Blog

Why Stabilizing Mutations Sometimes Make Everything Worse

Jan 28, 2026

You ran the stability prediction software. It suggested L134I would increase thermal stability by 3°C. You made the mutation, expressed the protein, measured the Tm, and celebrated: 47°C to 50°C, just as predicted. Then you ran the activity assay. The enzyme was dead.

Welcome to the stability-function tradeoff—the reason that "stabilizing mutations" can destroy your protein.

Key Takeaways

Stability and function are often antagonistic: Mutations that rigidify the fold can lock out required conformational changes

ΔΔG alone is insufficient: A mutation can stabilize the protein while killing activity, increasing aggregation, or removing essential modifications

Location matters more than magnitude: A +1 kcal/mol mutation in the active site is worse than a +3 kcal/mol mutation in a scaffold region

Multi-metric analysis prevents surprises: Evaluate stability, activity, aggregation, and modifications together

The best mutations stabilize without functional cost: They exist, but they require careful selection

The Stability-Function Paradox

Why Do We Want Stability?

Stable proteins are easier to work with:

Expression: Stable proteins fold properly, avoiding inclusion bodies

Purification: Stable proteins survive handling without aggregating

Storage: Stable proteins have longer shelf life

Crystallization: Stable proteins form better crystals

Therapeutics: Stable biologics are more manufacturable

The logic seems simple: If the protein is unstable, stabilize it. Find mutations that increase Tm or decrease ΔΔG, make the changes, problem solved.

Why Does This Fail?

Proteins aren't static structures. They're dynamic machines that function through motion (Henzler-Wildman & Kern, 2007):

Enzymes require domain movements for catalysis

Receptors undergo conformational changes upon ligand binding

Channels open and close in response to signals

Antibodies need CDR flexibility for affinity maturation

Stabilizing mutations reduce dynamics. That's the whole point—you're making the protein more rigid. But if the protein needs flexibility to work, rigidifying it kills function. This stability-activity tradeoff is well-documented across enzyme families (Tokuriki et al., 2008).

The paradox: Stability is good, but too much stability prevents function.

The Five Ways Stabilizing Mutations Go Wrong

Problem 1: Locking the Active Site

The scenario:

Enzyme has flexible active site loop that opens to accept substrate

Mutation rigidifies the loop (increases Tm)

Loop can no longer open

Substrate can't enter

Activity: zero

Example: Lysozyme

Wild-type lysozyme:

Active site has mobile loop (residues 65-75)

Loop opens to accommodate polysaccharide substrate

Closes for catalysis

Stabilizing mutation (hypothetical: G67A):

Removes glycine flexibility

Loop can't open

Substrate excluded

Tm +2°C, activity -90%

The rule: Never stabilize active site residues without checking dynamics requirements.

Problem 2: Preventing Allosteric Communication

The scenario:

Protein has allosteric regulation

Binding at one site affects conformation at another

Stabilizing mutation breaks the conformational link

Allostery lost

Example: Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin's cooperative oxygen binding depends on:

Conformational change at one subunit

Transmitted to other subunits

T-state to R-state transition

A mutation that over-stabilizes T-state:

Blocks transition to R-state

Destroys cooperativity

Now binds oxygen poorly

The rule: Allosteric proteins are especially sensitive to stabilizing mutations.

Problem 3: Creating Aggregation Hotspots

The scenario:

Mutation adds hydrophobicity for stability (e.g., K→L)

The new hydrophobic residue is surface-exposed

Creates an aggregation-prone patch

Protein is more stable but aggregates at concentration

The perverse outcome: Tm increases, but practical solubility decreases.

Example: Antibody engineering

Original residue: K52 (charged, soluble) Stabilizing mutation: K52L (hydrophobic core, ΔΔG = -0.8 kcal/mol)

Result:

Individual Fab is more stable

But surface hydrophobic patch promotes aggregation

At therapeutic concentrations (>100 mg/mL): precipitates

The rule: ΔΔG stabilization at the surface can cause aggregation.

Problem 4: Removing PTM Sites

The scenario:

Residue is a PTM site (phosphorylation, glycosylation)

The modification is essential for function or localization

Mutation for stability removes the modifiable residue

Protein loses its regulatory mechanism

Example: Kinase activation loop

Many kinases have activation loop phosphorylation:

Unphosphorylated: Low activity (autoinhibited)

Phosphorylated: High activity (active)

Stabilizing mutation that removes phosphorylation site:

Can lock kinase in either state

If locked inactive: Dead enzyme

If locked active: Potential oncogene

Real case: Mutations at kinase activation loops are frequently oncogenic. Some "stabilizing" mutations cause cancer.

