Blog

Construct Boundary Design: The 4 Problems Killing Your Protein Expression

Jan 9, 2026

You clone the full-length gene. Express it. Inclusion bodies. You try with tags. Still insoluble. You try insect cells. It expresses, but aggregates during purification. You truncate the C-terminus—guess where. The protein is now soluble but completely inactive.

Six months gone, and you still don't have a working construct.

The problem isn't your expression system or purification protocol. It's your construct boundaries. Defining where a protein starts and ends—what to include, what to truncate—is the single most important decision in structural biology.

Key Takeaways

80-90% of construct failures are due to wrong boundaries

Main problems: Disordered termini (40%), flexible internal loops (20%), wrong domain boundaries (30%), bad tag placement (10%)

Average constructs tested: 5-15 per successful structure (traditional trial-and-error)

Cost of poor boundaries: $50-100K wasted per failed construct (6-12 months)

Modern solution: AI-driven boundary prediction reduces constructs tested from 10+ to 1-3

Success rate improvement: 60-80% first-construct success (vs 15-25% traditional)

What Are Construct Boundaries?

Construct boundaries define which residues you express and purify:

N-terminal boundary: Where does your protein start?

C-terminal boundary: Where does it end?

Internal boundaries: Which loops or domains do you include, truncate, or replace?

Example:

Full-length: Residues 1-450

Your construct: Residues 28-412 (N-terminal truncation of 27 residues, C-terminal truncation of 38 residues)

