Blog

When to Give Up on a Protein Target

Feb 13, 2026

You've spent six months on this protein. Twelve expression constructs. Three expression systems. Refolding from inclusion bodies. Co-expression with chaperones. Insect cells. Mammalian cells. You have 200 µg of mostly aggregated material that loses activity overnight. Your PI asks if you should try one more thing. Your gut says to walk away. But how do you know when enough is enough?

There's no universal answer, but there are rational criteria for deciding when a protein target has become a sunk cost rather than a future success.

Key Takeaways

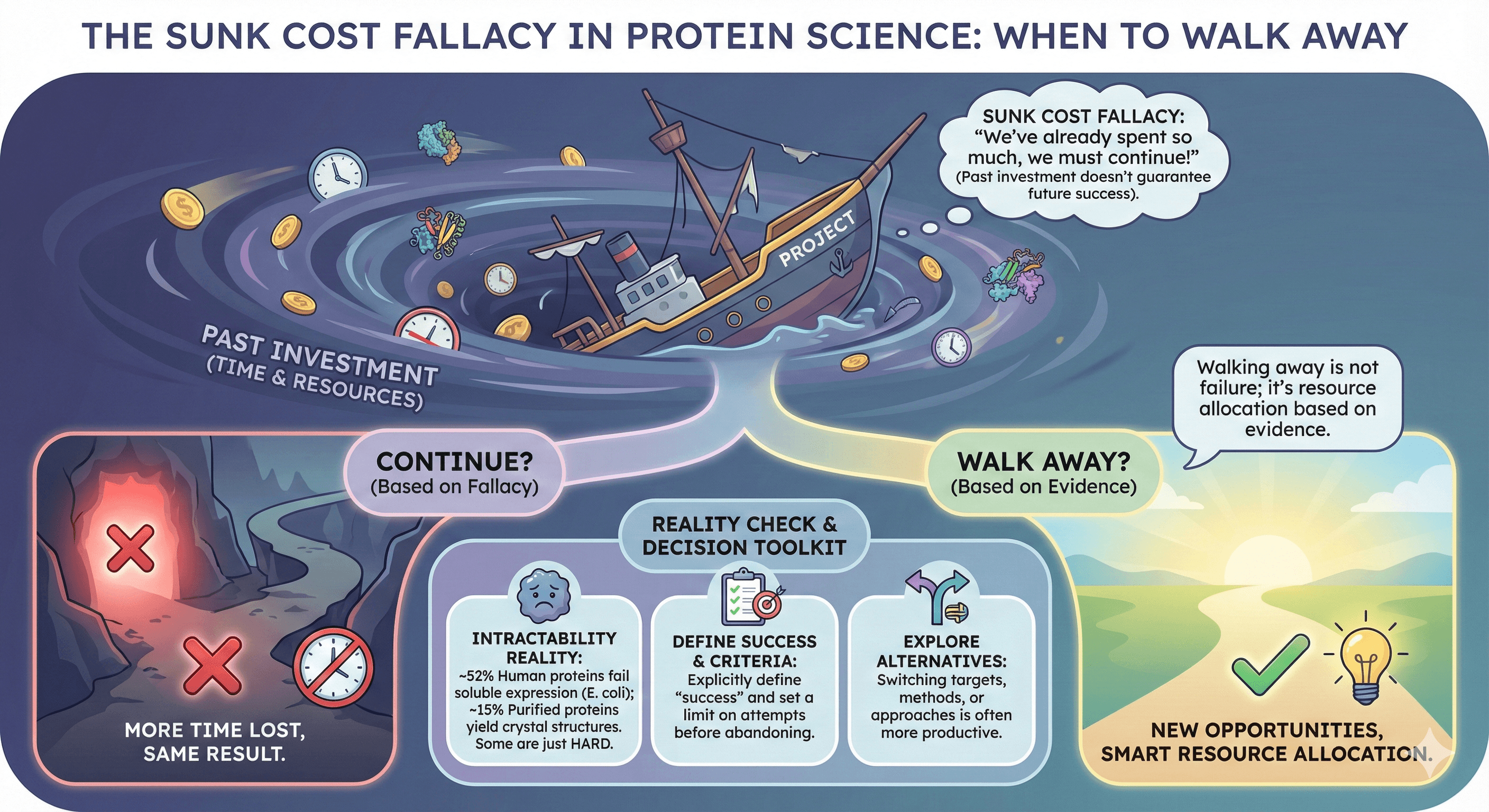

Sunk cost fallacy is real in protein science: The time already invested doesn't make future success more likely

Some proteins are genuinely intractable: ~52% of human proteins fail to express solubly in E. coli; ~15% of purified proteins yield crystal structures

Decision criteria should be explicit: Define what "success" looks like and how many attempts justify abandonment

Alternatives exist: Switching targets, methods, or approaches may be more productive than continuing

Walking away is not failure: It's resource allocation based on evidence

The Psychology of Persistence

The Sunk Cost Problem

The more you invest in a target, the harder it is to abandon it:

"I've spent six months on this—I can't give up now"

"We've already ordered so many constructs"

"The preliminary data was so promising"

"If we just try one more thing..."

This is the sunk cost fallacy: past investment doesn't change the probability of future success. A protein that hasn't expressed in 12 attempts isn't more likely to express on attempt 13 just because you've tried 12 times.