The rule: Always check if target residue is a PTM site before mutating.

Problem 5: Disrupting Binding Interfaces

The scenario:

Protein interacts with partners (substrates, cofactors, other proteins)

Interface residues are sometimes suboptimal for stability

Mutating them for stability disrupts binding

Protein is more stable but can't do its job

Example: Enzyme-cofactor interaction

Many enzymes bind cofactors (NAD, FAD, heme, metal ions):

Cofactor binding site has specific geometry

Residues evolved for binding, not for protein stability

These residues might look "improvable" to stability predictors

Mutation at cofactor site:

May stabilize the apo protein

But disrupts cofactor binding

No cofactor = no activity

The rule: Binding sites are often stability "weak points" by design.

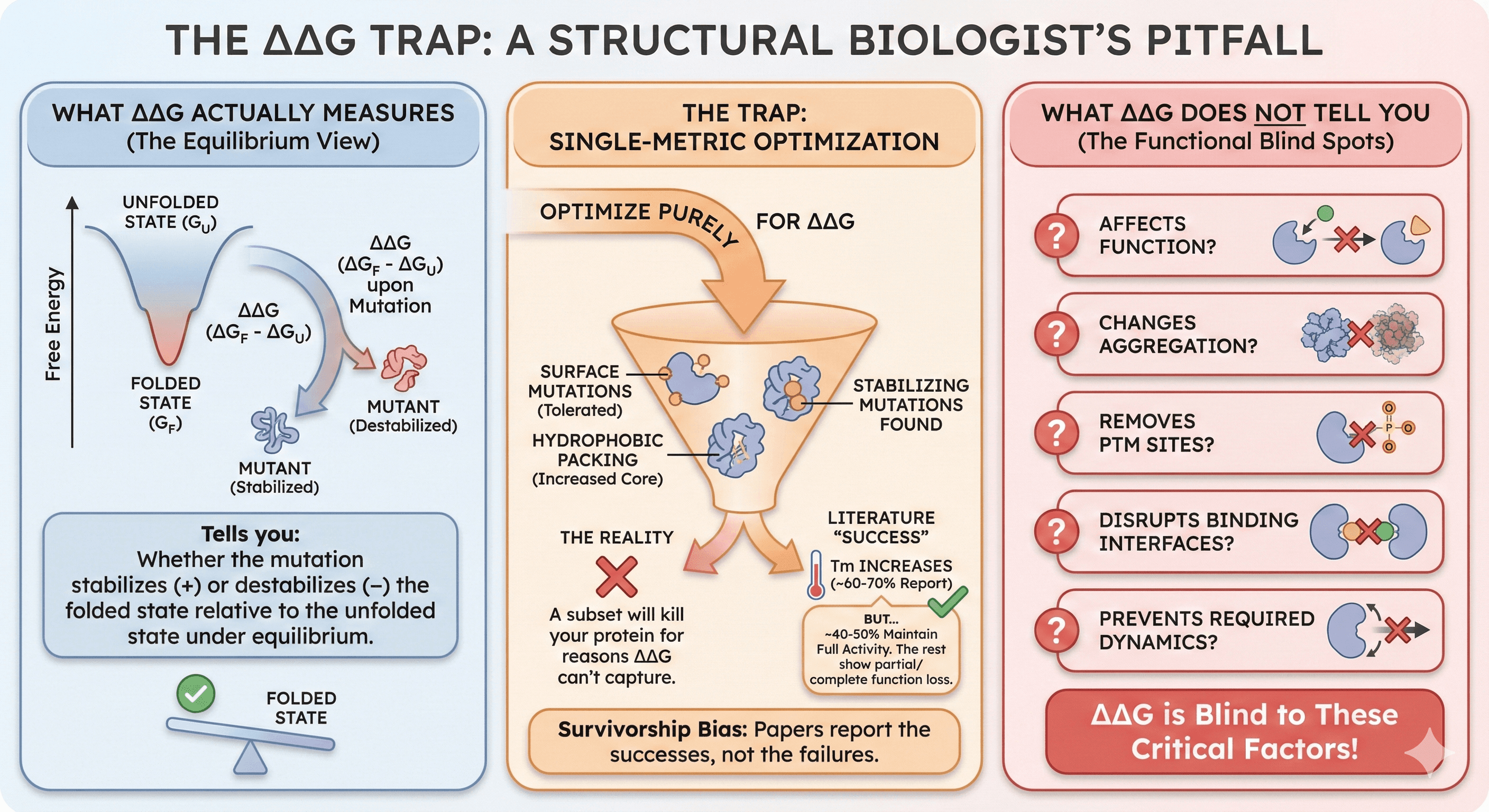

The ΔΔG Trap

What ΔΔG Actually Measures

ΔΔG (change in Gibbs free energy upon mutation) tells you:

Whether the mutation stabilizes (+) or destabilizes (-) the folded state

Relative to the unfolded state

Under equilibrium conditions

What ΔΔG does NOT tell you:

Whether the mutation affects function

Whether it changes aggregation propensity

Whether it removes PTM sites

Whether it disrupts binding interfaces

Whether it prevents required dynamics

Why Single-Metric Optimization Fails

If you optimize purely for ΔΔG:

You'll find stabilizing mutations

Many will be on the protein surface (where mutations are most tolerated)

Some will add hydrophobicity (increasing core packing)

A subset will kill your protein for reasons ΔΔG can't capture

The numbers:

Literature reports ~60-70% success rate for ΔΔG-predicted stabilizing mutations

"Success" means Tm increases

But only ~40-50% maintain full activity

The rest show partial or complete function loss

Survivorship bias: Papers report the mutations that worked. The failures don't get published.

Multi-Metric Mutation Analysis

The Correct Approach

Evaluate each candidate mutation across multiple dimensions:

Metric | What It Tells You | Red Flag |

|---|---|---|

ΔΔG | Fold stability | Destabilizing (< -1 kcal/mol) |

ΔTm | Thermal stability | Significant decrease |

Δ Activity | Function | Any decrease |

Δ Aggregation | Solubility | Increase |

Δ Binding | Partners/cofactors | Disruption |

PTM site | Modifications | Removal |

Δ Disorder | Local flexibility | Wrong direction |

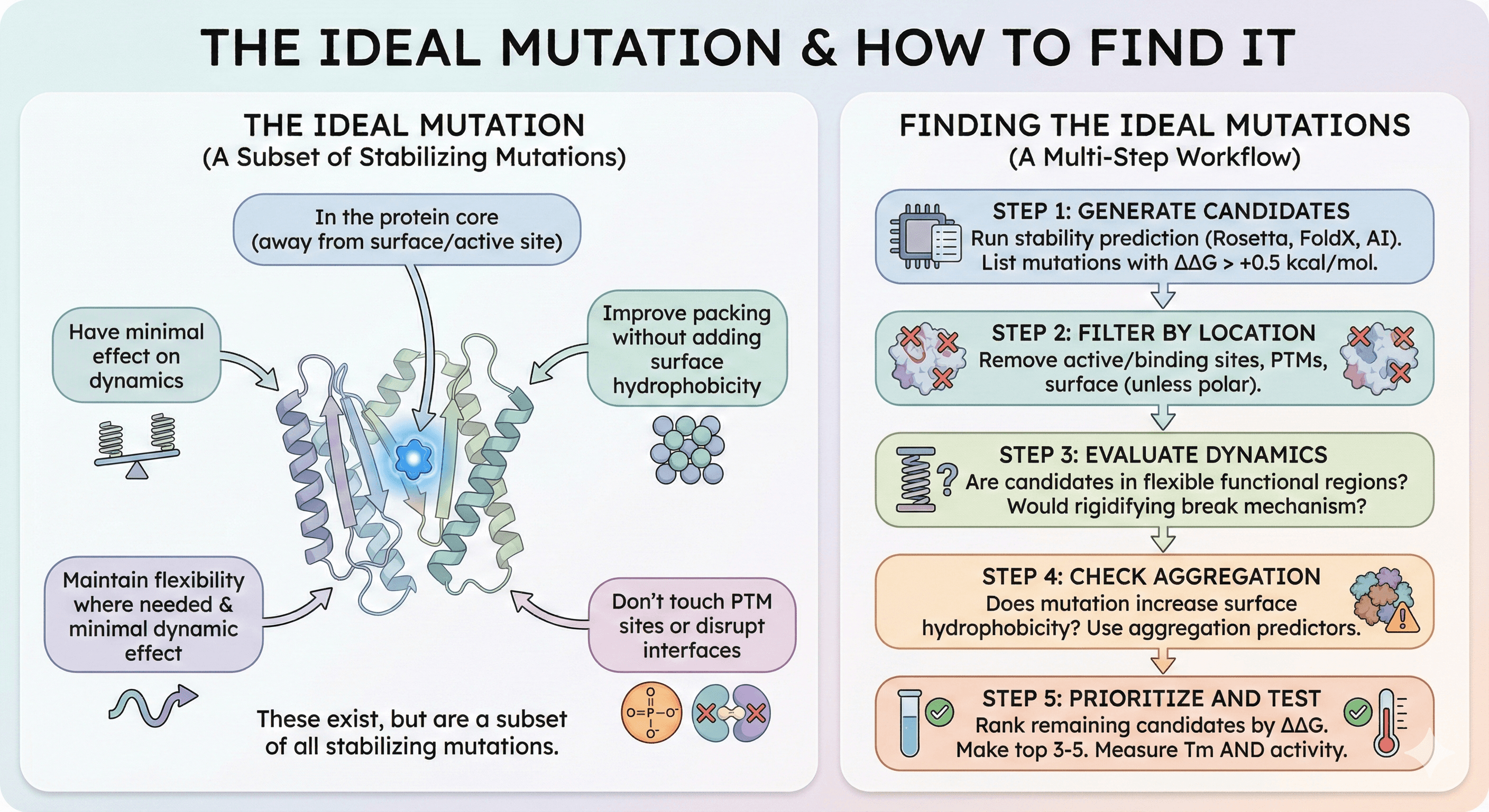

The Ideal Mutation

The best stabilizing mutations are:

In the protein core (away from surface and active site)

Improve packing without adding surface hydrophobicity

Maintain or increase local flexibility where needed

Don't touch PTM sites

Don't disrupt interfaces

Have minimal effect on dynamics

These exist, but they're a subset of all stabilizing mutations.

Finding the Ideal Mutations

Step 1: Generate candidates

Run stability prediction (Rosetta, FoldX, or AI tools)

List all mutations with ΔΔG > +0.5 kcal/mol

Step 2: Filter by location

Remove active site residues

Remove known binding site residues

Remove PTM sites

Remove surface residues (unless switching to charged/polar)

Step 3: Evaluate dynamics

Are any candidates in flexible regions required for function?

Would rigidifying this region break the mechanism?

Step 4: Check aggregation

Does the mutation increase surface hydrophobicity?

Use aggregation predictors on mutant sequence