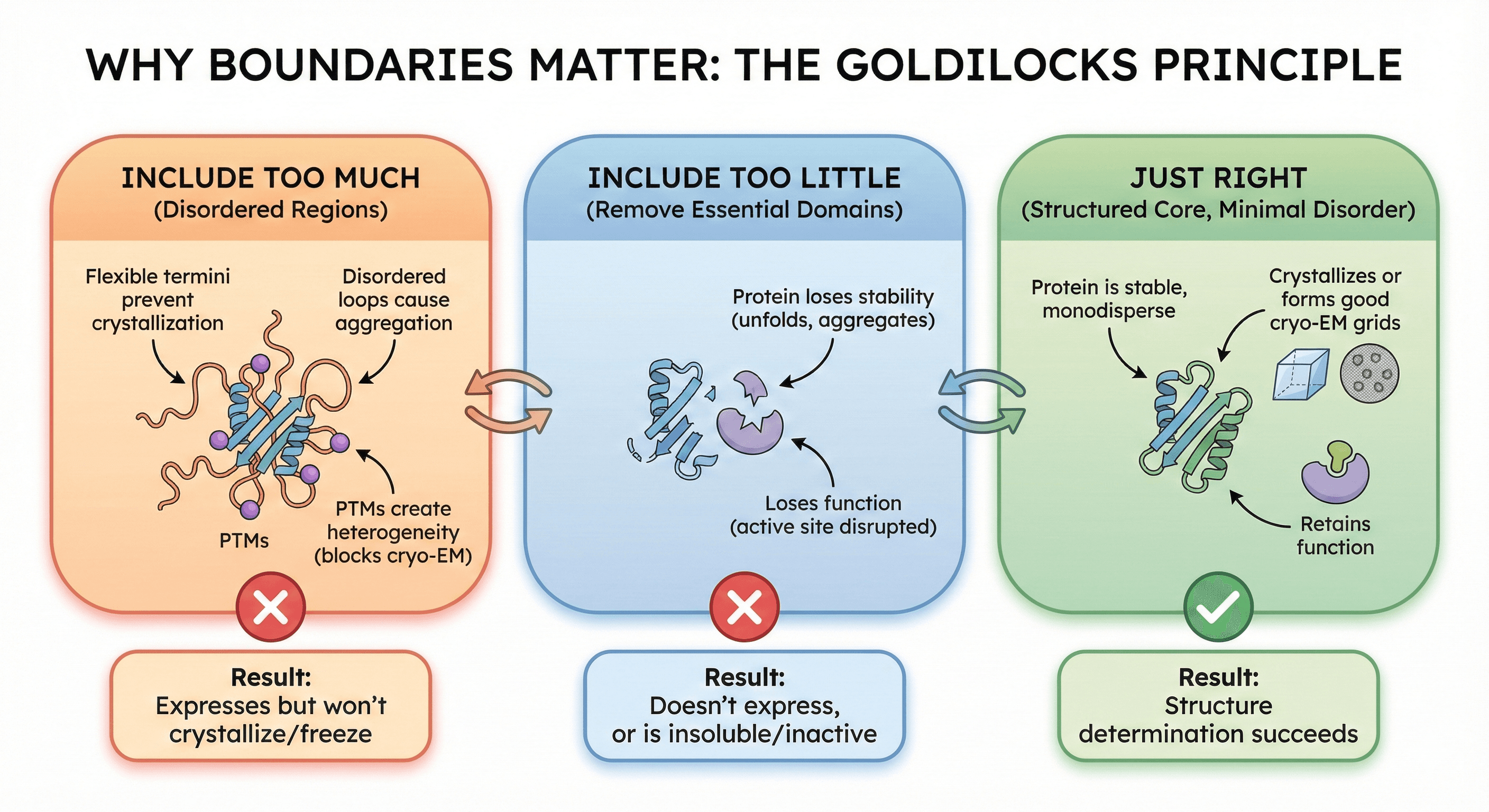

Why Boundaries Matter: The Goldilocks Principle

Include too much (disordered regions):

Flexible termini prevent crystallization

Disordered loops cause aggregation

PTMs create heterogeneity (blocks cryo-EM)

Result: Expresses but won't crystallize/freeze

Include too little (remove essential domains):

Protein loses stability (unfolds, aggregates)

Loses function (active site disrupted)

Result: Doesn't express, or is insoluble/inactive

Just right (structured core, minimal disorder):

