Blog

The Hidden Link Between Disorder, Aggregation, and Failed Purifications

Jan 23, 2026

Your protein looked perfect after affinity chromatography. Eluted as a single peak. Then you concentrated it for crystallization trials, walked away for lunch, and came back to a cloudy tube. By the time you ran the gel filtration, half your protein had vanished into the void volume—aggregated, irreversibly.

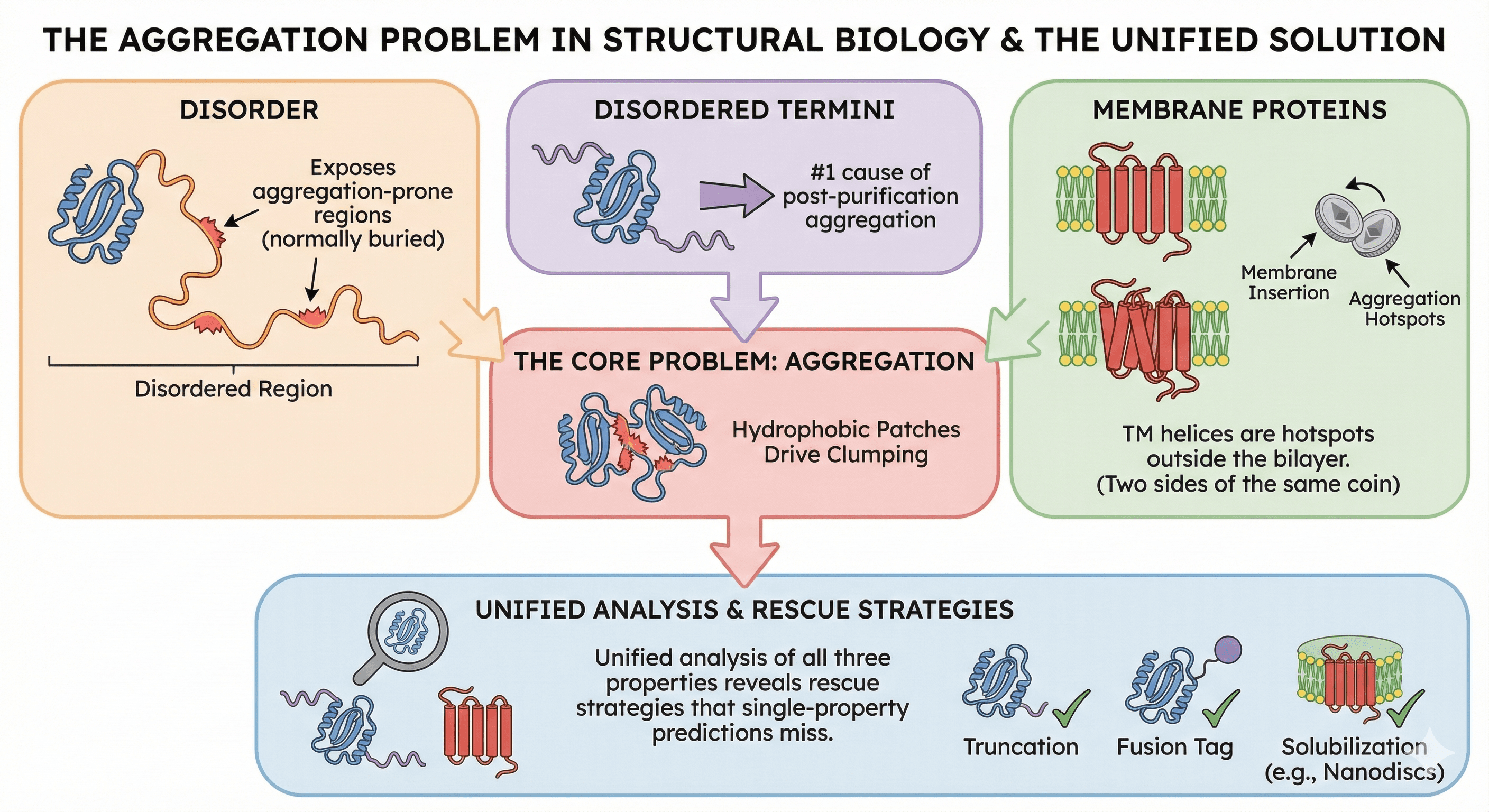

The frustrating part: this was predictable. The aggregation wasn't random. It was written into the sequence, hidden in the interplay between three properties that most researchers analyze separately but are fundamentally connected: disorder, aggregation propensity, and membrane topology.

Key Takeaways

Disorder exposes aggregation-prone regions that are normally buried in folded proteins

Disordered termini are the #1 cause of post-purification aggregation

Membrane proteins misbehave because their hydrophobic TM helices are aggregation hotspots outside the bilayer

The same hydrophobic patches that drive aggregation also drive membrane insertion—they're two sides of the same coin

Unified analysis of all three properties reveals rescue strategies that single-property predictions miss

The Hidden Connection

Most prediction tools treat disorder, aggregation, and membrane topology as separate problems:

Use IUPred for disorder

Use AGGRESCAN for aggregation

Use TMHMM for topology

But in the biophysics of your protein, these aren't separate. They're deeply connected through one principle: hydrophobicity and its exposure to water.

