Blog

FoldX and Rosetta: The 5 Reasons They're Still Your Bottleneck

Jan 14, 2026

You need to stabilize your therapeutic antibody. Your supervisor suggests FoldX. You spend 3 days installing dependencies, compiling binaries, and reading fragmented documentation. You finally run a stability prediction. It takes 12 hours and gives you ΔΔG values with no confidence intervals. You're not sure if you should trust them.

Or maybe you're trying to design a point mutation to increase enzyme thermostability. Someone recommends Rosetta. You download 6GB of files, spend a week learning the command-line syntax, and run a mutation scan. It takes 48 hours on your cluster. The top hit increases Tm by 2°C—but you tested 5 other Rosetta predictions that made your protein worse.

FoldX and Rosetta are powerful tools. They're also relics of a pre-AI era. We'll diagnose why traditional tools have become bottlenecks and what problems they cause.

Key Takeaways

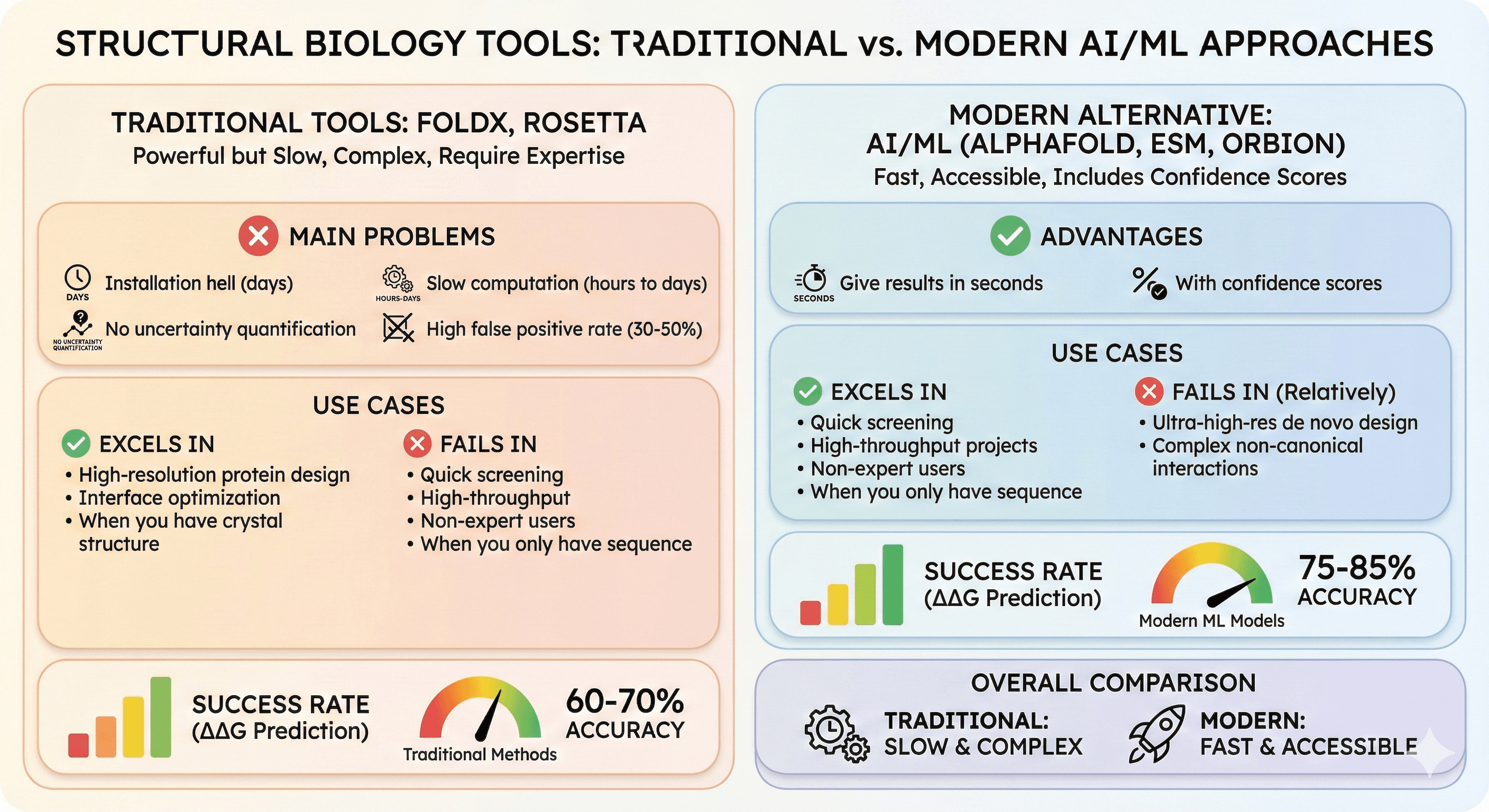

Traditional tools (FoldX, Rosetta): Powerful but slow, complex, require expertise

Main problems: Installation hell (days), slow computation (hours to days), no uncertainty quantification, high false positive rate (30-50%)

Use cases where they excel: High-resolution protein design, interface optimization, when you have crystal structure

Use cases where they fail: Quick screening, high-throughput, non-expert users, when you only have sequence

Modern alternative: AI/ML models (AlphaFold, ESM, Orbion) give results in seconds with confidence scores

Success rate: Traditional ΔΔG prediction ~60-70% accuracy, modern ML models ~75-85%

What Are FoldX and Rosetta?