Protein is stable, monodisperse

Crystallizes or forms good cryo-EM grids

Retains function

Result: Structure determination succeeds

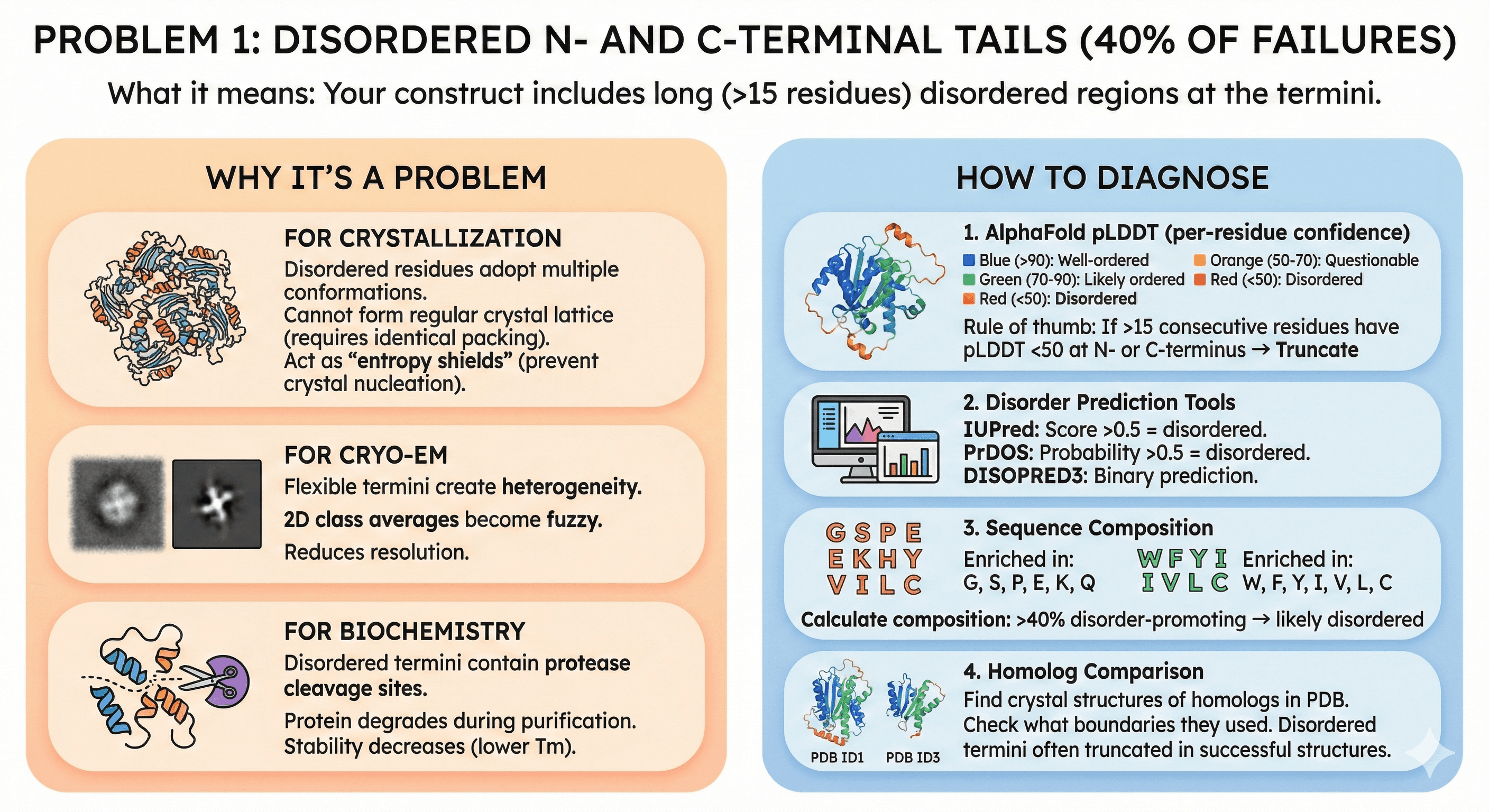

Problem 1: Disordered N- and C-Terminal Tails (40% of Failures)

What it means: Your construct includes long (>15 residues) disordered regions at the termini.

Why It's a Problem

For crystallization:

Disordered residues adopt multiple conformations

Cannot form regular crystal lattice (requires identical packing)

Act as "entropy shields" (prevent crystal nucleation)

For cryo-EM:

Flexible termini create heterogeneity

2D class averages become fuzzy

Reduces resolution

For biochemistry:

Disordered termini contain protease cleavage sites

Protein degrades during purification

Stability decreases (lower Tm)

How to Diagnose

1. AlphaFold pLDDT (per-residue confidence):

Blue (pLDDT >90): Well-ordered

Green (pLDDT 70-90): Likely ordered

Orange (pLDDT 50-70): Questionable

Red (pLDDT <50): Disordered

Rule of thumb: If >15 consecutive residues have pLDDT <50 at N- or C-terminus → Truncate

2. Disorder prediction tools:

IUPred: Score >0.5 = disordered

PrDOS: Probability >0.5 = disordered

DISOPRED3: Binary prediction

3. Sequence composition:

Disordered regions enriched in: Gly, Ser, Pro, Glu, Lys, Gln

Structured regions enriched in: Trp, Phe, Tyr, Ile, Val, Leu, Cys

Calculate composition: >40% disorder-promoting → likely disordered

4. Homolog comparison:

Find crystal structures of homologs in PDB

Check what boundaries they used

Disordered termini often truncated in successful structures

Example: Bacterial Enzyme

Full-length (1-380):

AlphaFold pLDDT:

Residues 1-22: pLDDT 30-50 (disordered)

Residues 23-355: pLDDT 85-95 (structured)

Residues 356-380: pLDDT 40-60 (disordered)

Test constructs:

Construct 1 (1-380, full-length): Expresses, won't crystallize

Construct 2 (23-355, truncate both): Expresses, crystallizes, 2.3 Å

Construct 3 (30-350, aggressive): Expresses, lower yield/stability

Winner: Construct 2 (remove disorder, keep structured core)