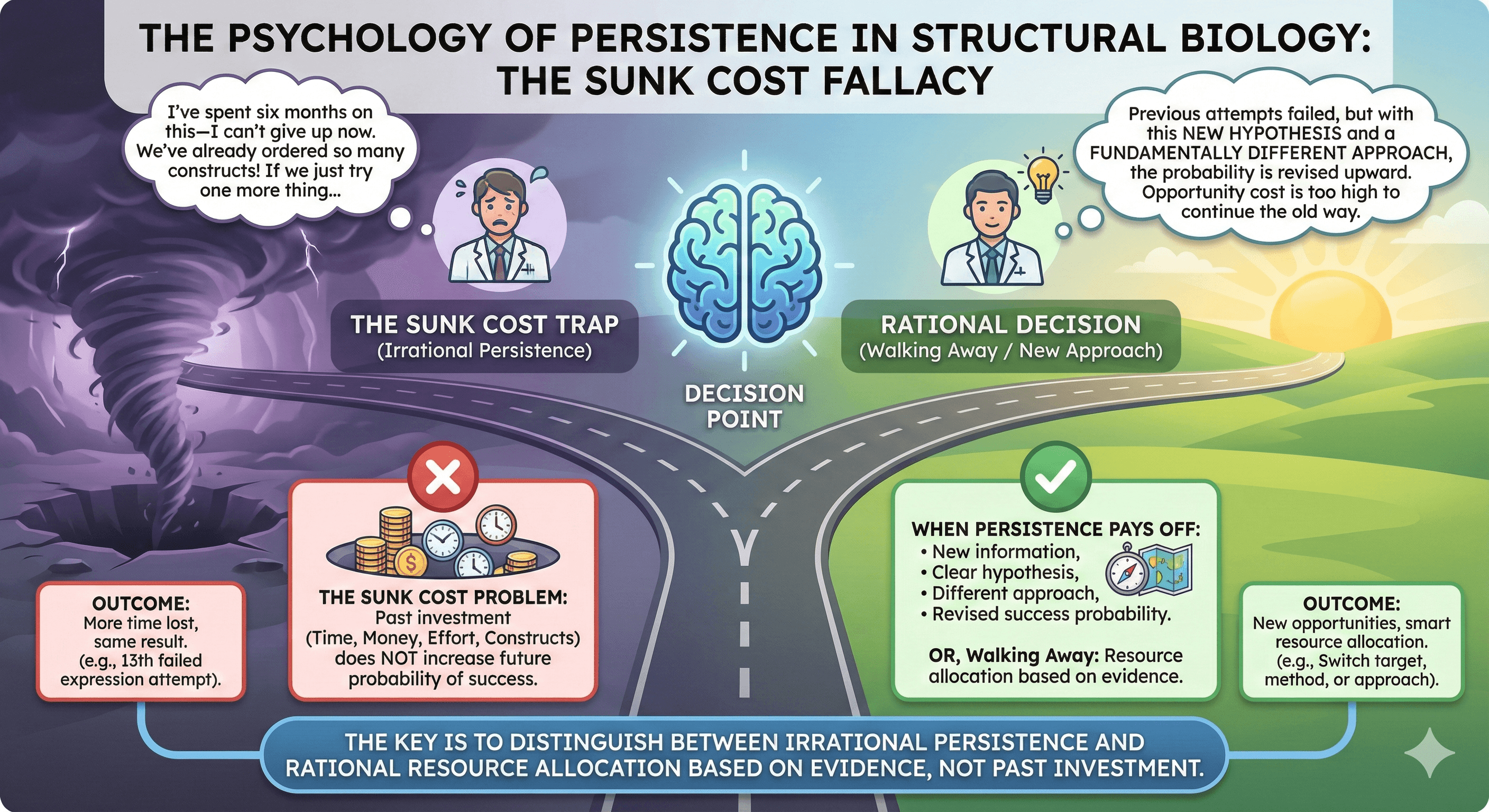

When Persistence Pays Off vs. When It Doesn't

Persistence makes sense when:

Each attempt provides new information

There's a clear hypothesis for why previous attempts failed

The next attempt tests something fundamentally different

Success probability is revised upward based on new data

Persistence is irrational when:

You're repeating similar approaches hoping for different results

There's no hypothesis—just "maybe this will work"

Success probability hasn't changed despite new information

Opportunity cost of continuing exceeds potential benefit

The Numbers: What Are Realistic Success Rates?

