it looks like)

Binding sites (where it might act)

Annotations (GO terms, EC numbers)

What it doesn't show:

How to measure that the protein is active

What substrate to use

What positive control validates the assay

Whether the predicted binding site is accessible in your construct

The consequence:

Protein is expressed, purified, concentrated, and handed back to the computational collaborator. "Great, now confirm the binding site with mutagenesis." But the experimentalist has no idea how to measure binding. There's no established assay. The protein sits in the freezer while both sides wait for the other to figure it out.

What should be communicated:

"This is a kinase. Activity can be measured with ADP-Glo assay using peptide substrate X."

"This is a GPCR. Functional reconstitution requires G-protein coupling or radioligand binding."

"Binding affinity can be measured by SPR with ligand Y."

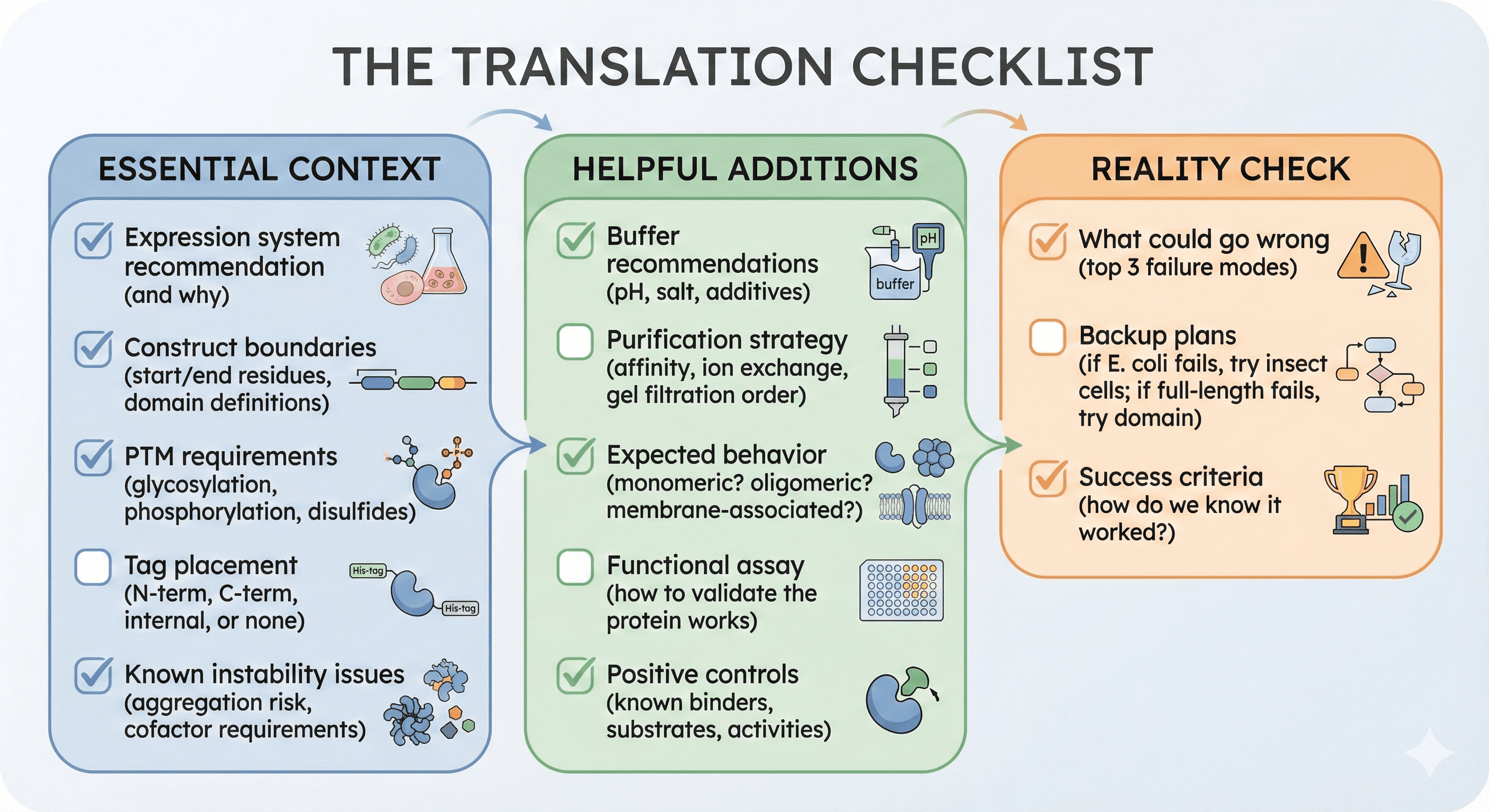

The Translation Checklist

Before handing off a computational prediction to an experimentalist, provide:

Essential Context

[ ] Expression system recommendation (and why)

[ ] Construct boundaries (start/end residues, domain definitions)

[ ] PTM requirements (glycosylation, phosphorylation, disulfides)

[ ] Tag placement (N-term, C-term, internal, or none)

[ ] Known instability issues (aggregation risk, cofactor requirements)

Helpful Additions

[ ] Buffer recommendations (pH, salt, additives)

[ ] Purification strategy (affinity, ion exchange, gel filtration order)

[ ] Expected behavior (monomeric? oligomeric? membrane-associated?)

[ ] Functional assay (how to validate the protein works)

[ ] Positive controls (known binders, substrates, activities)

Reality Check

[ ] What could go wrong (top 3 failure modes)

[ ] Backup plans (if E. coli fails, try insect cells; if full-length fails, try domain)

[ ] Success criteria (how do we know it worked?)

Common Miscommunications

"The structure looks great"

What the computational biologist means: AlphaFold confidence is high. The prediction is reliable.

What the experimentalist hears: The protein will be easy to produce.

Reality: Prediction confidence has no correlation with expression difficulty. A confidently predicted GPCR is still a GPCR—notoriously difficult to express.

"The protein should be stable"

What the computational biologist means: The fold is thermodynamically favorable.

What the experimentalist hears: The protein won't aggregate or lose activity.

Reality: Thermodynamic stability (the fold is favorable) is different from kinetic stability (the protein survives handling). A stable fold can still unfold during expression, aggregation during purification, or deactivate during storage.

"Just add a His-tag"

What the computational biologist means: Affinity purification is the standard approach.

What the experimentalist hears: Any His-tag placement will work.

Reality: Tag placement matters enormously. N-terminal, C-terminal, and internal tags all have different effects on expression, folding, and function. The "just" implies a simplicity that doesn't exist.

"The binding site is here"

What the computational biologist means: Based on prediction/annotation, residues X-Y form the binding site.

What the experimentalist hears: Mutagenesis of residues X-Y will confirm binding.

Reality: Predicted binding sites may not be accessible in all constructs/conformations. The experimentalist needs to know whether the site is surface-exposed, occluded, or only formed upon conformational change.

"Let me know when you have protein"

What the computational biologist means: Call me when you're ready for the next computational step.

What the experimentalist hears: Figure out expression yourself; it's not my problem.

Reality: Expression optimization may require iterative computational input (new constructs, fusion designs, mutation suggestions). A single handoff rarely works.