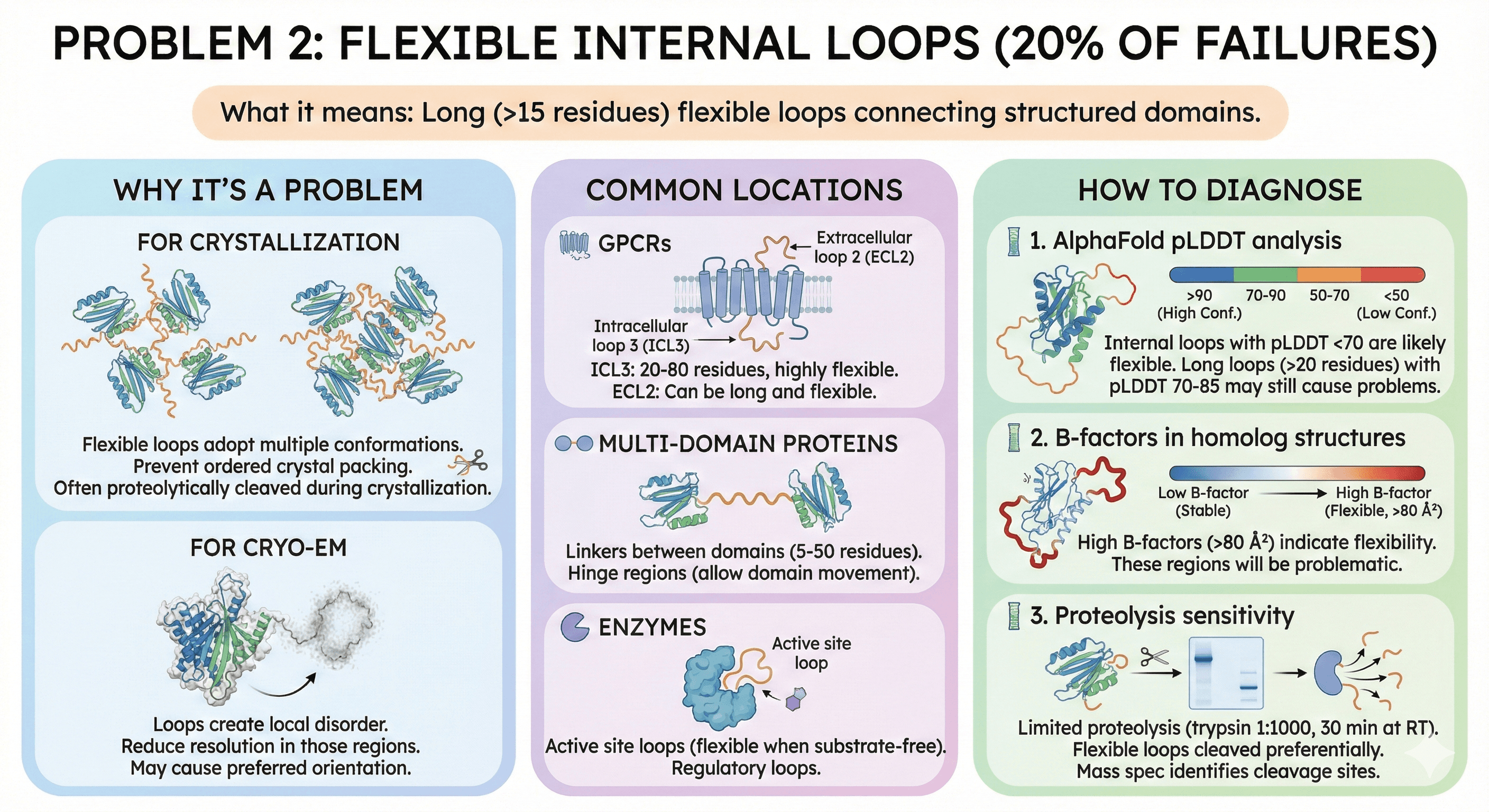

Problem 2: Flexible Internal Loops (20% of Failures)

What it means: Long (>15 residues) flexible loops connecting structured domains.

Why It's a Problem

For crystallization:

Flexible loops adopt multiple conformations

Prevent ordered crystal packing

Often proteolytically cleaved during crystallization

For cryo-EM:

Loops create local disorder

Reduce resolution in those regions

May cause preferred orientation

Common Locations

GPCRs:

Intracellular loop 3 (ICL3): 20-80 residues, highly flexible

Extracellular loop 2 (ECL2): Can be long and flexible

Multi-domain proteins:

Linkers between domains (5-50 residues)

Hinge regions (allow domain movement)

Enzymes:

Active site loops (flexible when substrate-free)

Regulatory loops

How to Diagnose

1. AlphaFold pLDDT analysis:

Internal loops with pLDDT <70 are likely flexible

Long loops (>20 residues) with pLDDT 70-85 may still cause problems

2. B-factors in homolog structures:

High B-factors (>80 Ų) indicate flexibility

These regions will be problematic

3. Proteolysis sensitivity:

Limited proteolysis (trypsin 1:1000, 30 min at RT)

Flexible loops cleaved preferentially

Mass spec identifies cleavage sites

The GPCR ICL3 Problem

Famous example: β2-adrenergic receptor

ICL3 (residues ~230-270): 40 residues, highly flexible

Wild-type: Cannot crystallize

Solution: Replace ICL3 with T4 lysozyme

Construct: Residues 1-229 + T4L + 271-350

Result: First GPCR crystal structure (2007, Nobel Prize 2012)

Why it worked:

T4L is rigid, well-behaved

Provides crystal contacts

Acts as "fiducial marker" for alignment

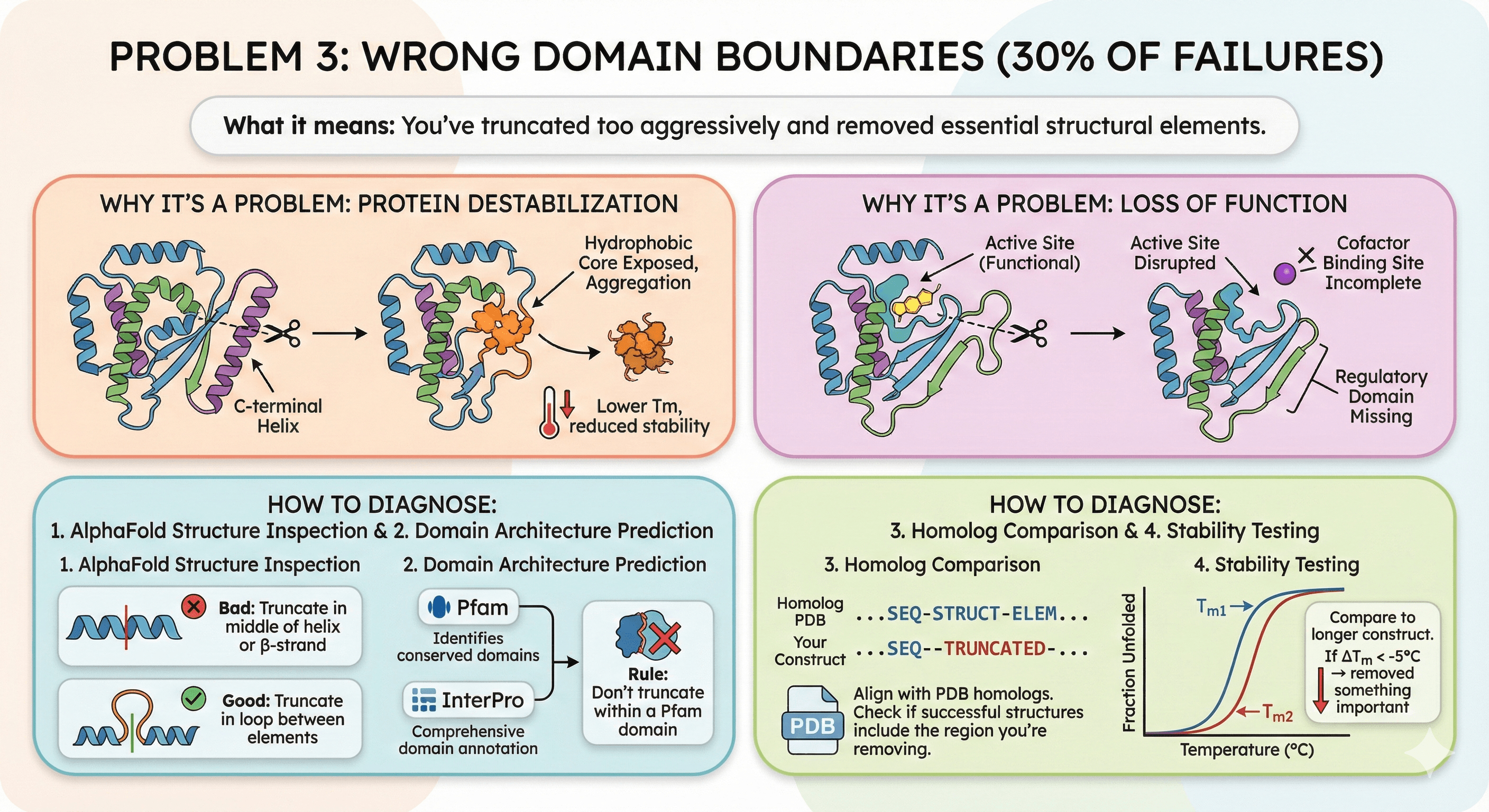

Problem 3: Wrong Domain Boundaries (30% of Failures)

What it means: You've truncated too aggressively and removed essential structural elements.