Step 5: Prioritize and test

Rank remaining candidates by ΔΔG

Make top 3-5 mutations

Measure Tm AND activity

Case Studies in Mutation Tradeoffs

Case 1: The Dead Enzyme

Target: Metabolic enzyme for biochemical assay Problem: Enzyme loses activity within 24 hours at 4°C Goal: Stabilize for longer shelf life

Approach 1 (failed):

Ran Rosetta ΔΔG prediction

Top mutation: F67W (core packing improvement)

Made mutation, measured Tm: +4°C

Measured activity: 5% of wild-type

F67 is adjacent to active site; larger Trp blocks substrate entry

Approach 2 (successful):

Filtered Rosetta results to exclude active site region

Top mutation outside active site: V198I (distant from catalytic center)

Made mutation, measured Tm: +2°C

Measured activity: 100% of wild-type

Shelf life: Extended from 24 hours to 1 week

Lesson: Exclude the functional machinery from stability optimization.

Case 2: The Aggregating Antibody

Target: Therapeutic antibody for chronic disease Problem: Aggregates above 50 mg/mL (need 150 mg/mL for subcutaneous) Goal: Stabilize to prevent aggregation

Approach 1 (failed):

Identified flexible CDR loop with low Tm

Rigidified loop with V31I (ΔΔG = +1.1 kcal/mol)

Tm increased from 62°C to 66°C

Aggregation unchanged

Binding affinity dropped 10-fold

Approach 2 (successful):

Analyzed aggregation propensity, not just stability

Identified surface hydrophobic patch (I53, F55)

Mutated to polar: I53S, F55T (ΔΔG = +0.3 kcal/mol only)

Tm slightly increased (63°C)

Aggregation threshold: 50 mg/mL → 180 mg/mL

Binding affinity: maintained

Lesson: Aggregation and stability are different problems requiring different solutions.

Case 3: The Unregulated Kinase

Target: Kinase for drug discovery (need stable protein for crystallography) Problem: Kinase is unstable, Tm = 42°C, can't crystallize Goal: Increase Tm for structural studies

Approach 1 (dangerous):

Predicted stabilizing mutation T201V (in activation loop)

T201 is a phosphorylation site

Mutation locks kinase in partially active state

Tm increases to 52°C (stable!)

But: This is now a different conformational state

Crystal structure would not represent physiological state

Approach 2 (correct):

Identified stabilizing mutations outside regulatory regions

Mutations in core helices: L87I, A145V

Tm increased to 50°C

Activation loop still functional

Phosphorylation still possible

Crystal structure represents regulatable kinase

Lesson: Don't confuse "stable" with "correct state."