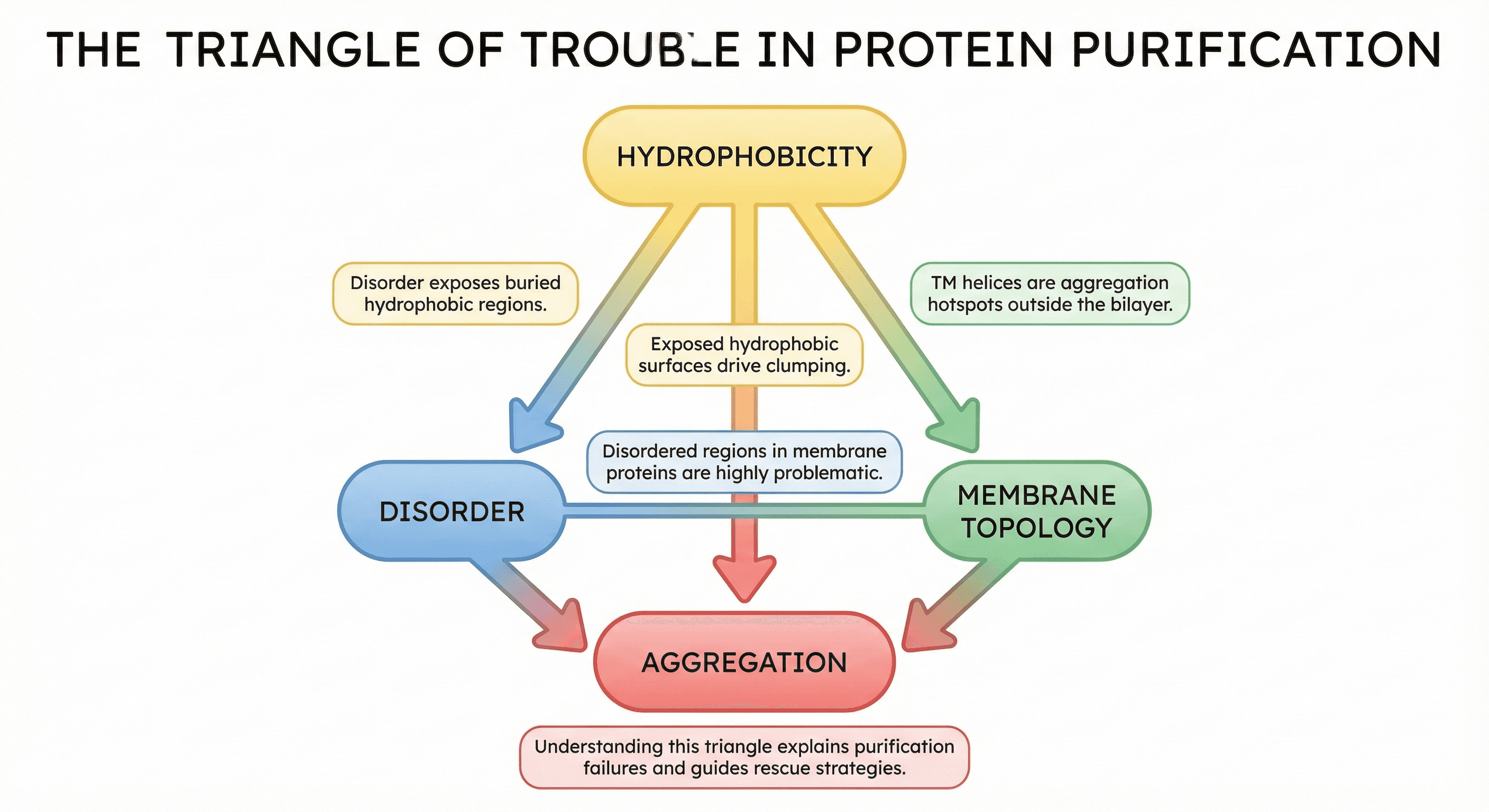

The Triangle of Trouble

The connections:

Disorder exposes hydrophobic regions → aggregation

Membrane proteins have hydrophobic TM helices → aggregate when extracted from membrane

Disordered regions in membrane proteins → especially problematic

Understanding this triangle explains why your purification failed—and how to fix it.