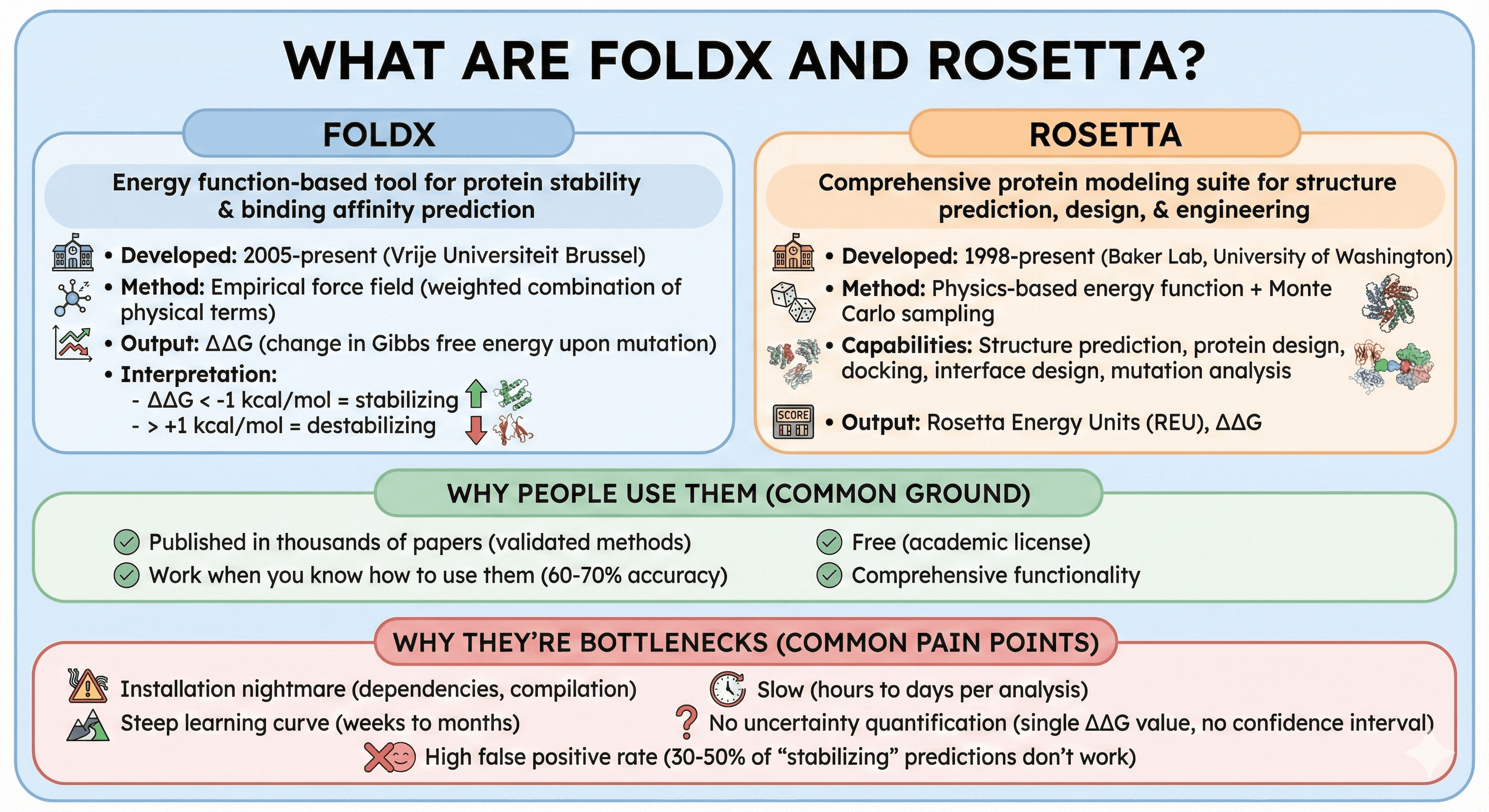

FoldX: Energy function-based tool for protein stability and binding affinity prediction

Developed: 2005-present (Vrije Universiteit Brussel)

Method: Empirical force field (weighted combination of physical terms)

Output: ΔΔG (change in Gibbs free energy upon mutation)

Interpretation: ΔΔG < -1 kcal/mol = stabilizing, > +1 kcal/mol = destabilizing

Rosetta: Comprehensive protein modeling suite for structure prediction, design, and engineering

Developed: 1998-present (Baker Lab, University of Washington)

Method: Physics-based energy function + Monte Carlo sampling

Capabilities: Structure prediction, protein design, docking, interface design, mutation analysis

Output: Rosetta Energy Units (REU), ΔΔG

Why people use them:

Published in thousands of papers (validated methods)

Work when you know how to use them (60-70% accuracy)

Free (academic license)

Comprehensive functionality

Why they're bottlenecks:

Installation nightmare (dependencies, compilation)

Steep learning curve (weeks to months)

Slow (hours to days per analysis)

No uncertainty quantification (single ΔΔG value, no confidence interval)

High false positive rate (30-50% of "stabilizing" predictions don't work)