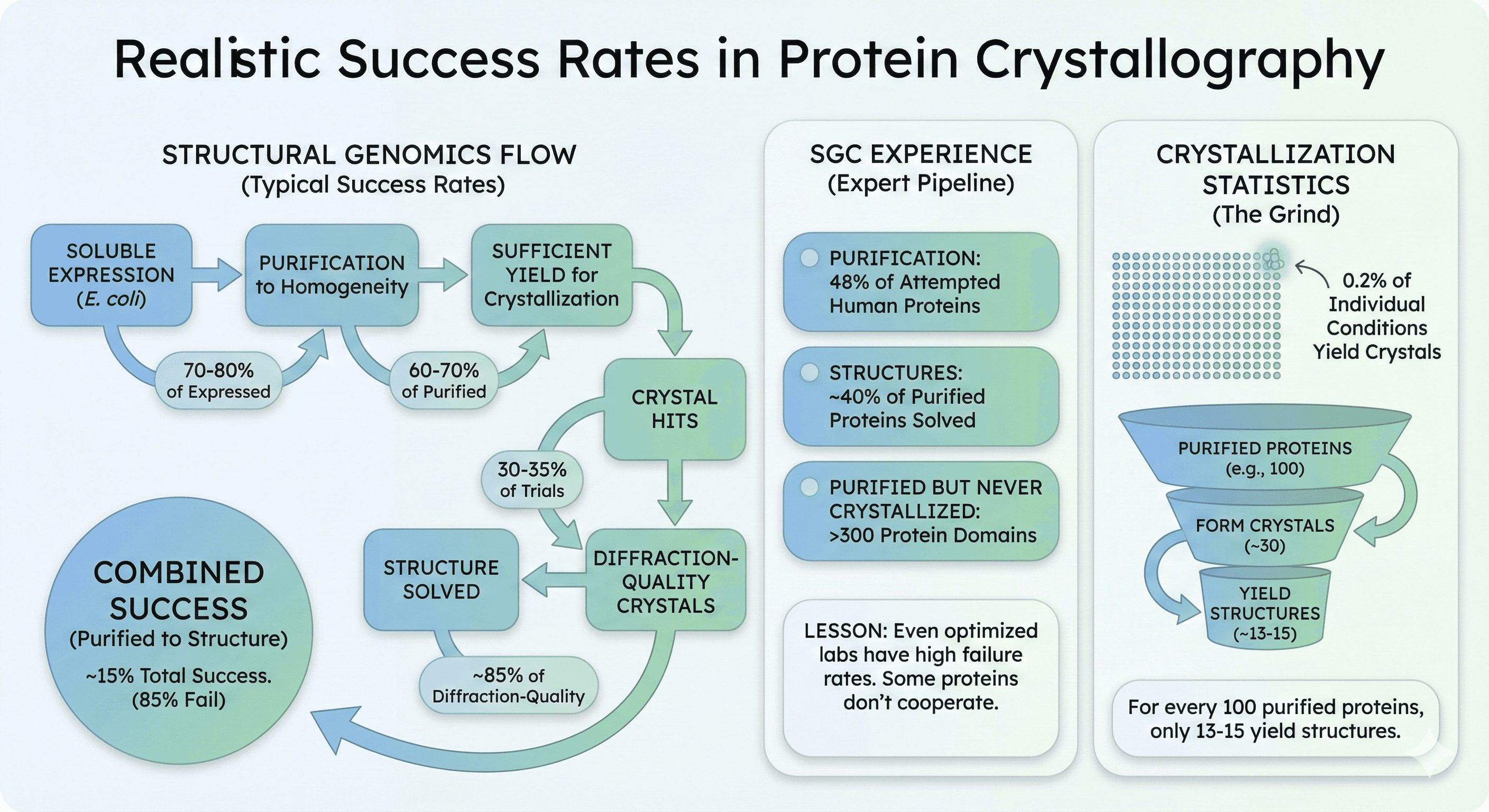

Expression Success Rates

From structural genomics consortia data:

Stage | Typical Success Rate |

|---|---|

Soluble expression (E. coli) | 40-50% |

Purification to homogeneity | 70-80% of expressed |

Sufficient yield for crystallization | 60-70% of purified |

Crystal hits | 30-35% of trials |

Diffraction-quality crystals | 40-50% of crystal hits |

Structure solved | ~85% of diffraction-quality |

Combined: From purified protein to structure, approximately 15% succeed. That means 85% of proteins that reach crystallization trials never yield a structure.

SGC Experience

The Structural Genomics Consortium achieved:

Successful purification of 48% of human proteins attempted

Structures of ~40% of purified proteins solved

More than 300 additional protein domains purified but never crystallized

The lesson: Even expert labs with optimized pipelines have high failure rates. Some proteins simply don't cooperate.

Crystallization Statistics

Analysis of crystallization trials shows:

Only 0.2% of individual crystallization conditions yield crystals

For every 100 purified proteins, ~30 form crystals

Of those, only 13-15 yield structures

The Decision Framework

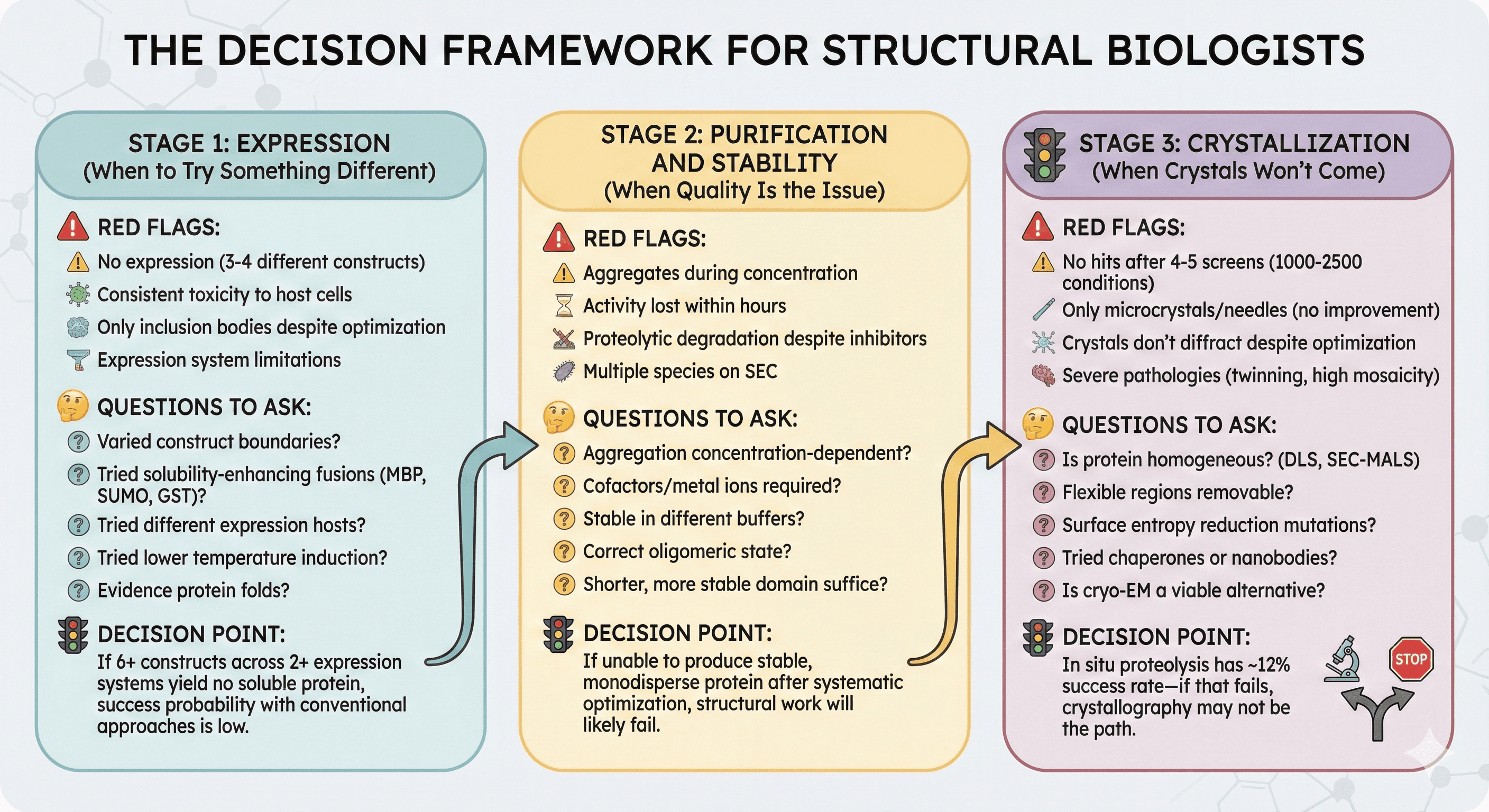

Stage 1: Expression (When to Try Something Different)

Red flags that suggest moving on:

No expression after 3-4 different constructs (different boundaries, tags, fusion partners)

Consistent toxicity to host cells

Only inclusion bodies despite optimization

Expression system limitations that can't be overcome

Questions to ask:

Have you varied construct boundaries systematically?

Have you tried solubility-enhancing fusions (MBP, SUMO, GST)?

Have you tried different expression hosts (E. coli strains, insect, mammalian)?

Have you tried lower temperature induction?

Is there evidence that the protein folds at all in your system?

Decision point: If you've tried 6+ constructs across 2+ expression systems with no soluble protein, the probability of success with conventional approaches is low.

Stage 2: Purification and Stability (When Quality Is the Issue)

Red flags:

Protein aggregates during concentration

Activity lost within hours of purification

Proteolytic degradation despite inhibitors

Multiple species on SEC despite fresh prep

Questions to ask:

Is aggregation concentration-dependent? (Try keeping it dilute)

Are cofactors or metal ions required? (Have you tried reconstitution?)

Is the protein stable in different buffers? (Screen systematically)

Is the oligomeric state correct?

Is there a shorter, more stable domain that would suffice?

Decision point: If you can't produce stable, monodisperse protein after systematic buffer screening and domain optimization, structural work will likely fail anyway.

Stage 3: Crystallization (When Crystals Won't Come)

Red flags:

No hits after screening 4-5 commercial screens (1000-2500 conditions)

Only microcrystals or needles that don't improve

Crystals that don't diffract despite optimization

Crystals with severe pathologies (twinning, high mosaicity)

Questions to ask:

Is the protein homogeneous? (Check by DLS, SEC-MALS)

Are there flexible regions that could be removed?

Would surface entropy reduction mutations help?

Have you tried crystallization chaperones or nanobodies?

Is cryo-EM a viable alternative?

Decision point: In situ proteolysis has ~12% success rate for recalcitrant proteins—if even that fails, crystallography may not be the path.