Why It's a Problem

Protein destabilization:

Removing C-terminal helix exposes hydrophobic core

Protein unfolds, aggregates

Lower Tm, reduced stability

Loss of function:

Active site disrupted

Cofactor binding site incomplete

Regulatory domain missing

How to Diagnose

1. AlphaFold structure inspection:

Check if truncation cuts through secondary structure

Bad: Truncate in middle of helix or β-strand

Good: Truncate in loop between elements

2. Domain architecture prediction:

Pfam: Identifies conserved domains

InterPro: Comprehensive domain annotation

Rule: Don't truncate within a Pfam domain

3. Homolog comparison:

Align with PDB homologs

Check if successful structures include the region you're removing

4. Stability testing:

Express truncated construct, measure Tm

Compare to longer construct

If ΔTm < -5°C → removed something important

Case Study: Removing Essential Helix

Target: Novel bacterial enzyme

Attempt 1:

Construct: Residues 1-320 (removed C-terminal 30 residues)

Expression: Inclusion bodies (completely insoluble)

Analysis:

AlphaFold structure: Residues 310-330 form amphipathic helix

Helix packs against core (stabilizes hydrophobic pocket)

Removing it exposes core → aggregation

Attempt 2:

Construct: Residues 1-340 (keep helix, remove last 10 disordered)

Expression: Soluble, stable

Crystallization: Success, 2.1 Å structure

Lesson: Even one helix can be critical. Respect secondary structure boundaries.