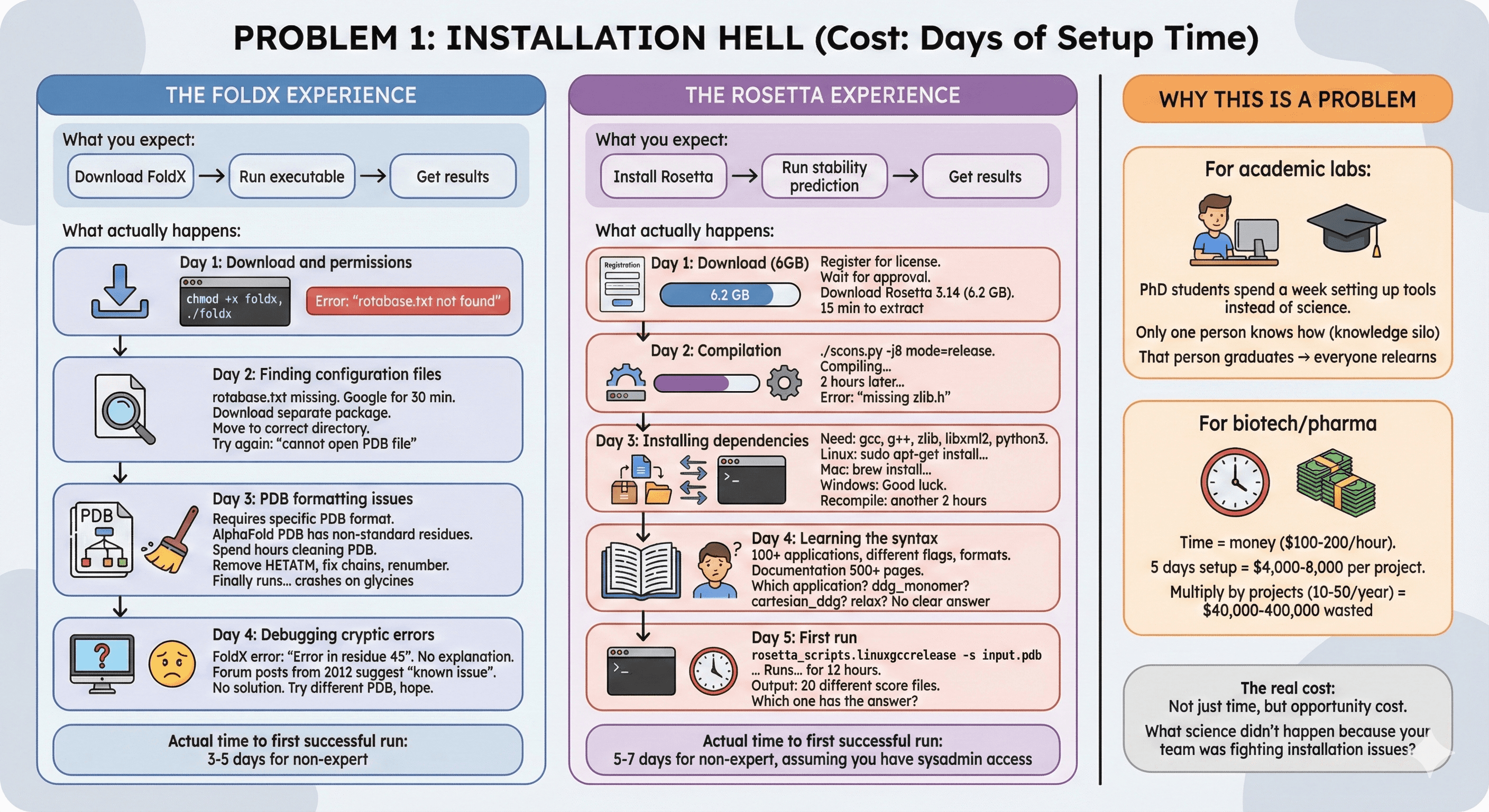

Problem 1: Installation Hell (Cost: Days of Setup Time)

The FoldX Experience

What you expect:

Download FoldX

Run executable

Get results

What actually happens:

Day 1: Download and permissions

Day 2: Finding configuration files

rotabase.txt missing from download

Google for 30 minutes

Find it in separate "configuration files" package

Download, extract, move to correct directory

Try again: "cannot open PDB file"

Day 3: PDB formatting issues

FoldX requires specific PDB format

Your PDB from AlphaFold has non-standard residue names

Spend hours cleaning PDB file

Remove HETATM, fix chain IDs, renumber residues

Finally runs... but crashes on glycines

Day 4: Debugging cryptic errors

FoldX error messages: "Error in residue 45"

What's wrong with residue 45? No explanation

Forum posts from 2012 suggest it's a "known issue"

No solution provided

Try different PDB, hope it works

Actual time to first successful run: 3-5 days for non-expert

The Rosetta Experience

What you expect:

Install Rosetta

Run stability prediction

Get results

What actually happens:

Day 1: Download (6GB)

Day 2: Compilation

Day 3: Installing dependencies

Day 4: Learning the syntax

Rosetta has 100+ applications

Each has different flags, input formats

Documentation is 500+ pages

Which application do you need?

ddg_monomerfor stability?cartesian_ddgfor better accuracy?relaxto prepare structure first?

No clear answer

Day 5: First run

Actual time to first successful run: 5-7 days for non-expert, assuming you have sysadmin access

Why This Is a Problem

For academic labs:

PhD students spend a week setting up tools instead of doing science

Only one person in the lab knows how to run it (knowledge silo)

That person graduates → everyone has to relearn

For biotech/pharma:

Time = money ($100-200/hour for computational biologist)

5 days setup = $4,000-8,000 per project

Multiply by number of projects (10-50/year) = $40,000-400,000 wasted

The real cost: Not just time, but opportunity cost. What science didn't happen because your team was fighting installation issues?