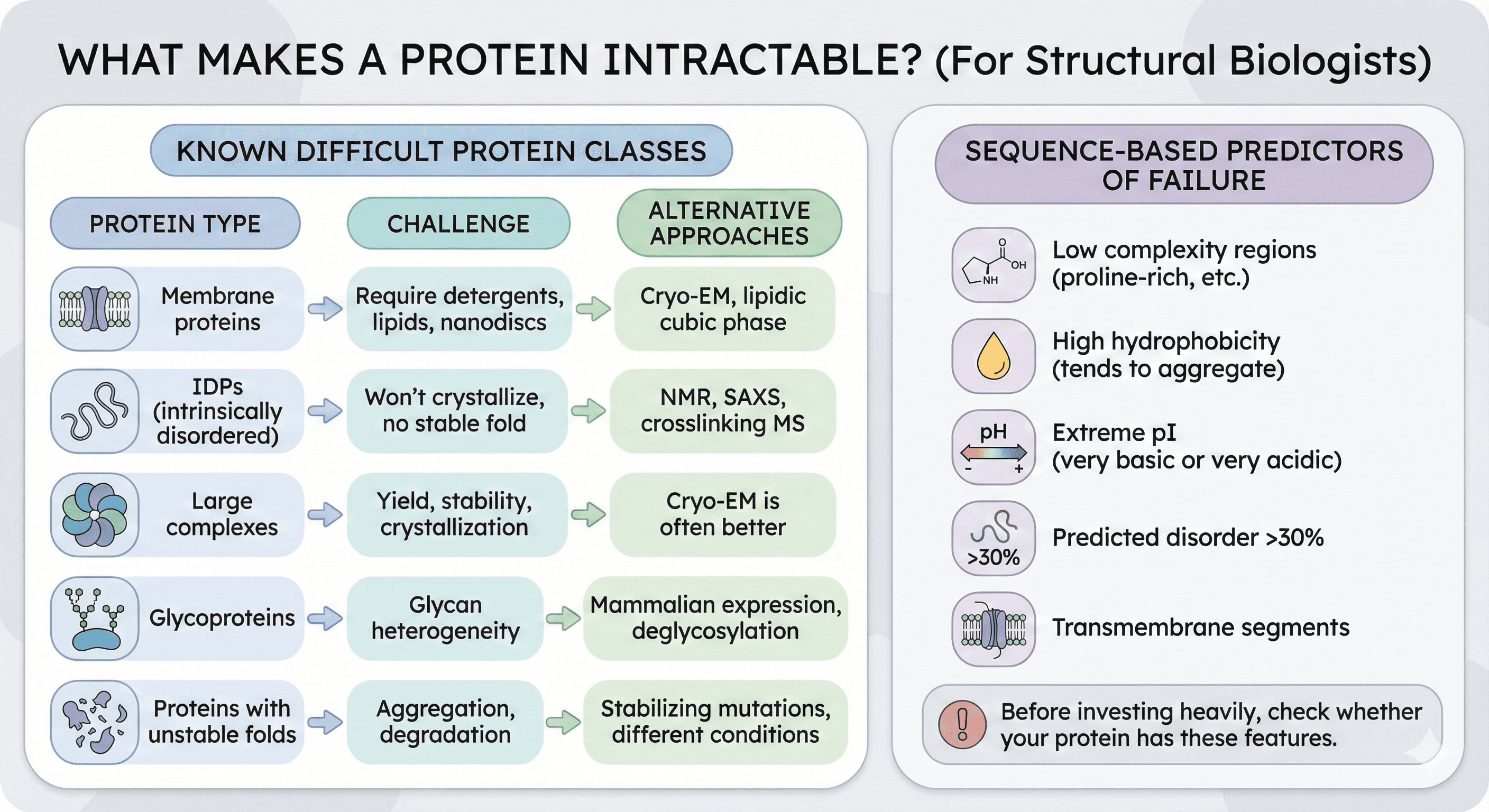

What Makes a Protein Intractable?

Known Difficult Protein Classes

Some protein types have fundamentally lower success rates:

Protein Type | Challenge | Alternative Approaches |

|---|---|---|

Membrane proteins | Require detergents, lipids, nanodiscs | Cryo-EM, lipidic cubic phase |

IDPs (intrinsically disordered) | Won't crystallize, no stable fold | NMR, SAXS, crosslinking MS |

Large complexes | Yield, stability, crystallization | Cryo-EM is often better |

Glycoproteins | Glycan heterogeneity | Mammalian expression, deglycosylation |

Proteins with unstable folds | Aggregation, degradation | Stabilizing mutations, different conditions |

Sequence-Based Predictors of Failure

Studies have identified features that correlate with failure:

Low complexity regions (proline-rich, etc.)

High hydrophobicity (tends to aggregate)

Extreme pI (very basic or very acidic)

Predicted disorder >30%

Transmembrane segments

Before investing heavily, check whether your protein has these features.