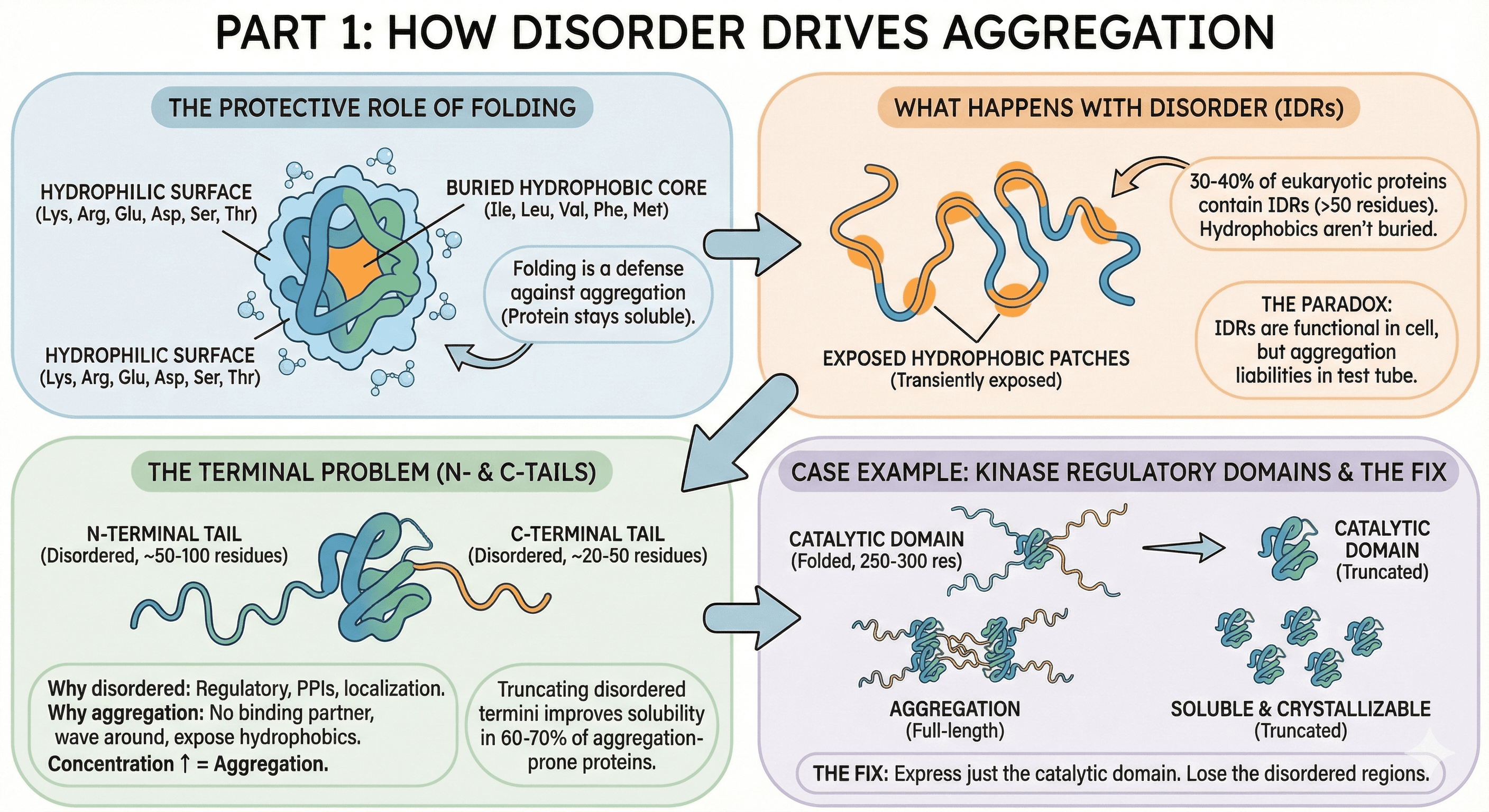

Part 1: How Disorder Drives Aggregation

The Protective Role of Folding

In a well-folded protein:

Hydrophobic residues (Ile, Leu, Val, Phe, Met) are buried in the core

The surface is mostly hydrophilic (Lys, Arg, Glu, Asp, Ser, Thr)

Water interacts with the hydrophilic surface

Protein stays soluble

Folding is a defense mechanism against aggregation.

What Happens When Regions Are Disordered

About 30-40% of eukaryotic proteins contain significant disordered regions (>50 residues), and disorder is present in some form in ~70% of all proteins (Dunker et al., 2008). These intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) don't have stable tertiary structure, which means:

Hydrophobic residues aren't stably buried

They transiently expose to solvent

Exposed hydrophobic patches stick to each other

Aggregation nucleates

The paradox: IDRs are often functional in the cell (protein-protein interactions, signaling, localization). But in a test tube, without their binding partners, they become aggregation liabilities. IDPs are notably overrepresented in protein aggregates associated with neurodegenerative diseases (Vendruscolo, 2022).

The Terminal Problem

The most common disorder-driven aggregation involves N- and C-terminal tails:

Why termini are often disordered:

Termini are frequently regulatory regions

They mediate protein-protein interactions

They contain localization signals

They're evolutionarily flexible

Why this causes aggregation:

No binding partner in your purification buffer

Disordered termini wave around, exposing hydrophobic patches

Concentration increases → more collisions → aggregation

The data:

30-40% of eukaryotic proteins have disordered termini (>20 residues)

Truncating disordered termini improves solubility in 60-70% of aggregation-prone proteins

This is the single most effective intervention for post-purification aggregation

Case Example: Kinase Regulatory Domains

Many kinases have:

Disordered N-terminal region (50-100 residues)

Well-folded catalytic domain (250-300 residues)

Disordered C-terminal tail (20-50 residues)

In the cell:

N-terminus binds regulatory partners

C-terminus contains phosphorylation sites for regulation

Both are functional

In your purification:

N-terminus has no partners → aggregates

C-terminus has no phosphatases → aggregates

Catalytic domain is dragged along

The fix:

Express just the catalytic domain

Lose the disordered regions

Gain a soluble, crystallizable protein

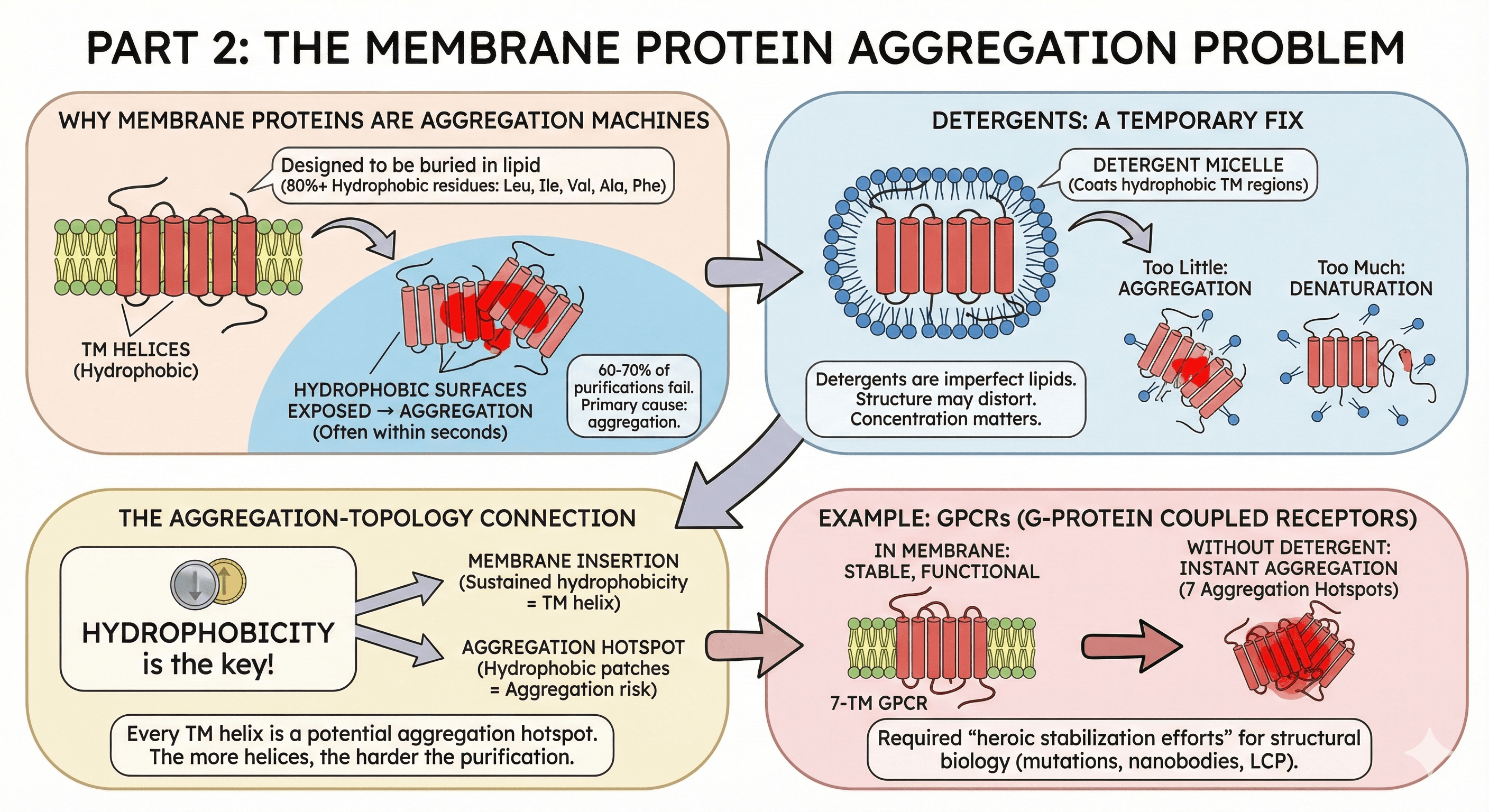

Part 2: The Membrane Protein Aggregation Problem

Why Membrane Proteins Are Aggregation Machines

Transmembrane (TM) helices have a specific job: span the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer. To do this, they're composed almost entirely of hydrophobic residues.

A typical TM helix:

20-25 residues long

80%+ hydrophobic (Leu, Ile, Val, Ala, Phe)

Designed to be buried in lipid

What happens during purification:

You lyse cells → membrane is disrupted

TM helices are exposed to aqueous buffer

Hydrophobic surfaces find each other

Aggregation—often within seconds

The numbers:

60-70% of membrane protein purifications fail

Primary cause: aggregation during detergent extraction

GPCRs, ion channels, transporters are all affected

Detergents: A Temporary Fix

Detergents solubilize membrane proteins by:

Coating the hydrophobic TM regions

Creating a micelle that mimics the membrane

Keeping the protein in solution

But detergents are imperfect:

They're not lipids—structure may distort

They don't stabilize the same way membranes do

Concentration matters: too little → aggregation; too much → denaturation

Many proteins are unstable even in optimal detergent

The Aggregation-Topology Connection

Here's where it gets interesting: the same residues that make a helix "transmembrane" make it "aggregation-prone."

Prediction tools use hydrophobicity to identify:

TM helices (sustained hydrophobicity = membrane span)

Aggregation hotspots (hydrophobic patches = aggregation risk)

They're detecting the same underlying property from different angles.

This means:

Every TM helix is a potential aggregation hotspot

Membrane proteins have multiple aggregation hotspots (one per TM helix)

The more TM helices, the harder the purification

Example: GPCRs

G-protein coupled receptors have 7 TM helices = 7 aggregation hotspots:

In membrane: stable, functional receptor

In detergent: marginally stable, activity decays over hours

Without detergent: instant aggregation

This is why GPCR structural biology required heroic stabilization efforts (thermostabilizing mutations, nanobody stabilization, lipidic cubic phase crystallization).