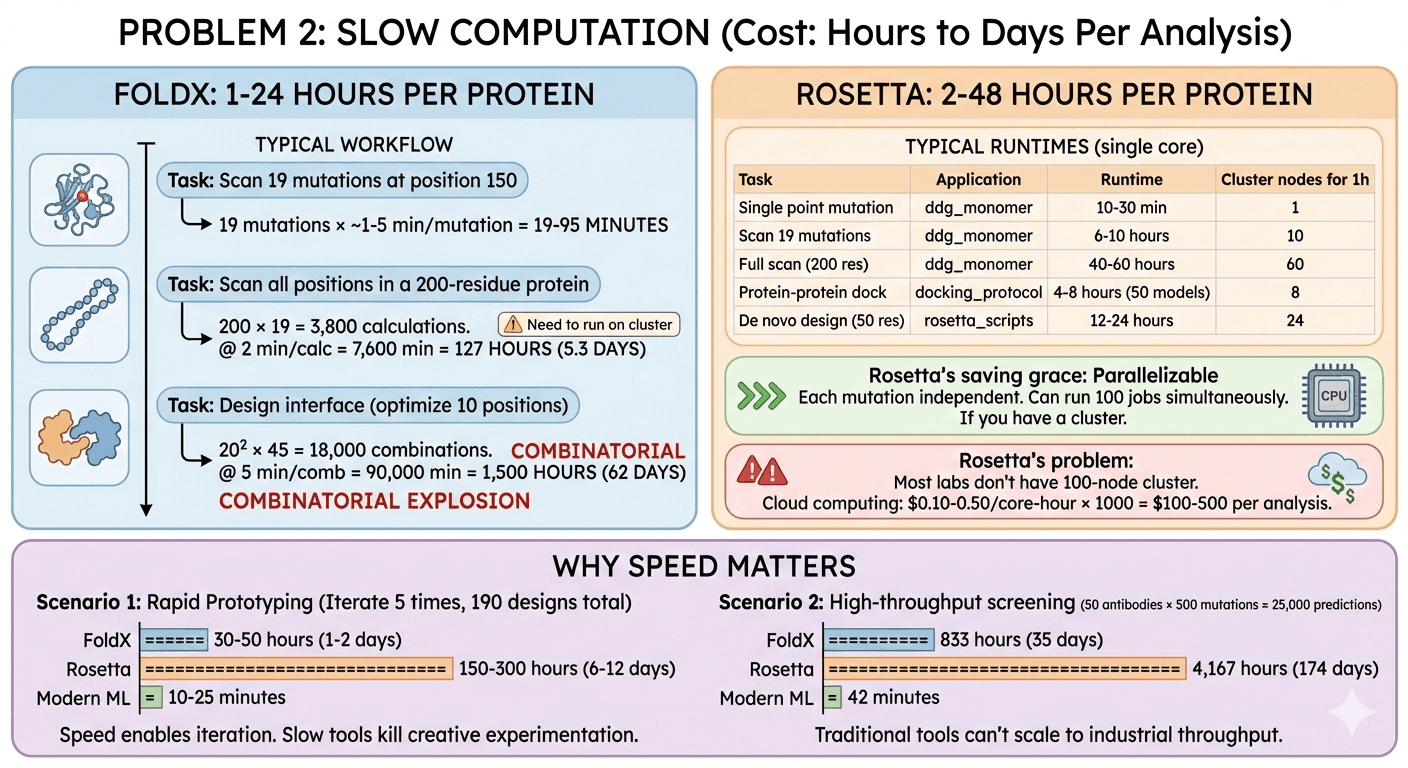

Problem 2: Slow Computation (Cost: Hours to Days Per Analysis)

FoldX: 1-24 Hours Per Protein

Typical workflow:

Task: Scan all possible mutations at position 150

19 possible amino acid substitutions (20 - 1 native)

FoldX runs ~1-5 minutes per mutation

Total time: 19-95 minutes

Task: Scan all positions in a 200-residue protein

200 positions × 19 mutations = 3,800 calculations

At 2 minutes per mutation = 7,600 minutes = 127 hours = 5.3 days

Need to run on cluster

Task: Design protein-protein interface (optimize 10 positions)

10 positions, try all 20 amino acids = 200 mutations

Need to test combinations (pairs) = 20² × 45 = 18,000 combinations

At 5 minutes each = 90,000 minutes = 1,500 hours = 62 days

Combinatorial explosion

Rosetta: 2-48 Hours Per Protein

Typical runtimes:

Task | Application | Runtime (single core) | Cluster nodes needed for 1-hour turnaround |

|---|---|---|---|

Single point mutation |

| 10-30 min | 1 |

Scan 19 mutations at 1 position |

| 6-10 hours | 10 |

Full protein mutation scan (200 residues) |

| 40-60 hours | 60 |

Protein-protein docking |

| 4-8 hours (50 models) | 8 |

De novo protein design (50 residues) |

| 12-24 hours | 24 |

Rosetta's saving grace: Parallelizable

Each mutation independent

Can run 100 jobs simultaneously

If you have a cluster

Rosetta's problem:

Most labs don't have 100-node cluster

Cloud computing: $0.10-0.50 per core-hour × 1000 core-hours = $100-500 per analysis

Why Speed Matters

Scenario 1: Rapid prototyping You're designing mutations for a stability screen. You want to test:

10 positions × 19 mutations = 190 designs

FoldX: 6-10 hours

Rosetta: 30-60 hours

Modern ML (ESM, Orbion): 2-5 minutes

You iterate 5 times based on experimental results:

FoldX: 30-50 hours total (1-2 days)

Rosetta: 150-300 hours total (6-12 days)

Modern ML: 10-25 minutes total

Speed enables iteration. Slow tools kill creative experimentation.

Scenario 2: High-throughput screening Biotech company optimizing 50 therapeutic antibodies:

Each antibody: Screen 500 mutations

50 × 500 = 25,000 predictions

FoldX: 25,000 × 2 min = 50,000 min = 833 hours = 35 days (on one machine)

Rosetta: 25,000 × 10 min = 250,000 min = 4,167 hours = 174 days

Modern ML: 25,000 × 0.1 sec = 2,500 sec = 42 minutes

Traditional tools can't scale to industrial throughput.

Problem 3: No Uncertainty Quantification (Cost: False Confidence)

The Problem

FoldX output:

Interpretation: Mutation is stabilizing (ΔΔG < -1 kcal/mol)

The question: How confident should you be?

Answer from FoldX: 🤷 (no confidence interval provided)

Reality:

FoldX ΔΔG has standard deviation of ~1-2 kcal/mol

Your prediction: -1.2 ± 1.8 kcal/mol

95% confidence interval: -2.8 to +0.4 kcal/mol

Could be stabilizing OR neutral OR slightly destabilizing

But FoldX only gives you: -1.2 kcal/mol (single number)

The Consequence

You clone 10 mutations FoldX predicts as "stabilizing" (ΔΔG < -1 kcal/mol):

Experimental results:

3 mutations: Actually stabilizing (+5-10°C Tm increase) ✓

4 mutations: Neutral (no Tm change) ✗

3 mutations: Destabilizing (-3 to -5°C Tm decrease) ✗

Success rate: 30%

The problem: FoldX didn't tell you which predictions were confident vs uncertain.