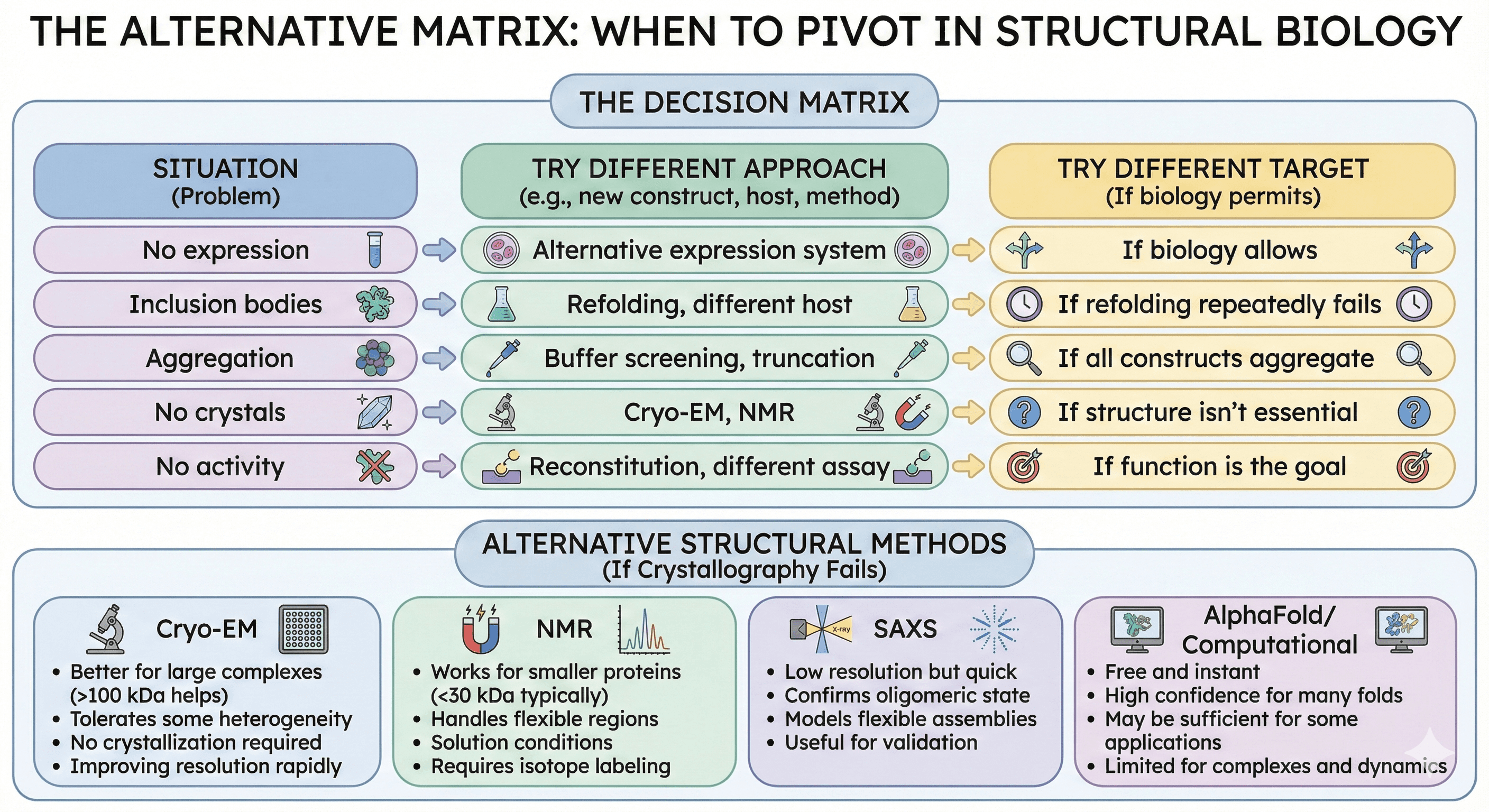

The Alternative Matrix

When to Try a Different Approach vs. a Different Target

Situation | Try Different Approach | Try Different Target |

|---|---|---|

No expression | Alternative expression system | If biology allows |

Inclusion bodies | Refolding, different host | If refolding repeatedly fails |

Aggregation | Buffer screening, truncation | If all constructs aggregate |

No crystals | Cryo-EM, NMR | If structure isn't essential |

No activity | Reconstitution, different assay | If function is the goal |

Alternative Structural Methods

If crystallography fails:

Cryo-EM:

Better for large complexes (>100 kDa helps)

Tolerates some heterogeneity

No crystallization required

Improving resolution rapidly

NMR:

Works for smaller proteins (<30 kDa typically)

Handles flexible regions

Solution conditions

Requires isotope labeling

SAXS:

Low resolution but quick

Confirms oligomeric state

Models flexible assemblies

Useful for validation

AlphaFold/Computational:

Free and instant

High confidence for many folds

May be sufficient for some applications

Limited for complexes and dynamics

Defining "Good Enough"

What Do You Actually Need?

Before deciding to continue or quit, clarify the goal:

Goal | What You Need | When to Quit Pursuing |

|---|---|---|

High-resolution structure | Diffracting crystals or cryo-EM sample | After exhaustive crystallization + no cryo-EM path |

Binding site identification | Structure OR computational prediction + validation | When AlphaFold + mutagenesis suffices |

Functional assay | Active protein | When activity cannot be reconstituted |

Drug screening | Stable, active protein at scale | When production isn't economical |

Target validation | Any evidence of drugability | When multiple orthogonal approaches fail |

Often, you don't need what you think you need. A 2.5 Å structure is great, but a confident AlphaFold model + SPR binding data might answer your actual question.

