Blog

Finding Druggable Pockets When the Active Site Is Too Conserved

Jan 26, 2026

Your kinase inhibitor is potent. Sub-nanomolar IC50. Beautiful binding to the ATP pocket. There's just one problem: it also inhibits 47 other kinases in the same family. The selectivity panel is a sea of red. Your drug candidate is toxic before it reaches the clinic.

The ATP binding site was the obvious target. It's also the most conserved pocket across the kinome. Every kinase binds ATP the same way. Your molecule can't tell them apart.

This is the selectivity problem—and it's why drug discovery increasingly looks beyond the active site.

Key Takeaways

Active sites are often too conserved for selective drug design (90%+ sequence identity across families)

Allosteric sites offer selectivity because they're under less evolutionary pressure

Cryptic pockets exist in many proteins but only appear in certain conformations

Protein-protein interaction sites are emerging targets but require different approaches

Computational methods can identify non-obvious binding sites before you screen

The Conservation Problem

Why Active Sites Are Poor Selectivity Targets

Evolution has shaped active sites for one purpose: catalysis. The residues that bind substrates and transition states are under intense selection pressure. Change them, and the enzyme dies.

The result:

Active sites are the most conserved regions of protein families

ATP-binding pockets across 500+ human kinases share >80% sequence identity

Substrate-binding sites in protease families are nearly identical

The pocket you're targeting looks the same in your target and its closest 50 relatives

The Numbers

Human kinome (Manning et al., 2002):

518 protein kinases

ATP pocket: 85-95% conserved across families

Approved kinase inhibitors: 70+ drugs

Selectivity failures: The majority bind >10 kinases at therapeutic doses (Klaeger et al., 2017)

Proteases:

Serine proteases share the catalytic triad (Ser-His-Asp)

Active site geometry: virtually identical

First-generation inhibitors: almost universally non-selective

Nuclear receptors:

Ligand-binding domain: highly conserved

Steroid hormone receptors: cross-reactivity is the rule, not exception

The Clinical Consequence

Non-selective drugs cause:

Off-target toxicity: Hitting related proteins causes side effects

Narrow therapeutic window: The dose that's effective is close to toxic

Drug-drug interactions: Multiple kinases affected by the same drug

Resistance: Easy to evolve resistance when many targets exist

Example: First-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Imatinib (Gleevec) was designed against BCR-ABL kinase (Druker et al., 2001). But it also hits:

c-KIT (useful for GIST tumors)

PDGFR (causes fluid retention)

c-ABL in normal cells (bone marrow suppression)

The "off-target" effects became indications (GIST) or dose-limiting toxicities (edema, cytopenias).

Beyond the Active Site: Four Alternatives

Alternative 1: Allosteric Sites

What they are: Binding sites distant from the active site that modulate function through conformational change.

Why they're selective:

Not under substrate-binding pressure

Evolve independently of catalytic function

Often unique to specific proteins or subfamilies

How allosteric drugs work:

Small molecule binds to allosteric site

Binding causes conformational change

Conformational change alters active site (activates or inhibits)

Function is modulated without competing with substrate

Examples of allosteric successes:

Drug | Target | Allosteric Site | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

Trametinib | MEK1/2 | Allosteric pocket | Highly selective for MEK |

Asciminib | BCR-ABL | Myristate pocket | Overcomes imatinib resistance |

Venetoclax | BCL-2 | BH3 groove | First-in-class protein-protein disruptor |

The selectivity advantage:

Trametinib IC50 for MEK1: 0.7 nM

Next closest kinase: >100,000-fold selectivity

Compare to ATP-competitive inhibitors: often <10-fold selectivity

Alternative 2: Cryptic Pockets

What they are: Binding sites that don't exist in the ground-state structure but form transiently during protein dynamics.

Why they're valuable:

Not visible in crystal structures (which capture one conformation)

Unique to specific conformational states

Often druggable despite appearing "absent"

How cryptic pockets form:

Side chain movements expose buried cavities

Domain motions open transient channels

Loop movements create temporary binding sites

Ligand binding induces pocket formation (induced fit)

Detection methods:

Molecular dynamics: Simulate protein motion, analyze transient cavities

MSA subsampling: Alternative AlphaFold conformations

Ensemble docking: Screen against multiple structures

Fragment screening: Small molecules can "trap" transient states

Example: p38 MAPK

The DFG-out conformation creates an allosteric pocket:

DFG-in (active): No allosteric pocket visible

DFG-out (inactive): Large hydrophobic pocket opens

Type II inhibitors (e.g., sorafenib) bind this cryptic pocket

Much greater selectivity than Type I (ATP-competitive) inhibitors

Alternative 3: Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Sites

What they are: Interfaces where proteins contact each other, now targetable by small molecules.