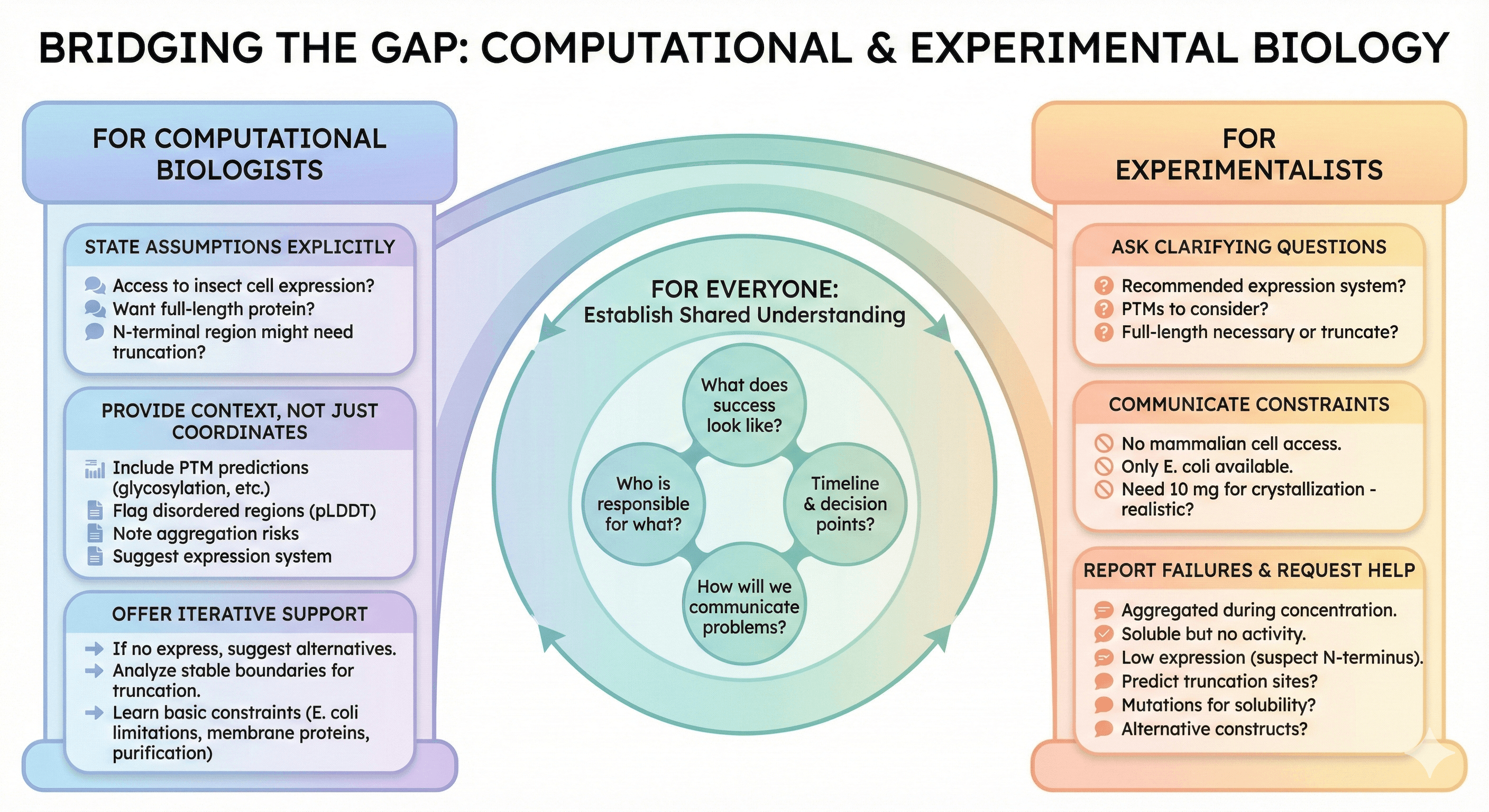

Bridging the Gap

For Computational Biologists

Before sending predictions:

State your assumptions explicitly

"I'm assuming you have access to insect cell expression."

"This analysis assumes you want full-length protein."

"I'm not sure about the N-terminal region; it might need truncation."

Provide context, not just coordinates

Include PTM predictions

Flag disordered regions

Note aggregation risks

Suggest expression system

Offer iterative support

"If this construct doesn't express, let me know—I can suggest alternatives."

"If you need to truncate, I can analyze where the stable boundaries are."

Learn basic expression constraints

Know when E. coli won't work

Understand why membrane proteins are hard

Appreciate that purification is non-trivial

For Experimentalists

Before starting work:

Ask clarifying questions

"What expression system do you recommend?"

"Are there PTMs I need to consider?"

"Is the full-length protein necessary, or can I truncate?"

Communicate constraints

"I don't have access to mammalian cell expression."

"Our lab only does E. coli."

"I need 10 mg for crystallization—is that realistic?"

Report failures informatively

"The protein expressed but aggregated during concentration."

"I got soluble protein, but activity assay showed no function."

"Expression was low—I suspect the disordered N-terminus."

Request specific computational help

"Can you predict where to truncate?"

"What mutations might improve solubility?"

"Is there an alternative construct that might express better?"

For Everyone

Establish shared understanding:

What does success look like?

Who is responsible for what?

What's the timeline and decision points?

How will we communicate problems?