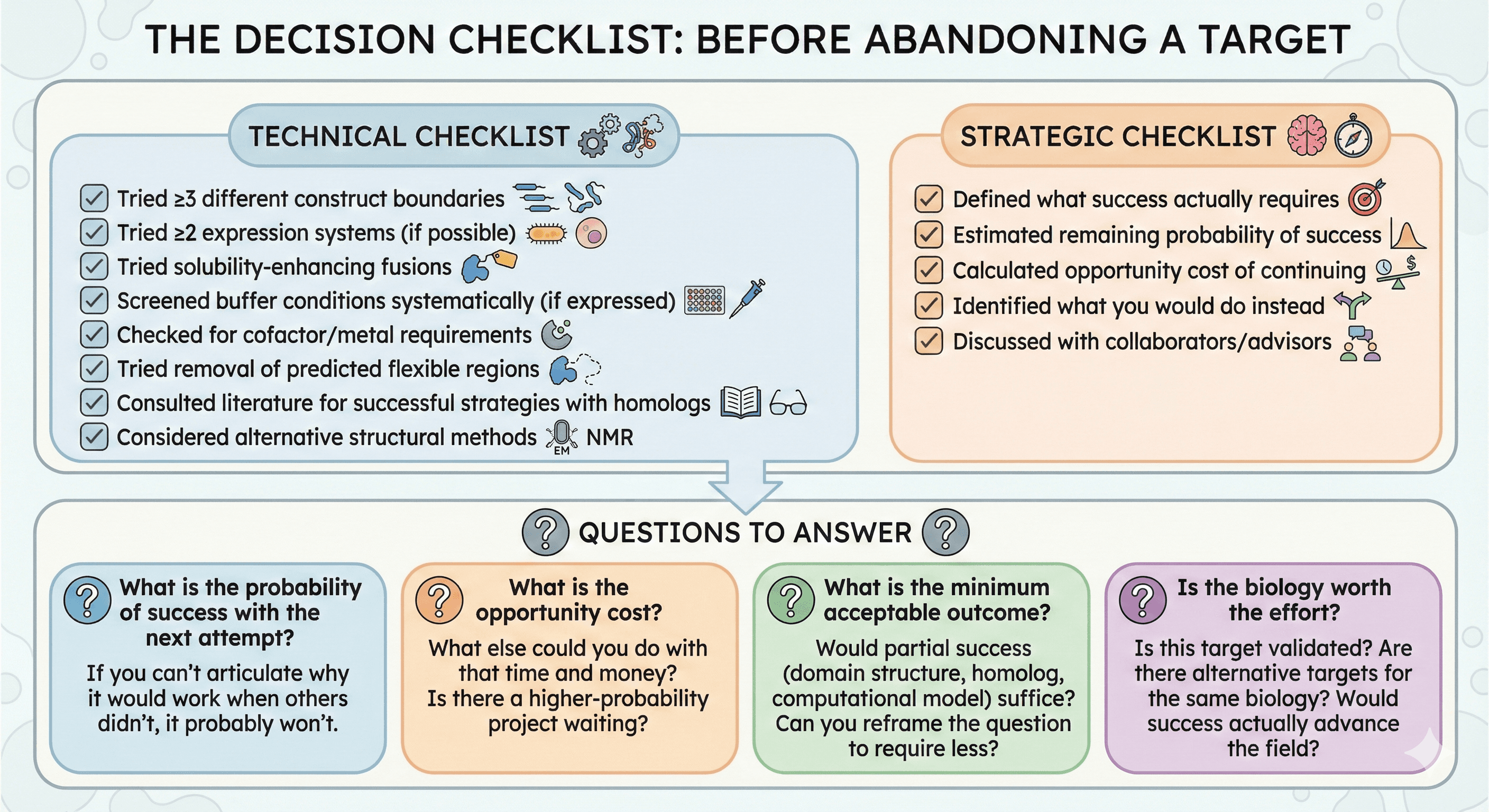

The Decision Checklist

Before Abandoning a Target

Technical checklist:

[ ] Tried ≥3 different construct boundaries

[ ] Tried ≥2 expression systems (if possible)

[ ] Tried solubility-enhancing fusions

[ ] Screened buffer conditions systematically (if expressed)

[ ] Checked for cofactor/metal requirements

[ ] Tried removal of predicted flexible regions

[ ] Consulted literature for successful strategies with homologs

[ ] Considered alternative structural methods

Strategic checklist:

[ ] Defined what success actually requires

[ ] Estimated remaining probability of success

[ ] Calculated opportunity cost of continuing

[ ] Identified what you would do instead

[ ] Discussed with collaborators/advisors

Questions to Answer

What is the probability of success with the next attempt?

If you can't articulate why it would work when others didn't, it probably won't.

What is the opportunity cost?

What else could you do with that time and money?

Is there a higher-probability project waiting?

What is the minimum acceptable outcome?

Would partial success (domain structure, homolog, computational model) suffice?

Can you reframe the question to require less?

Is the biology worth the effort?

Is this target validated?

Are there alternative targets for the same biology?

Would success actually advance the field?

Case Studies

Case 1: The Wise Pivot

Target: Kinase implicated in cancer Investment: 8 months, 15 constructs, E. coli and insect cells Best result: 50 µg aggregated protein Decision: Pivot to AlphaFold model + mutagenesis

Outcome: Computational model identified binding site. Mutagenesis confirmed key residues. Published without structure. Drug discovery proceeded using model.

Lesson: The structure would have been nice, but wasn't actually required for the biological question.

Case 2: The Costly Persistence

Target: "Important" transcription factor Investment: 2 years, 30+ constructs, 3 expression systems, collaboration with expert lab Best result: Low-quality crystals that never improved Decision: Continued because "so much invested"

Outcome: Eventually abandoned after additional year. No publication. No structure. Graduate student delayed.

Lesson: Sunk cost reasoning extended a failing project by a year.

Case 3: The Method Switch

Target: Membrane protein complex Investment: 1 year in crystallography, no crystals Decision: Switch to cryo-EM

Outcome: 3.2 Å cryo-EM structure in 6 months. High-impact publication.

Lesson: The right method for the problem beats persistence with the wrong method.

Case 4: The Rational Abandonment

Target: Protein predicted to be 60% disordered Investment: 6 constructs, 3 months Best result: Soluble but aggregating protein Decision: Abandon—protein is intrinsically unsuitable for structural work

Outcome: Pivoted to NMR studies of the ordered domain. Functional studies using full-length. No single structure, but biological questions answered.

Lesson: Some proteins aren't meant to be crystallized. Recognizing this early saves time.

The Conversation with Your PI/Advisor

How to Propose Abandonment

Don't say: "It's not working and I want to give up."

Do say: "I've systematically tried X, Y, and Z approaches over N months. Based on the data, I estimate the probability of success with continued effort is approximately P%. I propose we either pivot to [alternative approach] or redirect resources to [different project], where the expected value is higher."

Bring data:

What you've tried (constructs, conditions, results)

What the literature says about similar proteins

What alternative approaches exist

What you would do instead

What If They Disagree?

Propose a time-boxed final attempt: "Let me try one more approach for 4 weeks. If it doesn't work, we revisit."

Suggest parallel paths: "Can I start the alternative project while finishing this one?"

Ask what success would look like: "What outcome in the next month would justify continuing?"

The goal is a rational discussion about resource allocation, not a battle of wills.