Why they were considered "undruggable":

Large, flat interfaces (1000-2000 Ų)

No obvious pocket

Hot spots distributed across interface

Why that changed:

Hot spots (critical residues) contribute most binding energy

Small molecules can mimic hot spot interactions

Fragment-based approaches can find starting points

Macrocycles and peptide mimetics span larger areas

Success stories:

Drug | PPI Target | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

Venetoclax | BCL-2/BH3 | Mimics BH3 peptide binding |

Nutlins | MDM2/p53 | Blocks p53 binding groove |

BET inhibitors | BRD4/acetyl-lysine | Displaces histone binding |

The hot spot principle:

Only 5-10% of interface residues contribute >75% of binding energy. These "hot spots" are:

Often hydrophobic (Trp, Tyr, Phe)

Clustered spatially

Potentially druggable with small molecules

Alternative 4: Exosites and Peripheral Pockets

What they are: Binding sites adjacent to (but distinct from) the active site.

How they differ from allosteric sites:

Physically closer to active site

May partially overlap with substrate binding

Can provide selectivity without requiring conformational change

Example: Factor Xa exosite

Factor Xa has:

Active site: Serine protease catalytic triad (conserved across coagulation cascade)

S4 exosite: Adjacent pocket unique to Factor Xa

Drug strategy:

First-generation: Active site inhibitors (non-selective, bleeding risk)

Rivaroxaban: Extends into S4 pocket (selective for Factor Xa, safer)