Case Study: The Collaborative Translation

The Setup

Target: Human membrane protein implicated in neurodegeneration Goal: Structural characterization for drug discovery Team: Computational group + structural biology lab

The Failed Approach

Email from computational:

"Attached is the AlphaFold structure. The binding site is in the extracellular domain. Let me know when you have crystals."

What happened:

Structural lab tried E. coli expression (failed—membrane protein)

Tried insect cells (low yield, aggregation)

Tried mammalian cells (slight improvement)

8 months of troubleshooting with no input from computational side

The Successful Approach

Revised communication:

"This is a single-pass membrane protein. Expression recommendations:

System: Sf9 insect cells with baculovirus (HEK293 as backup)

Construct: Residues 1-350 (full TM + extracellular domain)

Tag: C-terminal His8 (N-terminus has signal peptide)

Note: Extracellular domain alone (residues 51-350) is an alternative if full-length fails

Risks: Two N-glycosylation sites (N123, N245) are predicted—may need mutations to N123Q/N245Q for crystallization

Binding site: Residues 180-220 form the predicted pocket—keep these intact

Validation: Ligand X binds with ~100 nM Kd (use for functional assay)"

What happened:

First attempt (Sf9, full-length): Low yield, microcrystals only

Second attempt (HEK293, glycan mutants): Better yield, diffraction to 2.5 Å

Structure solved in 4 months

The Difference

The successful approach translated computational output into experimental parameters. It anticipated problems, provided alternatives, and enabled rapid iteration.