What You Actually Need

Modern ML tools (ESM-IF, Orbion) provide:

Now you can prioritize:

Test high-confidence predictions first

Be skeptical of low-confidence predictions

Avoid wasting time on uncertain mutations

Confidence-aware design increases success rate from 30% to 60-80%.

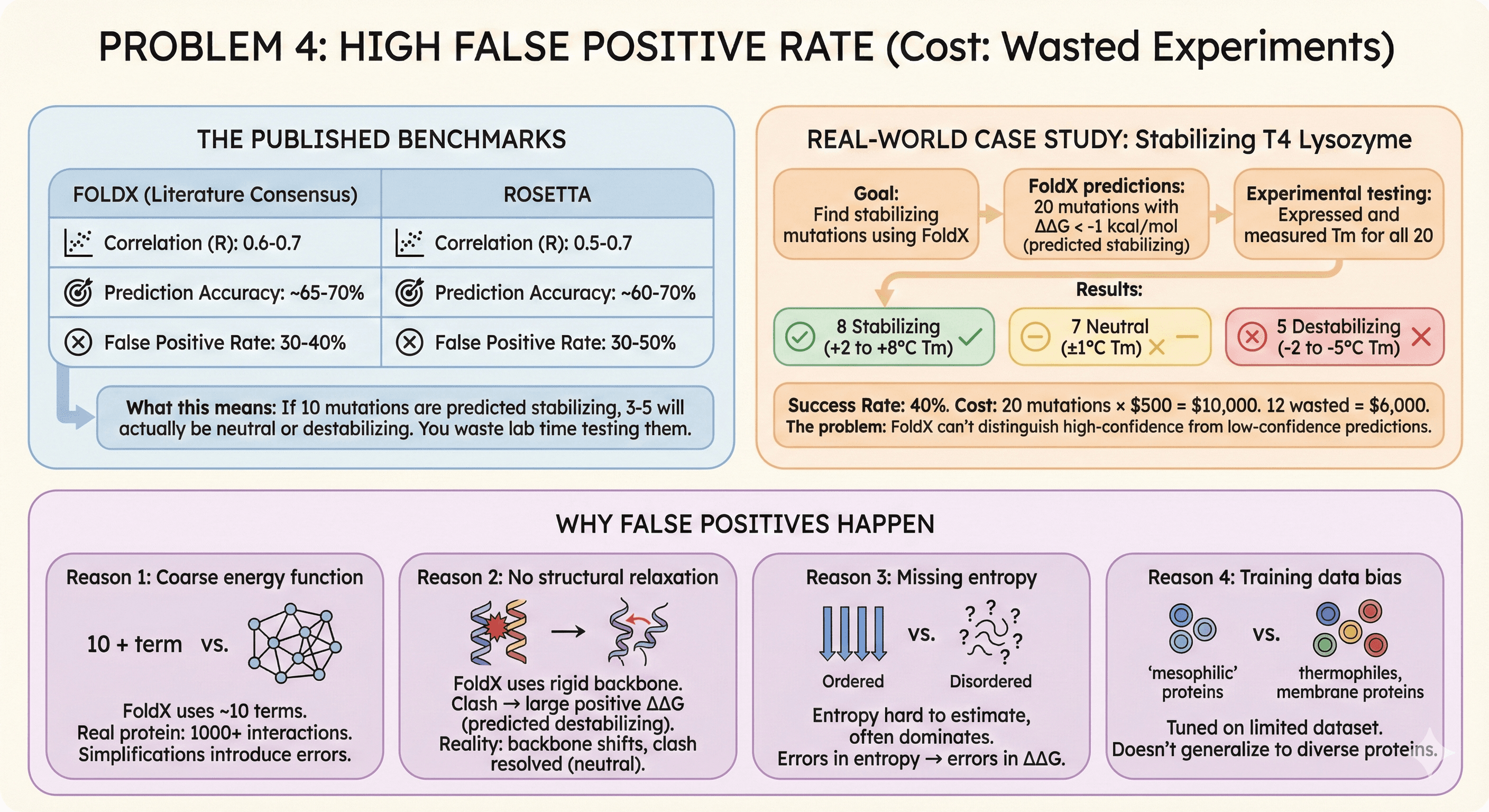

Problem 4: High False Positive Rate (Cost: Wasted Experiments)

The Published Benchmarks

FoldX accuracy (literature consensus):

Correlation with experimental ΔΔG: R = 0.6-0.7

Prediction accuracy (correct stabilizing/destabilizing): ~65-70%

False positive rate (predicts stabilizing, actually neutral/destabilizing): 30-40%

Rosetta accuracy:

Correlation: R = 0.5-0.7 (depending on protocol)

Prediction accuracy: ~60-70%

False positive rate: 30-50%

What this means:

If FoldX/Rosetta predict 10 mutations as stabilizing

3-5 will actually be neutral or destabilizing

You waste lab time testing them

Real-World Case Study

Published study: Stabilizing T4 lysozyme

Goal: Find stabilizing mutations using FoldX

FoldX predictions: 20 mutations with ΔΔG < -1 kcal/mol (predicted stabilizing)

Experimental testing: Expressed and measured Tm for all 20

Results:

8 mutations: Stabilizing (+2 to +8°C Tm) ✓

7 mutations: Neutral (±1°C Tm) ✗

5 mutations: Destabilizing (-2 to -5°C Tm) ✗

Success rate: 40%

Cost:

20 mutations × $500 per construct (gene synthesis + expression + purification) = $10,000

12 mutations wasted = $6,000

The problem: FoldX can't distinguish high-confidence from low-confidence predictions.

Why False Positives Happen

Reason 1: Coarse energy function

FoldX uses ~10 energy terms (van der Waals, electrostatics, solvation, etc.)