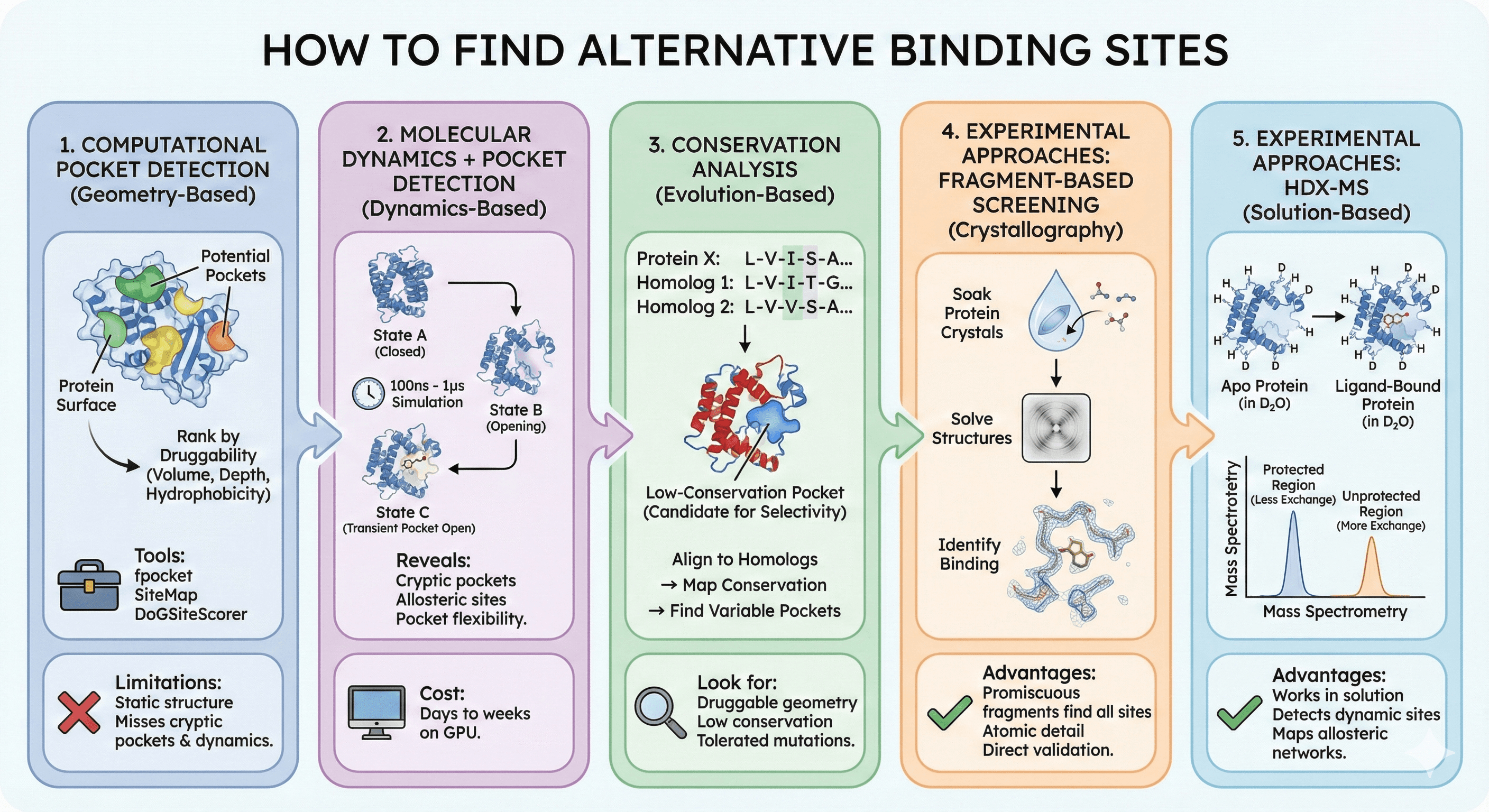

How to Find Alternative Binding Sites

Computational Pocket Detection

Geometry-based methods:

Scan protein surface for concave regions

Calculate pocket volume and depth

Rank by "druggability" (hydrophobicity, enclosure)

Tools:

fpocket: Fast pocket detection from structure

SiteMap: Commercial, predicts druggability

DoGSiteScorer: Machine learning-enhanced detection

Limitations:

Only detect pockets visible in the input structure

Miss cryptic pockets and conformational changes

Don't account for pocket dynamics

Molecular Dynamics + Pocket Detection

The approach:

Run MD simulation (100 ns - 1 μs)

Cluster conformations

Detect pockets in each cluster

Find pockets that appear transiently

What this reveals:

Cryptic pockets that open during dynamics

Allosteric sites that breathe

Flexibility of known pockets

Druggability of transient states

Computational cost: Days to weeks on GPU clusters

Conservation Analysis

The principle: Allosteric sites are less conserved than active sites.

The workflow:

Align protein to homologs

Map conservation onto structure

Find pockets in low-conservation regions

These are candidates for selective drug design

Tools:

ConSurf: Conservation mapping onto structure

BLAST + structure alignment: Manual analysis

Conservation scores from MSAs

What to look for:

Druggable pocket (geometry, hydrophobicity)

Low conservation in that pocket

Not required for folding (mutations tolerated)

Experimental Approaches

Fragment-based screening:

Soak protein crystals with fragment libraries (small, diverse molecules)

Solve structures

Find where fragments bind

Many fragments find allosteric sites and cryptic pockets

Advantages:

Fragments are promiscuous—they find all binding sites

X-ray crystallography provides atomic detail

Experimental validation of binding

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX-MS):

Expose protein to D2O with and without ligand

Measure which regions are protected from exchange

Protected regions indicate binding site

Advantages:

Works in solution (no crystallization)