The Right Way to Stabilize

Step-by-Step Workflow

What to Optimize (And What Not To)

Good targets for stabilization:

Core hydrophobic residues (packing improvements)

Buried polar residues (hydrogen bond networks)

Surface residues (changing to charged/polar)

Loop regions (if not functionally required)

Bad targets for stabilization:

Active site (catalysis)

Binding site (substrates, cofactors, partners)

PTM sites (regulation)

Flexible regions required for mechanism

Interface residues (if function requires binding)

The Economics of Getting It Wrong

Time and Money

If you pick the wrong mutation:

Express mutant protein: 1-2 weeks

Purify and characterize: 1 week

Discover function is compromised: Day 1 of assays

Redesign and try again: Add 3-4 weeks

If you pick the right mutation first:

Same expression and purification: 2-3 weeks

Function confirmed: Day 1 of assays

Move forward with stable, functional protein

Difference: 3-4 weeks and the demoralizing experience of solving the wrong problem.

The Therapeutic Context

For biologics development:

A destabilizing mutation discovered in clinical trials = program termination

An aggregation-prone variant = formulation failure = manufacturing rebuild

Loss of PTM site = altered pharmacokinetics = potentially dangerous

The cost of wrong mutations in pharma: Millions of dollars and years of delay.

Tools for Multi-Metric Analysis

What's Available

Traditional stability predictors (ΔΔG only):

Rosetta: Gold standard, but complex

FoldX: Faster, widely used

MAESTRO: Quick empirical predictions

Limitations: Only predict fold stability, not function or other properties.

Aggregation predictors:

AGGRESCAN: Sequence-based hotspot detection

CamSol: Solubility prediction

AGGRESCAN3D: Structure-based

Limitations: Don't connect to stability or function.

What's missing: Integrated platforms that evaluate all dimensions simultaneously.

The Ideal Analysis

For each candidate mutation, you want to see:

ΔΔG: Is this actually stabilizing?

Δ Disorder: Am I rigidifying a region that needs flexibility?

Δ Aggregation: Am I creating a surface hydrophobic patch?

PTM impact: Am I removing a modification site?

Binding site check: Am I in or near a functional interface?

pLDDT change: Does the local structure prediction change?

The result: A mutation score that captures the full picture, not just one dimension.

The Bottom Line

Stability optimization isn't about maximizing ΔΔG. It's about finding the subset of stabilizing mutations that don't break anything else.

Metric Alone | Risk | Better Approach |

|---|---|---|

ΔΔG only | Functional loss | ΔΔG + location filter |

Tm only | Aggregation | Tm + aggregation |

Surface hydrophobicity | Aggregation | Balance with polar |

Any single metric | Missing the full picture | Multi-metric |

The paradox resolved: Stability and function can coexist—but only if you select mutations that are stabilizing in regions that don't matter for function.

The difference between a successful stabilization project and a failed one is usually one thing: checking more than just ΔΔG.

Comprehensive Variant Analysis

For researchers engineering protein stability, platforms like Orbion provide multi-dimensional variant analysis that goes beyond single-metric predictions:

Thermodynamic metrics: ΔTm, ΔΔG predictions

Structural/biophysical impacts: Changes in disorder, aggregation propensity, local confidence

Functional preservation: Binding site analysis, PTM site detection

Residue-level comparison: See exactly what changes at each position

The goal is to find stabilizing mutations that preserve function—not to blindly maximize stability and hope nothing breaks.

References

Henzler-Wildman K & Kern D. (2007). Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature, 450:964-972. Link

Tokuriki N, et al. (2008). How protein stability and new functions trade off. PLoS Computational Biology, 4(2):e1000002. PMC2904692

Schymkowitz J, et al. (2005). The FoldX web server: an online force field. Nucleic Acids Research, 33(Web Server issue):W382-W388. Link

Kellogg EH, et al. (2011). Role of conformational sampling in computing mutation-induced changes in protein structure and stability. Proteins, 79(3):830-838. Link

Bloom JD, et al. (2006). Protein stability promotes evolvability. PNAS, 103(15):5869-5874. Link

Wang X, et al. (2018). Antibody structure, instability, and formulation. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 96(1):1-26. Link

Ó Conchúir S, et al. (2015). A web resource for standardized benchmark datasets, metrics, and Rosetta protocols for macromolecular modeling and design. PLoS One, 10(9):e0130433. Link