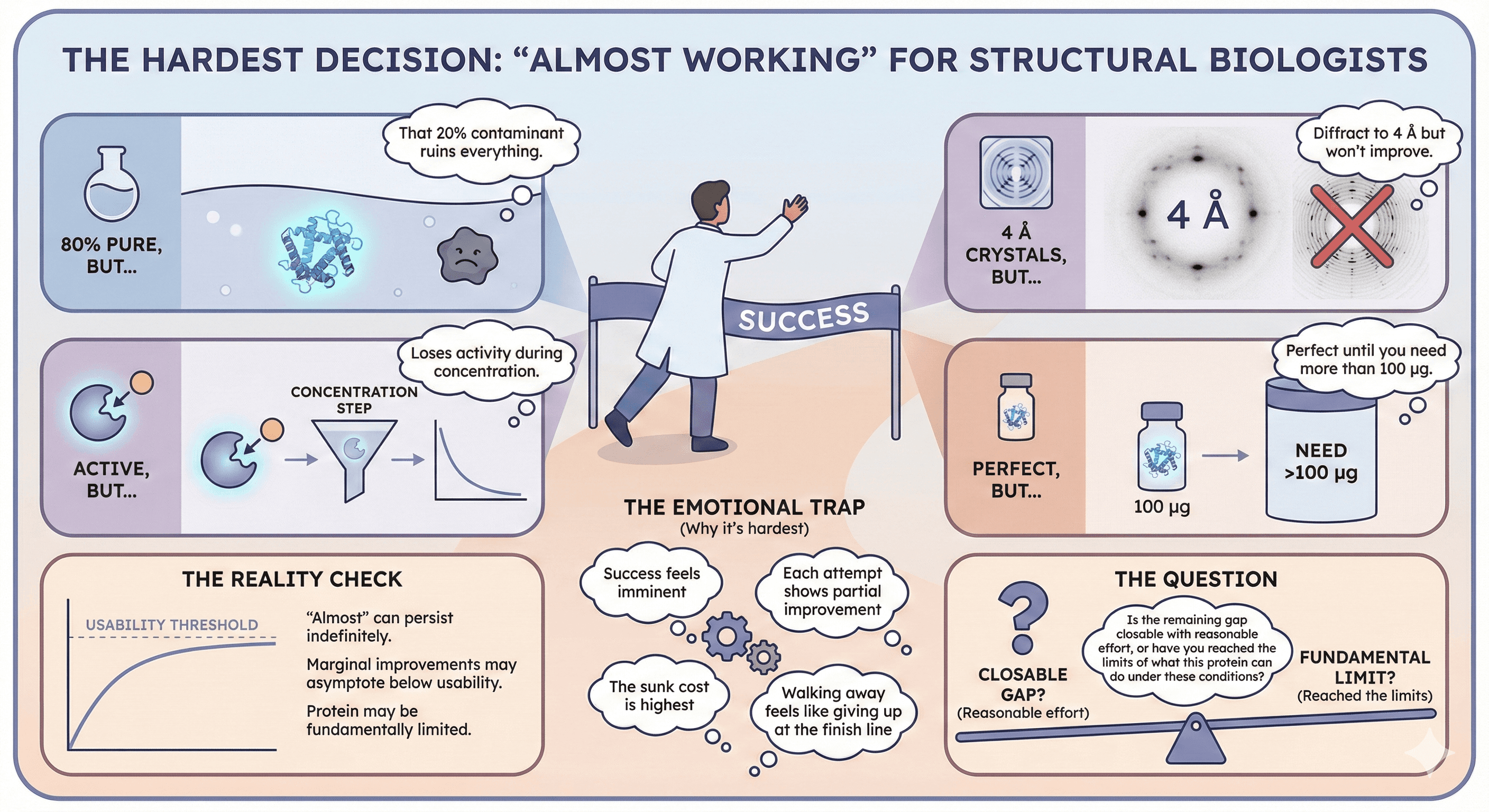

The Hardest Decision: "Almost Working"

When You're Close But Not There

The cruelest scenario: you have protein that almost works.

80% pure, but that 20% contaminant ruins everything

Crystals that diffract to 4 Å but won't improve

Active enzyme that loses activity during concentration

Protein that's perfect until you need more than 100 µg

These situations are the hardest because:

Success feels imminent

Each attempt shows partial improvement

The sunk cost is highest

Walking away feels like giving up at the finish line

The reality check:

"Almost" can persist indefinitely

Marginal improvements may asymptote below usability

The protein may be fundamentally limited

The question: Is the remaining gap closable with reasonable effort, or have you reached the limits of what this protein can do under these conditions?

The Bottom Line

Knowing when to quit is as important as knowing how to persist. The difference between a productive career and years of frustration often comes down to recognizing intractable problems early and redirecting effort to tractable ones.

Sign to Continue | Sign to Quit |

|---|---|

Clear hypothesis for next attempt | No idea why it might work |

New information from each try | Repeating same failures |

Probability estimate improving | Probability estimate flat or declining |

Unique value if successful | Alternative approaches available |

Reasonable time to success | Indefinite timeline |

The final question: If you were starting fresh today, with full knowledge of what you now know about this protein, would you choose to work on it?

If the answer is no, the sunk cost shouldn't change your mind.

Making the Right Target Choices Upfront

The best way to avoid quitting decisions is to make better starting decisions. For researchers selecting protein targets, platforms like Orbion can help assess tractability before you begin:

Disorder prediction: Identify regions likely to cause aggregation or crystallization failure

Expression suitability assessment: Flag proteins likely to require non-standard expression systems

Topology analysis: Identify membrane proteins and other challenging classes

PTM requirements: Predict modifications that may be essential for function

Binding site analysis: Assess whether structural work is actually necessary for your goals

Understanding your protein's challenges before you start helps you choose targets with higher success probability—or at least enter difficult projects with realistic expectations.

References

Slabinski L, et al. (2007). The challenge of protein structure determination—lessons from structural genomics. Protein Science, 16(11):2472-2482. PMC2211687

Savitsky P, et al. (2010). High-throughput production of human proteins for crystallization: The SGC experience. Journal of Structural Biology, 172(1):3-13. PMC2938586

Dong A, et al. (2007). In situ proteolysis for protein crystallization and structure determination. Nature Methods, 4(12):1019-1021. PMC3366506

McPherson A & Gavira JA. (2014). Introduction to protein crystallization. Acta Crystallographica Section F, 70(1):2-20. PMC4601584

Nettleship JE, et al. (2008). Methods for protein characterization by mass spectrometry, thermal shift (ThermoFluor) assay, and multiangle or static light scattering. Methods in Molecular Biology, 426:299-318.

Singh A, et al. (2015). Protein recovery from inclusion bodies of Escherichia coli using mild solubilization process. Microbial Cell Factories, 14:41. PMC4030991

Deng X, et al. (2023). Recent advances in targeting the "undruggable" proteins: from drug discovery to clinical trials. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 8:335. Nature