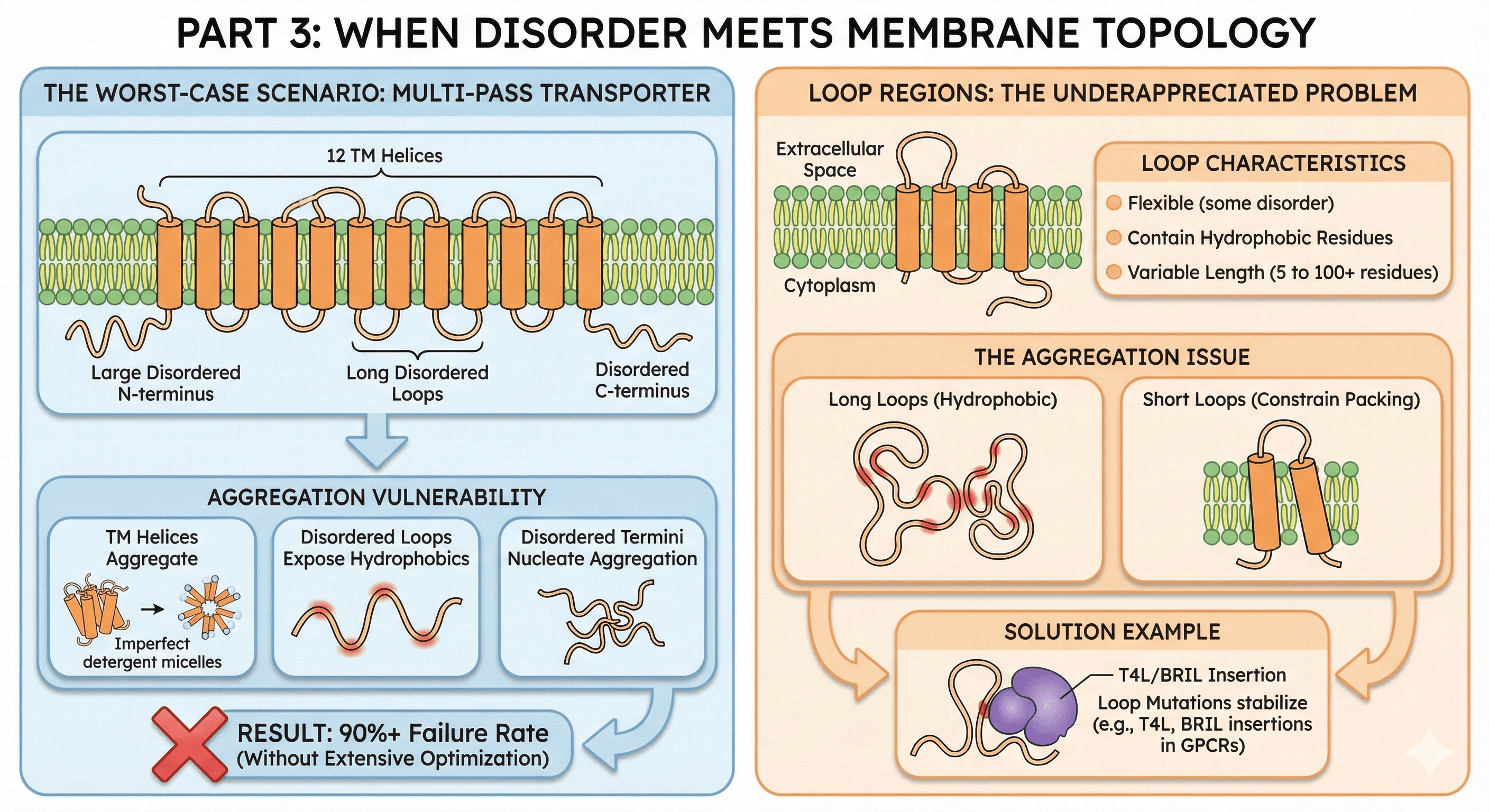

Part 3: When Disorder Meets Membrane Topology

The Worst-Case Scenario

Some proteins have both:

Transmembrane topology

Disordered cytoplasmic loops or termini

Example: Multi-pass transporters

A typical transporter might have:

12 TM helices

Large disordered N-terminus (regulatory)

Long disordered loops between TM helices

Disordered C-terminus

The aggregation vulnerability:

TM helices aggregate if detergent coverage is imperfect

Disordered loops don't fold → expose hydrophobic residues

Disordered termini flail around → nucleate aggregation

Multiple failure modes compound

Result: 90%+ failure rate without extensive optimization

Loop Regions: The Underappreciated Problem

Between TM helices, membrane proteins have loops that face either:

Extracellular space

Cytoplasm

Loop characteristics:

Often flexible (some disorder)

May contain hydrophobic residues (for partner binding or membrane association)

Variable length (from 5 to 100+ residues)

The aggregation issue:

Long loops with hydrophobic character aggregate

Short loops constrain TM helix packing → destabilize the fold

Loop mutations often designed to stabilize (T4L, BRIL insertions in GPCRs)