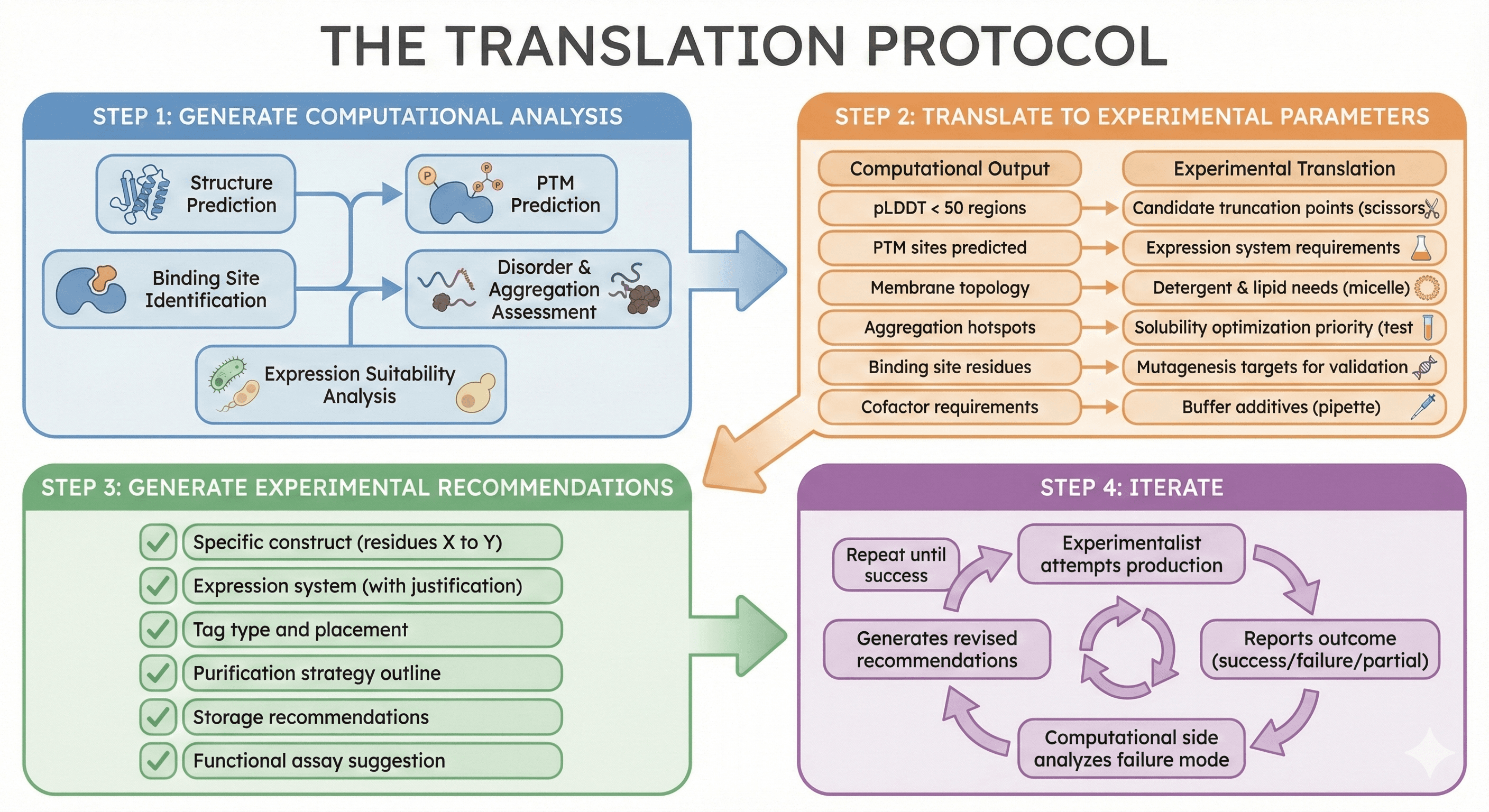

The Translation Protocol

Step 1: Generate Computational Analysis

Structure prediction

PTM prediction

Binding site identification

Disorder and aggregation assessment

Expression suitability analysis

Step 2: Translate to Experimental Parameters

Computational Output | Experimental Translation |

|---|---|

pLDDT < 50 regions | Candidate truncation points |

PTM sites predicted | Expression system requirements |

Membrane topology | Detergent and lipid needs |

Aggregation hotspots | Solubility optimization priority |

Binding site residues | Mutagenesis targets for validation |

Cofactor requirements | Buffer additives |

Step 3: Generate Experimental Recommendations

Specific construct (residues X to Y)

Expression system (with justification)

Tag type and placement

Purification strategy outline

Storage recommendations

Functional assay suggestion

Step 4: Iterate

Experimentalist attempts production

Reports outcome (success/failure/partial)