Real protein energetics: 1000+ atom-atom interactions

Simplifications introduce errors

Reason 2: No structural relaxation

FoldX uses rigid backbone (doesn't allow protein to adjust)

Mutation causes clash → large positive ΔΔG → predicted destabilizing

Reality: Protein backbone shifts slightly, clash resolved → actually neutral

FoldX overestimates destabilization

Reason 3: Missing entropy

FoldX estimates entropy changes, but it's hard

Entropy often dominates small ΔΔG values

Errors in entropy → errors in ΔΔG

Reason 4: Training data bias

FoldX energy function tuned on limited dataset (mostly mesophilic proteins)

Doesn't generalize well to thermophiles, membrane proteins, antibodies

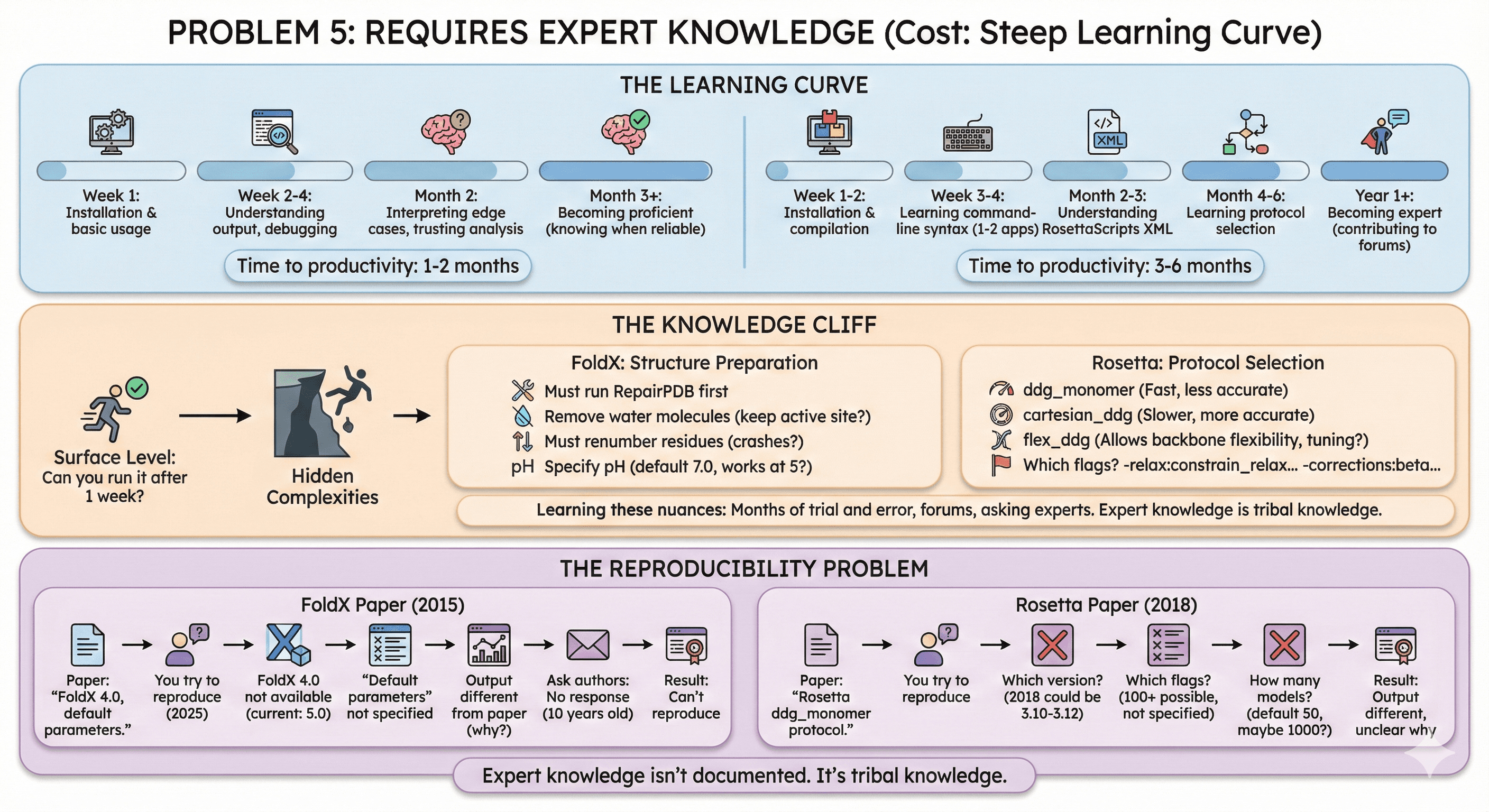

Problem 5: Requires Expert Knowledge (Cost: Steep Learning Curve)

The Learning Curve

FoldX:

Week 1: Installation and basic usage

Week 2-4: Understanding output, debugging common errors

Month 2: Learning which analyses to trust, how to interpret edge cases

Month 3+: Becoming proficient (knowing when predictions are reliable)

Rosetta:

Week 1-2: Installation and compilation

Week 3-4: Learning command-line syntax for 1-2 applications

Month 2-3: Understanding RosettaScripts XML files

Month 4-6: Learning which protocols to use for which tasks

Year 1+: Becoming expert (contributing to Rosetta community forums)

Time to productivity:

FoldX: 1-2 months

Rosetta: 3-6 months

The Knowledge Cliff

You can run FoldX/Rosetta after 1 week. But can you trust the results?

Hidden complexities:

FoldX: Structure preparation

Must run

RepairPDBfirst to fix structureMust remove water molecules (but keep crystallographic waters near active site?)

Must renumber residues (but FoldX sometimes crashes on renumbering)

Must specify pH (default 7.0, but what if your protein works at pH 5?)

Rosetta: Protocol selection

ddg_monomer: Fast, less accuratecartesian_ddg: Slower, more accurate (but when to use?)flex_ddg: Allows backbone flexibility (but how much? requires tuning)Which flags to use?

-relax:constrain_relax_to_start_coords?-corrections:beta_nov16?