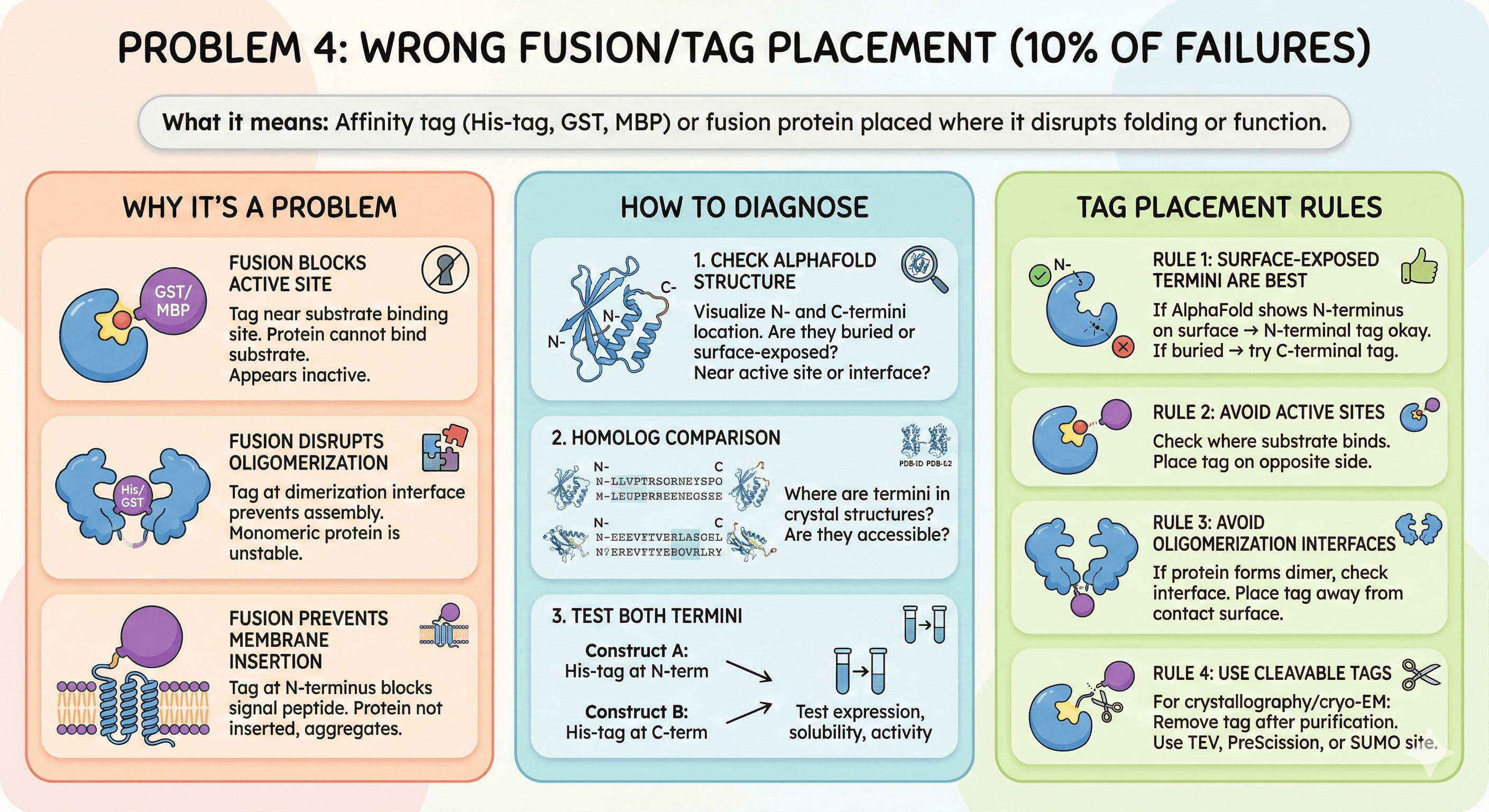

Problem 4: Wrong Fusion/Tag Placement (10% of Failures)

What it means: Affinity tag (His-tag, GST, MBP) or fusion protein placed where it disrupts folding or function.

Why It's a Problem

Fusion blocks active site:

Tag near substrate binding site

Protein cannot bind substrate

Appears inactive

Fusion disrupts oligomerization:

Protein normally forms dimer

Tag at dimerization interface prevents assembly

Monomeric protein is unstable

Fusion prevents membrane insertion:

For membrane proteins, N-terminal signal peptide required

Tag at N-terminus blocks signal peptide

Protein not inserted, aggregates

How to Diagnose

1. Check AlphaFold structure:

Visualize where N- and C-termini are located

Are they buried or surface-exposed?

Are they near active site or oligomerization interface?

2. Homolog comparison:

Where are termini in crystal structures?

Are they accessible?

3. Test both termini:

Construct A: His-tag at N-terminus

Construct B: His-tag at C-terminus

Test expression, solubility, activity

Tag Placement Rules

Rule 1: Surface-exposed termini are best

If AlphaFold shows N-terminus on surface → N-terminal tag okay

If buried → try C-terminal tag

Rule 2: Avoid active sites

Check where substrate binds

Place tag on opposite side

Rule 3: Avoid oligomerization interfaces

If protein forms dimer, check interface

Place tag away from contact surface

Rule 4: Use cleavable tags

For crystallography/cryo-EM: Remove tag after purification

Use TEV protease site, PreScission site, or SUMO

Multi-Domain Proteins: Special Considerations

Example: Full-length (1-520)

Domain 1 (catalytic): Residues 45-280

Linker (flexible): Residues 281-310

Domain 2 (regulatory): Residues 311-490

C-terminal tail (disordered): Residues 491-520

Good construct options:

Construct A: 45-280 (catalytic domain only)

Construct B: 45-490 (both domains, no disordered tail)

Construct C: 311-490 (regulatory domain only)

Bad construct options:

Construct D: 45-250 (truncates within catalytic domain) → Unstable

Construct E: 100-490 (removes part of catalytic domain) → Inactive

Key principle: Keep entire domains, remove linkers between them.