Computational side analyzes failure mode

Generates revised recommendations

Repeat until success

The Emerging Standard

What Modern Platforms Should Provide

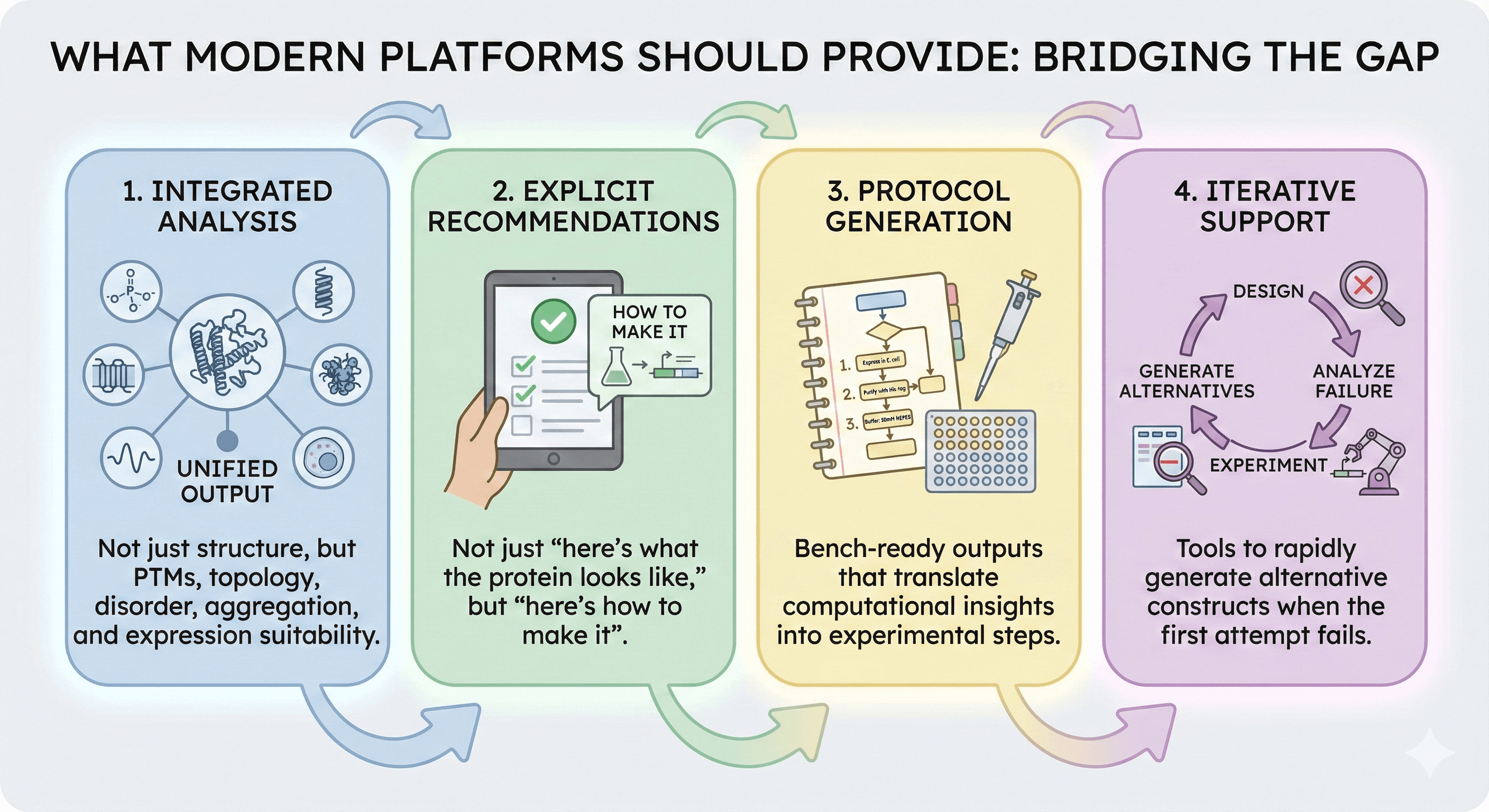

The gap between prediction and experiment isn't being solved by better predictions. It's being solved by better context.

Modern protein research platforms should deliver:

Integrated analysis - Not just structure, but PTMs, topology, disorder, aggregation, and expression suitability

Explicit recommendations - Not just "here's what the protein looks like," but "here's how to make it"

Protocol generation - Bench-ready outputs that translate computational insights into experimental steps

Iterative support - Tools to rapidly generate alternative constructs when the first attempt fails

The Goal

The goal isn't to replace experimental expertise. It's to give experimentalists the context they need to succeed on the first attempt—or at least the second, rather than the tenth.

The Bottom Line

Structure prediction was never the finish line. It's the starting line.

What Prediction Gives You | What Experiment Requires |

|---|---|

Coordinates | Expressible construct |

Confidence scores | Purification protocol |

Annotations | Functional validation |

Pretty pictures | Milligrams of pure protein |

The gap between these two columns is where projects fail. Bridging that gap requires:

Explicit communication of context and assumptions

Translation of computational outputs into experimental parameters

Iterative collaboration, not one-time handoffs

Tools that provide context, not just predictions

The most common reason structural biology projects fail isn't bad predictions or bad experiments. It's bad translation between the two.

Context-Aware Experimental Planning

For researchers working across the computational-experimental divide, platforms like Orbion aim to close this gap by providing:

Integrated context analysis that combines structure, PTMs, binding sites, and stability predictions

Expression suitability assessment that recommends appropriate systems based on protein properties

Protocol generation that translates computational insights into bench-ready experimental plans

Iterative optimization through construct and mutation analysis when initial attempts fail

The goal is to make "here's the structure" into "here's how to make the protein"—before the experimentalist spends months discovering the hard way what the computational analysis could have predicted.

References

Jumper J, et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596:583-589. Link

Tunyasuvunakool K, et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature, 596:590-596. Link

Structural Genomics Consortium. (2008). Protein production and purification. Nature Methods, 5:135-146. Link

Gräslund S, et al. (2008). Protein production and purification. Nature Methods, 5:135-146. Link

Savitsky P, et al. (2010). High-throughput production of human proteins for crystallization: The SGC experience. Journal of Structural Biology, 172(1):3-13. Link

Rosano GL & Ceccarelli EA. (2014). Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: advances and challenges. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5:172. Link