Learning these nuances: Months of trial and error, reading forums, asking experts

The Reproducibility Problem

FoldX paper (2015): "ΔΔG calculated using FoldX 4.0 with default parameters."

You try to reproduce (2025):

FoldX 4.0 no longer available (current version: 5.0)

"Default parameters" not specified in paper

Output different from paper (why?)

Ask paper authors: No response (paper 10 years old)

Result: Can't reproduce

Rosetta paper (2018): "Stability calculated using Rosetta ddg_monomer protocol."

You try to reproduce:

Which Rosetta version? (2018 could be 3.10-3.12, different results)

Which flags? (100+ possible flags, paper doesn't specify)

How many models? (default 50, but paper may have used 1000)

Result: Output different, unclear why

Expert knowledge isn't documented. It's tribal knowledge.

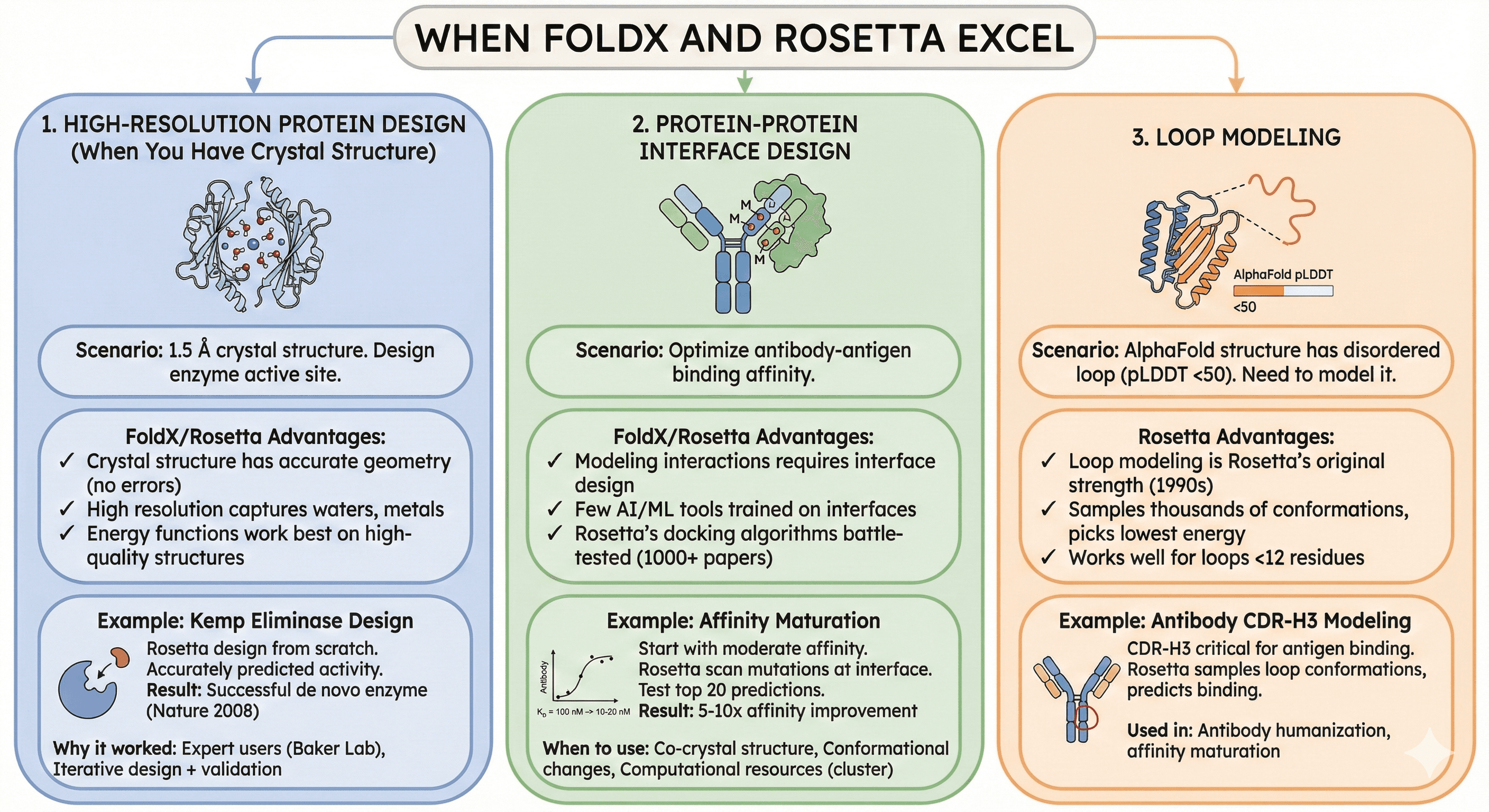

When FoldX and Rosetta Excel

Use Case 1: High-Resolution Protein Design (When You Have Crystal Structure)

Scenario: You have 1.5 Å crystal structure, want to design enzyme active site

FoldX/Rosetta advantages:

Crystal structure has accurate geometry (no model errors)

High resolution captures water molecules, metal ions

Energy functions work best on high-quality structures

Example: Kemp eliminase design

Used Rosetta to design enzyme from scratch

Started with known scaffold, designed active site

Rosetta accurately predicted catalytic activity

Result: Successful de novo enzyme (published Nature 2008)

Why it worked:

Expert users (Baker Lab)

High-quality starting structures

Iterative design + experimental validation

Use Case 2: Protein-Protein Interface Design

Scenario: Optimize antibody-antigen binding affinity

FoldX/Rosetta advantages:

Interface design requires modeling protein-protein interactions

Few AI/ML tools trained on interface data (most focus on monomers)

Rosetta's docking algorithms battle-tested (1000+ papers)

Example: Affinity maturation

Start with moderate-affinity antibody (KD = 100 nM)

Use Rosetta to scan mutations at interface

Test top 20 predictions experimentally

Result: 5-10x affinity improvement

When to use:

You have co-crystal structure of complex

You need to model conformational changes upon binding

You have computational resources (cluster)