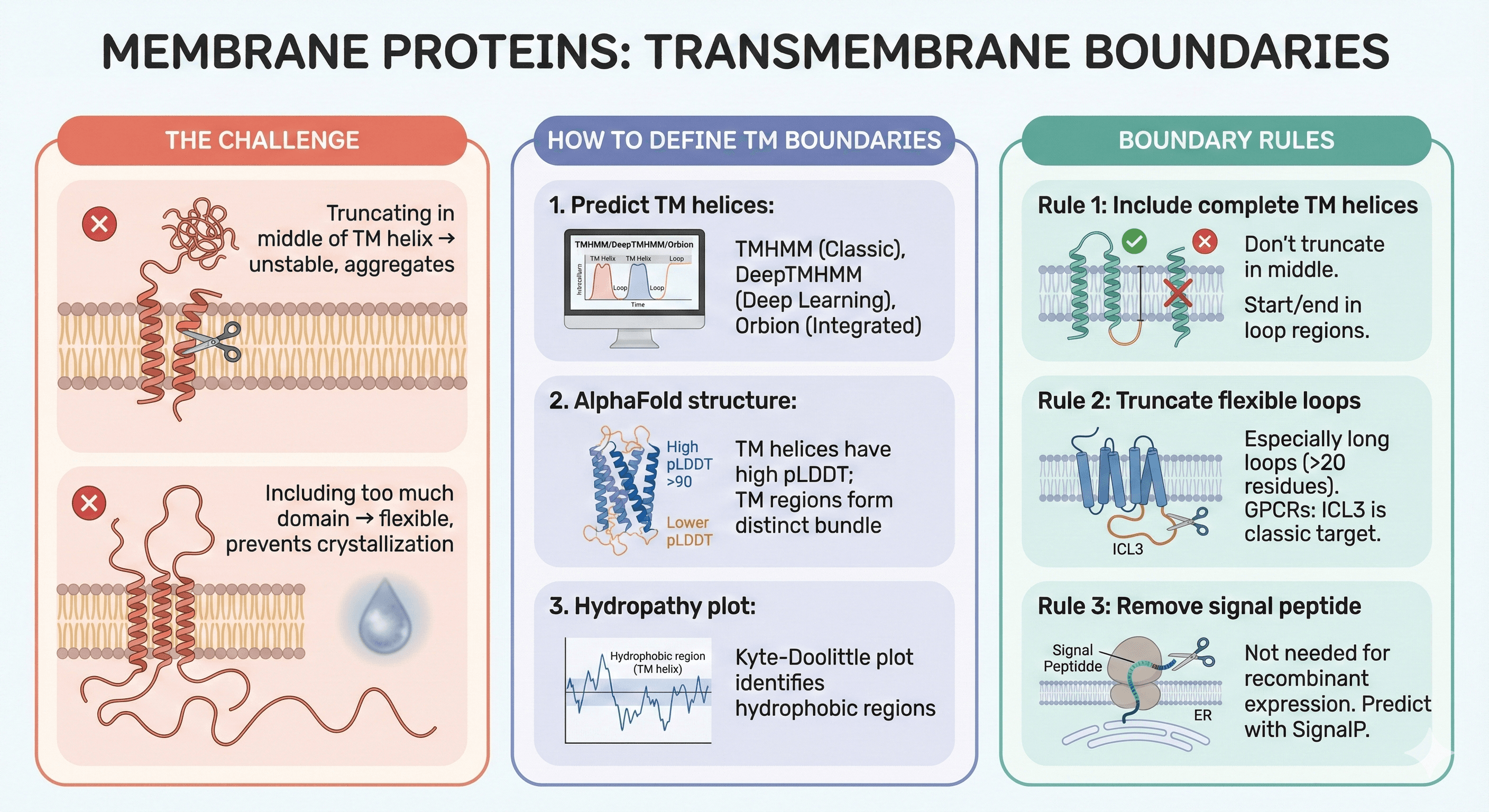

Membrane Proteins: Transmembrane Boundaries

The Challenge

Need to include entire transmembrane (TM) helices

Truncating in middle of TM helix → unstable, aggregates

Including too much intracellular/extracellular domain → flexible, prevents crystallization

How to Define TM Boundaries

1. Predict TM helices:

TMHMM: Classic tool, reliable

DeepTMHMM: Deep learning-based, more accurate

Orbion: Integrates TM prediction with structure

2. AlphaFold structure:

TM helices have high pLDDT (usually >90)

TM regions form distinct bundle

3. Hydropathy plot:

Kyte-Doolittle plot identifies hydrophobic regions (TM helices)

Boundary Rules for Membrane Proteins

Rule 1: Include complete TM helices

Don't truncate in middle of helix

Start/end in loop regions

Rule 2: Truncate flexible loops

Especially long loops (>20 residues)

GPCRs: ICL3 is classic target

Rule 3: Remove signal peptide

Signal peptide directs to ER

Not needed for recombinant expression

Predict with SignalP

Understanding Your Problem: Quick Diagnostic

Symptom | Likely Problem | Quick Test |

|---|---|---|

AlphaFold has long orange/red termini | Disordered termini | Check pLDDT <50 |

Internal orange/red loops (>20 residues) | Flexible loops | Check pLDDT, compare homologs |

Protein insoluble after truncation | Wrong domain boundary | Check if cut through helix/strand |

Protein inactive after expression | Removed essential domain | Check Pfam, homolog structures |

Low expression despite tag | Bad tag placement | Try opposite terminus |

Membrane protein won't insert | Tag blocks signal peptide | Remove N-terminal tag |

Key Takeaway

Construct boundary design isn't guesswork. It's a systematic engineering problem with predictable failure modes:

Disordered termini (40%): Include flexible tails that prevent crystallization

Flexible loops (20%): Internal disorder blocks structure determination

Wrong domain boundaries (30%): Remove essential structural elements

Bad tag placement (10%): Tags disrupt function or folding

Understanding your boundary problem is the first step to fixing it.