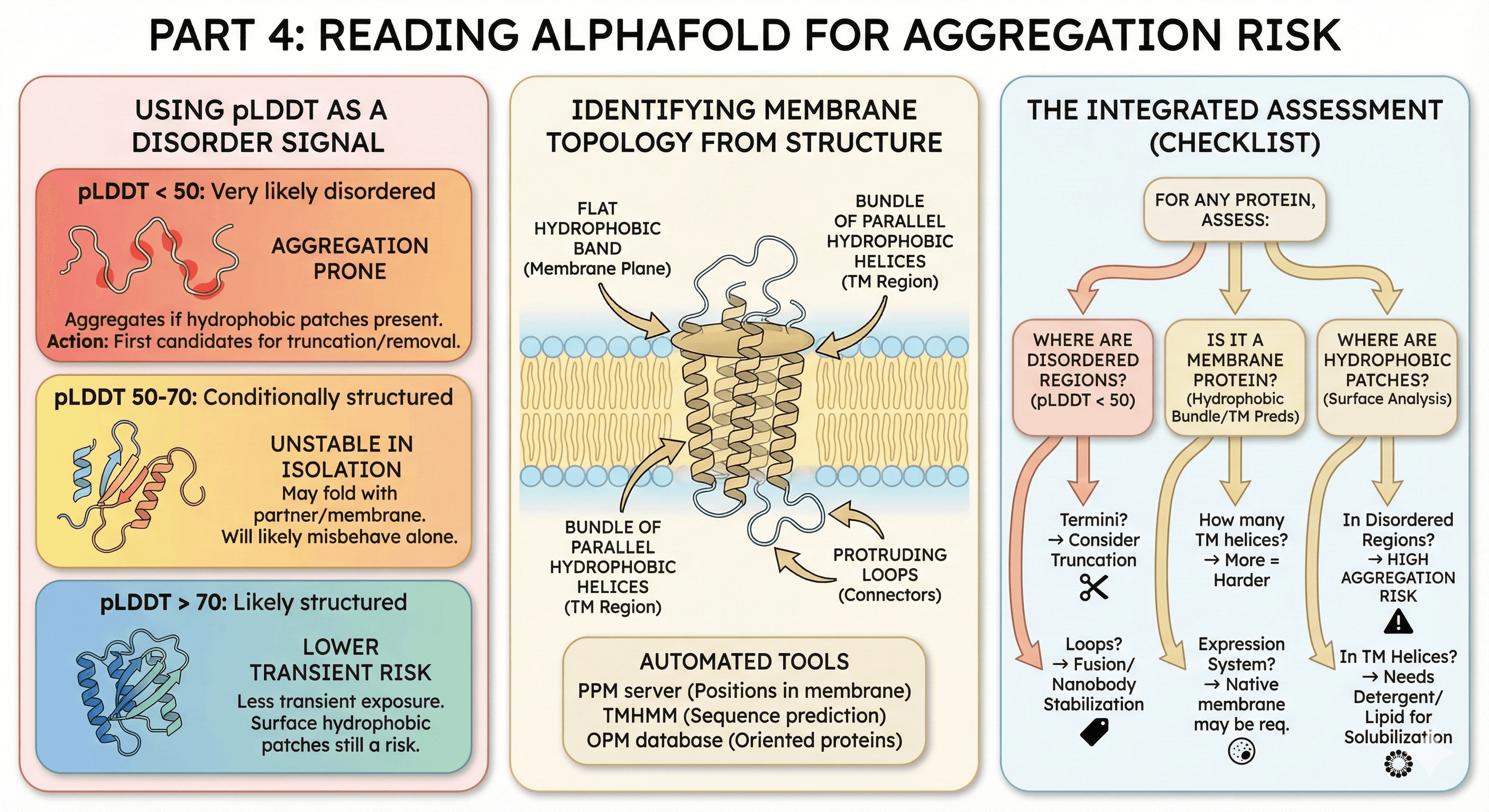

Part 4: Reading AlphaFold for Aggregation Risk

AlphaFold doesn't predict aggregation directly, but it tells you a lot about disorder and topology—and now you know these connect to aggregation.

Using pLDDT as a Disorder Signal

pLDDT < 50: Very likely disordered

These regions will aggregate in vitro if they contain hydrophobic patches

First candidates for truncation or removal

pLDDT 50-70: Conditionally structured

May fold with binding partner

May be stable in membrane context

Will likely misbehave in isolation

pLDDT > 70: Likely structured

Not necessarily aggregation-proof (surface hydrophobic patches still matter)

But less likely to expose hydrophobic residues transiently

Identifying Membrane Topology from Structure

AlphaFold predicts 3D structure, but you need to infer:

Which helices are transmembrane

Where the membrane boundaries are

Which loops are intra- vs extracellular

Visual clues:

Bundle of parallel hydrophobic helices = TM region

Flat "band" of hydrophobic residues = membrane plane

Loops protruding from bundle = connecting loops

Automated tools:

PPM server (positions protein in membrane)

TMHMM on sequence (predicts TM helices)

OPM database (oriented proteins in membrane)

The Integrated Assessment

For any protein, assess:

Where are the disordered regions? (pLDDT < 50)

Termini? → Consider truncation

Loops? → May need fusion proteins or nanobody stabilization

Is it a membrane protein? (Hydrophobic helix bundle, TM predictions)

How many TM helices? → More = harder

What expression system? → Native membrane may be required

Where are the hydrophobic patches? (Surface analysis)

In disordered regions? → High aggregation risk

In TM helices? → Need detergent/lipid for solubilization

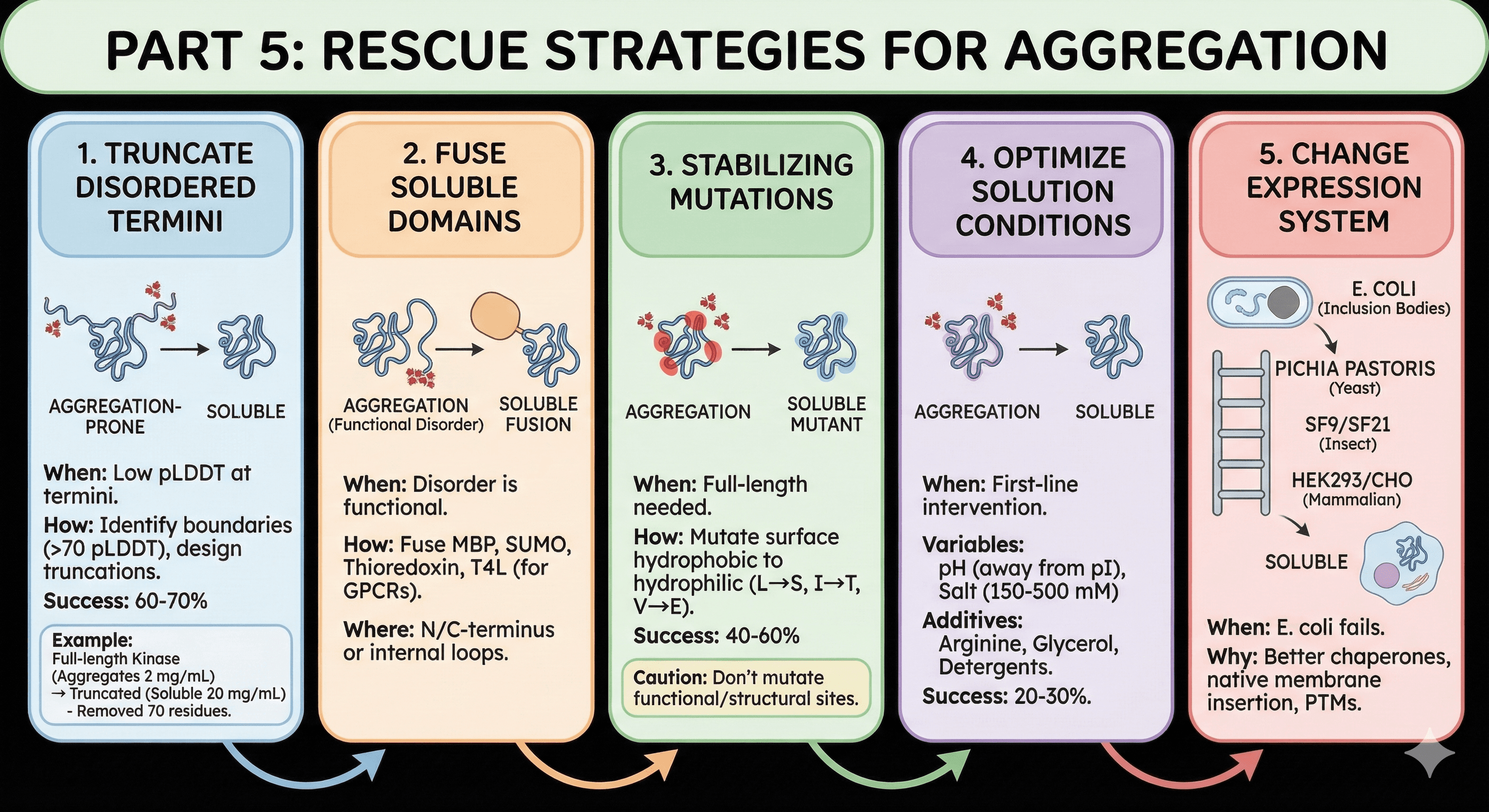

Part 5: Rescue Strategies

Strategy 1: Truncate Disordered Termini

When to use: pLDDT shows low-confidence termini

How to do it:

Identify disorder boundaries (where pLDDT rises above 70)

Design constructs that start/end at structured regions

Make 2-3 truncations at different boundaries

Test expression and solubility

Success rate: 60-70% of aggregation-prone proteins become soluble with terminal truncation

Example:

Full-length kinase (1-450): Aggregates at 2 mg/mL

Truncated kinase (51-420): Soluble at 20 mg/mL

Truncated 70 disordered residues, removed 2 aggregation hotspots

Strategy 2: Fuse Soluble Domains to Mask Aggregation

When to use: Disordered regions are functionally required

Common fusions:

MBP (maltose binding protein): Highly soluble, masks hydrophobic patches

SUMO: Improves folding, clean cleavage

Thioredoxin: Good for small proteins with aggregation issues

T4 Lysozyme (for GPCRs): Stabilizes TM helices by replacing flexible loops

Where to fuse:

N-terminus: Standard, usually least disruptive

C-terminus: If N-terminus is functionally important

Internal (loop replacement): For membrane proteins, replaces disordered loops

Strategy 3: Stabilizing Mutations

When to use: You need the full-length protein but it aggregates

Target selection:

Identify surface hydrophobic residues

Prioritize those in or near disordered regions

Mutate to hydrophilic residues (L→S, I→T, V→E)

Caution:

Don't mutate functional residues

Don't destabilize the fold (check ΔΔG)

Don't remove essential PTM sites

Success rate: 40-60% improvement with 2-3 mutations

Strategy 4: Optimize Solution Conditions

When to use: First-line intervention while planning construct redesign

Variables to screen:

pH: 0.5-1 unit away from pI (reduces aggregation)

Salt: 150-500 mM (increases ionic strength, reduces non-specific interactions)

Additives:

Arginine (100-500 mM): Disrupts hydrophobic interactions

Glycerol (10-20%): Stabilizes native state

Detergents (0.01-0.1%): For membrane proteins

Success rate: 20-30% of aggregating proteins can be rescued with buffer optimization alone

Strategy 5: Change Expression System

When to use: E. coli produces inclusion bodies despite optimization

The expression ladder:

E. coli: If this fails...

Pichia pastoris (yeast): Slower folding, eukaryotic chaperones

Sf9/Sf21 (insect): Better membrane protein handling

HEK293/CHO (mammalian): Native-like folding environment

Why switching helps:

Eukaryotic cells have better chaperone machinery

Membrane protein insertion is native

PTMs that aid folding are present

Case Study: Rescuing a Triple-Threat Protein

The Target

Human transporter protein:

12 TM helices

80-residue disordered N-terminus

Long disordered loop between TM6 and TM7

Critical for drug transport—needed for pharmacology studies

Initial Attempt

Expression: Sf9 insect cells Purification: DDM extraction, His-tag purification Result: Protein extracted, but aggregated within 4 hours at 4°C

Diagnosis

Analysis revealed:

Disorder: N-terminus (1-80) and loop (residues 320-380) show pLDDT < 40

Aggregation hotspots: Both disordered regions contain hydrophobic patches

TM instability: 12 TM helices require constant detergent coverage

The triple threat: Disorder + membrane topology + aggregation propensity

The Solution

Step 1: Truncate N-terminus

Removed residues 1-75

Kept 5 residues before first TM helix

Step 2: Replace disordered loop

Inserted T4 lysozyme (T4L) between TM6 and TM7

Rigid insertion stabilizes TM packing

Standard GPCR engineering strategy applied to transporter

Step 3: Optimize detergent

DDM → LMNG (longer chain, better coverage)

Added CHS (cholesterol hemisuccinate) for membrane stability

Step 4: Add nanobody

Raised nanobody against stable conformation

Nanobody binding further stabilizes the fold

The Result

Before: 4-hour stability, aggregates at 2 mg/mL

After: 48-hour stability, soluble at 5 mg/mL

Cryo-EM structure: Solved at 3.2 Å resolution

Key insight: All three problems (disorder, topology, aggregation) were addressed together. Fixing only one wouldn't have worked.