Detects dynamic binding sites

Can map allosteric networks

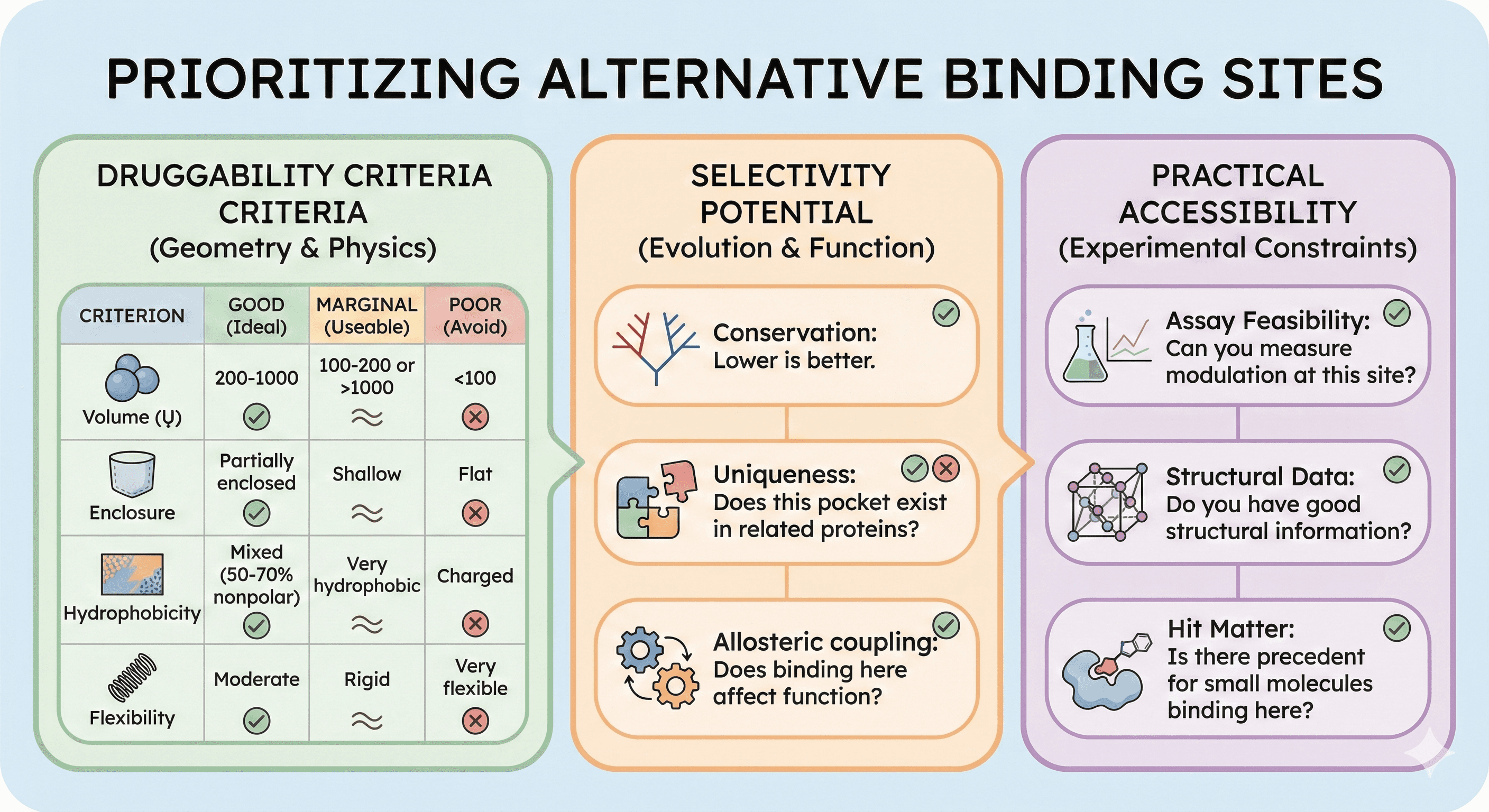

Prioritizing Alternative Sites

Not all pockets are druggable. Use these criteria to prioritize:

Druggability Criteria

Criterion | Good | Marginal | Poor |

|---|---|---|---|

Volume | 200-1000 ų | 100-200 Ų or >1000 ų | <100 ų |

Enclosure | Partially enclosed | Shallow | Flat |

Hydrophobicity | Mixed (50-70% nonpolar) | Very hydrophobic | Charged |

Flexibility | Moderate | Rigid | Very flexible |

Selectivity Potential

Score each pocket for selectivity advantage:

Conservation: Lower is better

Uniqueness: Does this pocket exist in related proteins?

Allosteric coupling: Does binding here affect function?

Practical Accessibility

Consider experimental constraints:

Assay feasibility: Can you measure modulation at this site?

Structural data: Do you have good structural information?

Hit matter: Is there precedent for small molecules binding here?

Case Study: From ATP Site Failure to Allosteric Success

The Challenge

Target: A kinase upregulated in cancer.

First attempt: ATP-competitive inhibitor

IC50: 5 nM against target

But: IC50 <100 nM against 23 related kinases

Clinical result: Dose-limiting toxicity from off-target effects

The Alternative Site Search

Step 1: Conservation analysis

Aligned target to 50 closest kinases

Mapped conservation onto structure

ATP pocket: 92% conserved (expected)

Helix αC region: 40% conserved (interesting)

Myristate pocket: 25% conserved (very interesting)

Step 2: Pocket detection

Ran fpocket on crystal structure

Found 6 putative binding sites

Site 3 overlapped with low-conservation region

Site 5 was a cryptic pocket (only in one crystal form)

Step 3: MD simulation

Ran 500 ns simulation

Site 5 opened transiently (30% of frames)

When open, it connected to the ATP site

Allosteric coupling predicted

The Solution

Strategy: Design molecule that binds Site 5 (cryptic pocket) and stabilizes inactive conformation.

Result:

New compound: IC50 12 nM for target

Selectivity: >1000-fold over all related kinases

Mechanism: Stabilizes inactive conformation, blocks activation

Clinical outcome:

Tolerated at therapeutic doses

No dose-limiting kinase-related toxicity

Proceeded to Phase II

The Lesson

The ATP pocket was a trap. It was obvious, druggable, and led to a potent compound—that was useless in humans. The real opportunity was hidden in a less conserved region that required computational analysis to identify.

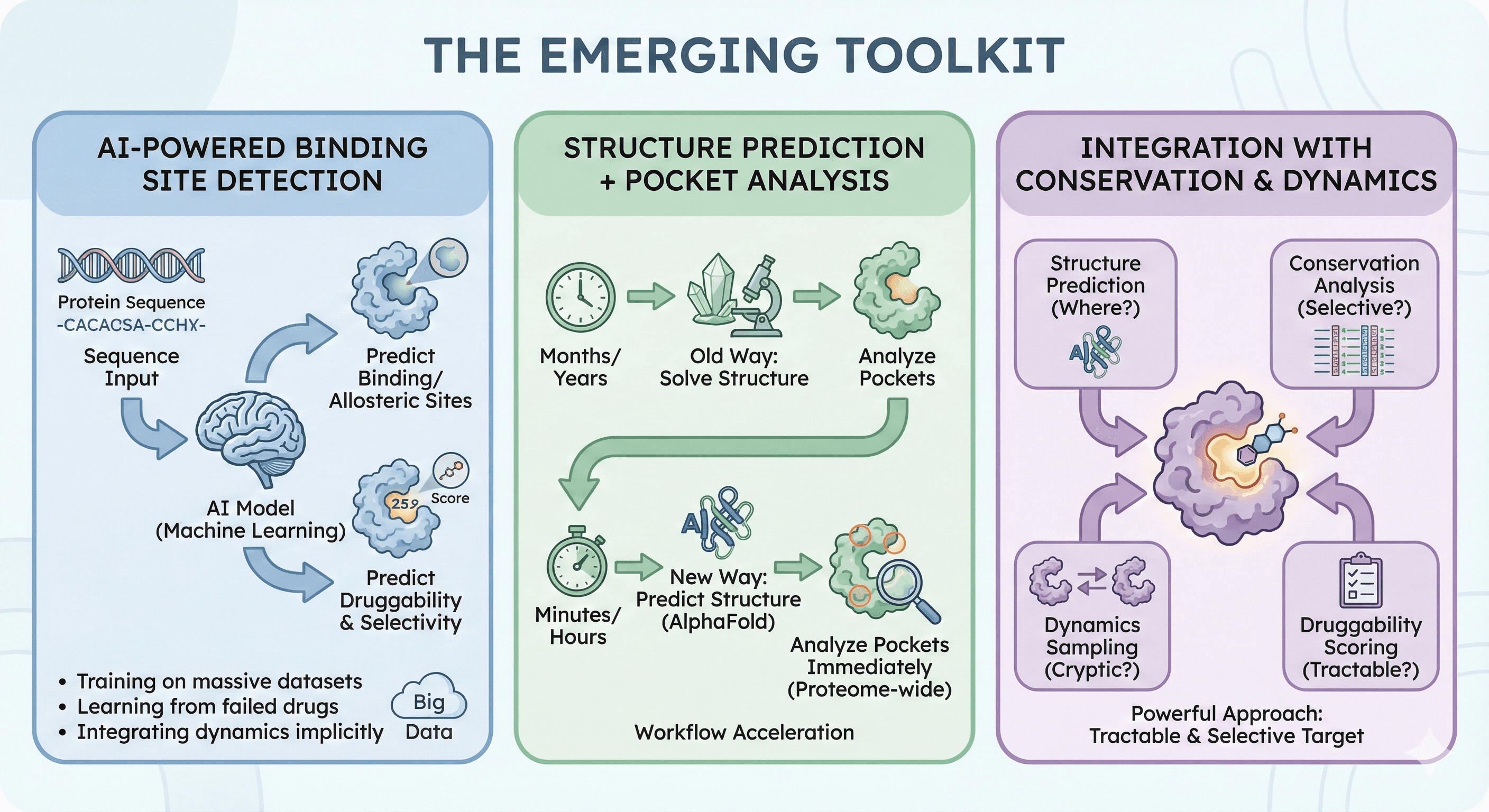

The Emerging Toolkit

AI-Powered Binding Site Detection

Modern machine learning approaches can:

Predict binding sites from sequence (no structure needed)

Identify likely allosteric sites

Predict druggability from learned features

Suggest modifications for selectivity

What's changing:

Training on massive datasets of protein-ligand interactions

Learning from failed drugs (what not to target)

Integrating dynamics implicitly through training data

Structure Prediction + Pocket Analysis

With AlphaFold:

Generate structure in seconds

Analyze for binding sites immediately

Run on the proteome, not just solved structures

The workflow acceleration:

Old way: Solve structure (months/years) → analyze pockets

New way: Predict structure (minutes) → analyze pockets (hours)

Integration with Conservation and Dynamics

The most powerful approach combines:

Structure prediction: Where are the pockets?

Conservation analysis: Which pockets are selective?

Dynamics sampling: What cryptic pockets exist?

Druggability scoring: Which pockets are tractable?

Practical Workflow: Finding Your Alternative Site

Phase 1: Initial Pocket Survey (Day 1)

Get or predict structure

PDB structure if available

AlphaFold prediction if not

Run pocket detection

fpocket or equivalent

List all detected pockets

Map conservation

Align to homologs

Calculate per-residue conservation

Overlay on pockets

Preliminary ranking

Active site: Known, but likely non-selective

Alternative pockets: Ranked by druggability + low conservation

Phase 2: Deeper Analysis (Week 1)

Dynamics (if resources allow)

MD simulation (100 ns minimum)

Cluster conformations

Detect cryptic pockets

Allosteric network analysis

Which residues couple to active site?

Do any alternative pockets include coupled residues?

Literature check

Any known allosteric modulators?

Fragment screening data available?

Mutations in this region affect function?

Phase 3: Experimental Validation (Month 1)

Fragment screening

If you can produce protein: X-ray crystallography with fragments

If not: SPR or DSF with fragment libraries

Functional assay

Can you detect allosteric modulation?

What's the direction (inhibition, activation)?

Hit validation

Confirm binding at alternative site

Measure selectivity improvement

The Bottom Line

Active sites are the obvious targets—and that's the problem. Evolution has optimized them for function, making them nearly identical across protein families. Drugs targeting active sites are potent but non-selective.

The alternative sites (allosteric pockets, cryptic cavities, PPI interfaces) are less obvious but offer the selectivity that active sites can't provide:

Site Type | Conservation | Selectivity Potential | Druggability |

|---|---|---|---|

Active site | Very high | Low | High |

Allosteric site | Moderate | High | Moderate |

Cryptic pocket | Low | Very high | Variable |

PPI interface | Low | Very high | Challenging |

The drug discovery field is shifting from "find the active site, design an inhibitor" to "find the selective site, even if it's not obvious."

Computational Binding Site Identification

For researchers looking to explore alternative binding sites, platforms like Orbion can identify binding sites beyond the obvious active site location. The platform's binding site prediction:

Detects multiple putative binding sites across the protein surface

Maps predictions to the 3D structure for visualization

Provides a starting point for allosteric and alternative site exploration

Combined with conservation analysis and experimental validation, this enables a rational workflow for escaping the selectivity trap that active site targeting inevitably creates.

References

Manning G, et al. (2002). The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science, 298(5600):1912-1934. Link

Klaeger S, et al. (2017). The target landscape of clinical kinase drugs. Science, 358(6367):eaan4368. Link

Druker BJ, et al. (2001). Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 344(14):1031-1037. Link

Wu P, et al. (2015). Allosteric small-molecule kinase inhibitors. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 156:59-68. Link

Nussinov R & Tsai CJ. (2013). Allostery in disease and in drug discovery. Cell, 153(2):293-305. Link

Le Guilloux V, et al. (2009). Fpocket: an open source platform for ligand pocket detection. BMC Bioinformatics, 10:168. Link

Fang Z, et al. (2015). Strategies for the selective regulation of kinases with allosteric modulators. Nature Chemical Biology, 11:452-460. Link