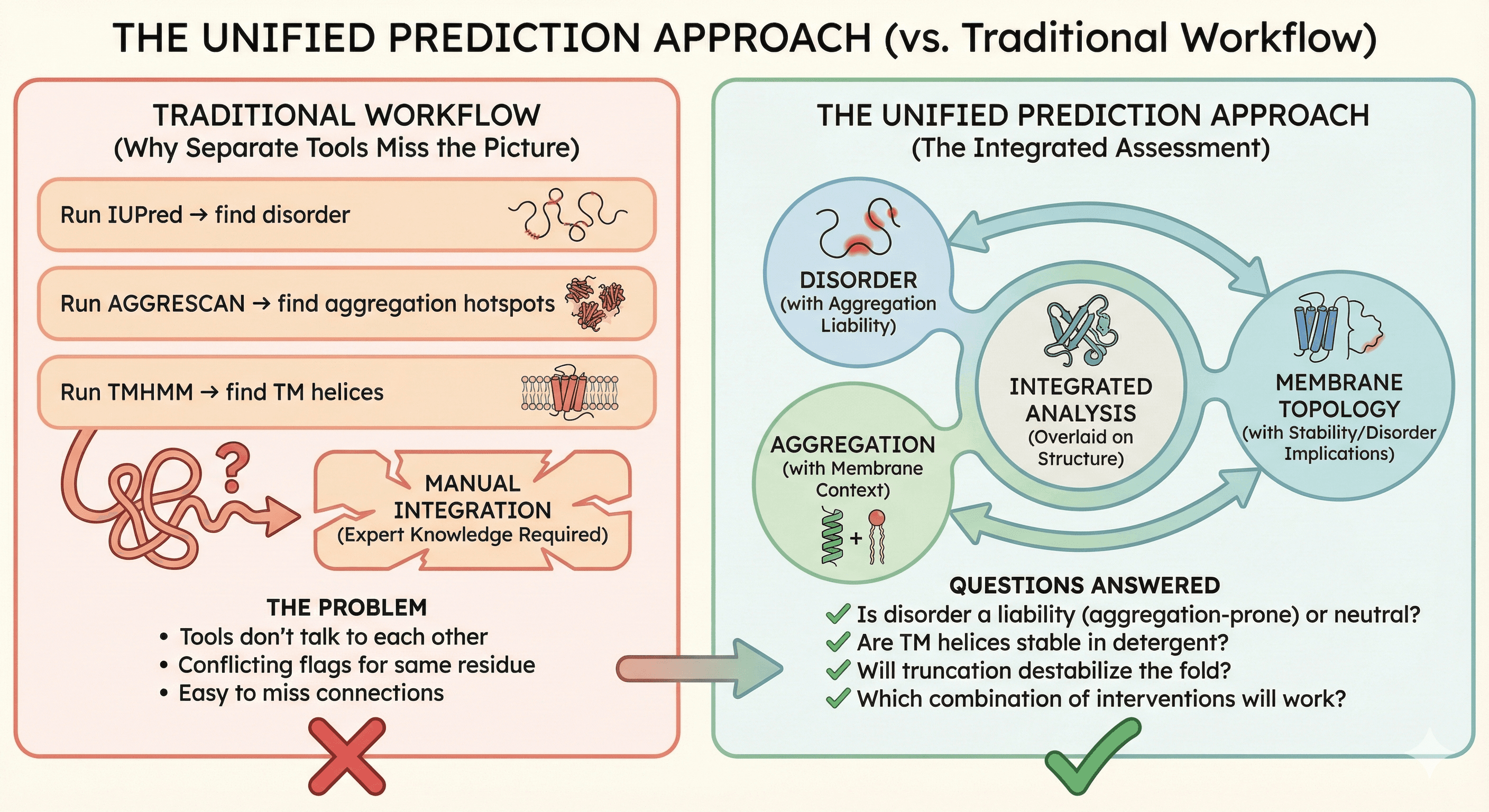

The Unified Prediction Approach

Why Separate Tools Miss the Picture

Traditional workflow:

Run IUPred → find disorder

Run AGGRESCAN → find aggregation hotspots

Run TMHMM → find TM helices

Try to integrate manually

The problem:

Tools don't talk to each other

Same residue might be flagged differently by each tool

Integration requires expert knowledge

Easy to miss connections

The Integrated Assessment

What you actually need:

Disorder prediction that considers aggregation consequences

Aggregation prediction that accounts for membrane context

Membrane topology with disorder and stability implications

All three overlaid on the structure

Questions an integrated analysis answers:

Is this disordered region a liability (aggregation-prone) or neutral (hydrophilic)?

Are these TM helices stable in detergent, or do they need specific lipids?

Will truncating this terminus destabilize the fold?

Which combination of interventions will work?

Practical Decision Tree

The Bottom Line

Disorder, aggregation, and membrane topology aren't three separate problems. They're manifestations of the same underlying biophysics: hydrophobic residues and their exposure to water.

Property | What It Means | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

Disorder | No stable structure | Hydrophobic residues transiently exposed |

Aggregation propensity | Hydrophobic surface patches | Proteins stick to each other |

Membrane topology | Hydrophobic TM helices | Aggregate outside membrane |

The unified principle: Anything that exposes hydrophobic residues to water is an aggregation risk.

Understanding this connection transforms troubleshooting:

Not "my protein is disordered" but "my protein exposes aggregation hotspots"

Not "my protein needs detergent" but "my TM helices aggregate without membrane mimetics"

Not "three separate problems" but "one problem with three manifestations"

Unified Analysis for Aggregation Rescue

For researchers dealing with aggregation-prone proteins, platforms like Orbion provide integrated analysis of disorder, aggregation propensity, and membrane topology from a single prediction. This unified view reveals:

Which disordered regions are actually aggregation liabilities

How membrane topology contributes to purification difficulty

Where to truncate, mutate, or fuse to rescue your protein

What expression system and purification conditions to prioritize

The goal is to see the connections between these properties before you start purifying—so you can design constructs that avoid the aggregation trap entirely, rather than troubleshooting it for months afterward.

References

Dunker AK, et al. (2008). Function and structure of inherently disordered proteins. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 18(6):756-764. PMC2443096

Vendruscolo M, et al. (2022). Intrinsically disordered proteins identified in the aggregate proteome serve as biomarkers of neurodegeneration. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15:780567. PMC8748380

Uversky VN. (2013). Intrinsic disorder-based protein interactions and their modulators. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 19(23):4191-4213. Link

Chiti F & Dobson CM. (2017). Protein Misfolding, Amyloid Formation, and Human Disease: A Summary of Progress Over the Last Decade. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 86:27-68. Link

Krogh A, et al. (2001). Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. Journal of Molecular Biology, 305(3):567-580. Link

Fernandez-Escamilla AM, et al. (2004). Prediction of sequence-dependent and mutational effects on the aggregation of peptides and proteins. Nature Biotechnology, 22(10):1302-1306. Link