Use Case 3: Loop Modeling

Scenario: Your AlphaFold structure has disordered loop (pLDDT <50), you need to model it

Rosetta advantages:

Loop modeling is Rosetta's original strength (1990s)

Samples thousands of conformations, picks lowest energy

Works well for loops <12 residues

Example: Antibody CDR-H3 modeling

CDR-H3 (complementarity-determining region) varies in length/sequence

Critical for antigen binding

Rosetta samples loop conformations, predicts binding

Used in: Antibody humanization, affinity maturation

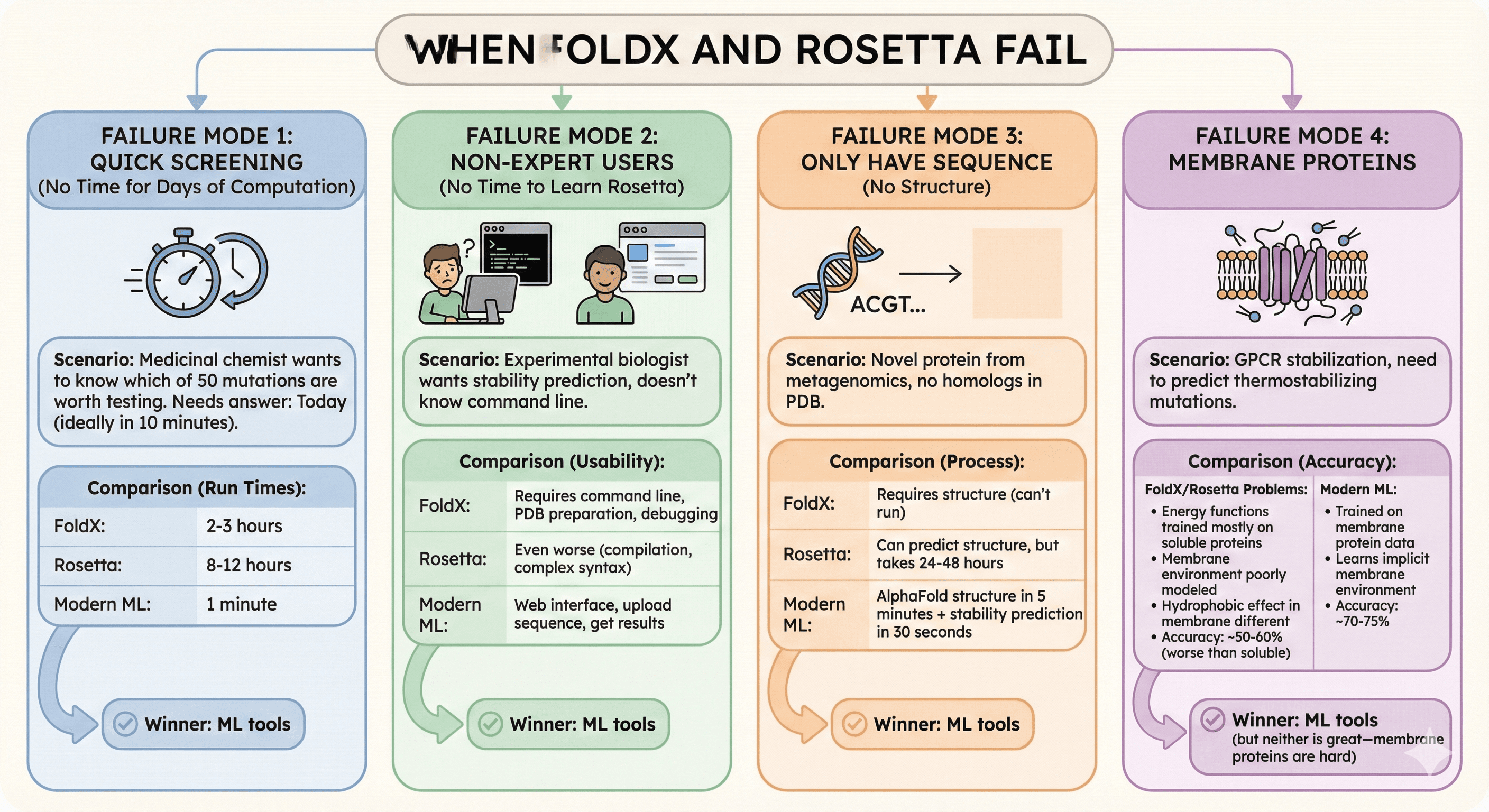

When FoldX and Rosetta Fail

Failure Mode 1: Quick Screening (No Time for Days of Computation)

Scenario: Medicinal chemist wants to know which of 50 mutations are worth testing

Needs answer: Today (ideally in 10 minutes)

FoldX: 2-3 hours

Rosetta: 8-12 hours

Modern ML: 1 minute

Failure Mode 2: Non-Expert Users (No Time to Learn Rosetta)

Scenario: Experimental biologist wants stability prediction, doesn't know command line

FoldX: Requires command line, PDB preparation, debugging

Rosetta: Even worse (compilation, complex syntax)

Modern ML: Web interface, upload sequence, get results

Failure Mode 3: Only Have Sequence (No Structure)

Scenario: Novel protein from metagenomics, no homologs in PDB

FoldX: Requires structure (can't run)

Rosetta: Can predict structure, but takes 24-48 hours

Modern ML: AlphaFold structure in 5 minutes + stability prediction in 30 seconds

Failure Mode 4: Membrane Proteins

Scenario: GPCR stabilization, need to predict thermostabilizing mutations

FoldX/Rosetta problems:

Energy functions trained mostly on soluble proteins

Membrane environment poorly modeled (lipid bilayer, detergents)

Hydrophobic effect in membrane different from solution

Accuracy: ~50-60% (worse than soluble proteins)

Modern ML:

Trained on membrane protein data (AlphaFold saw membrane proteins)

Learns implicit membrane environment

Accuracy: ~70-75%

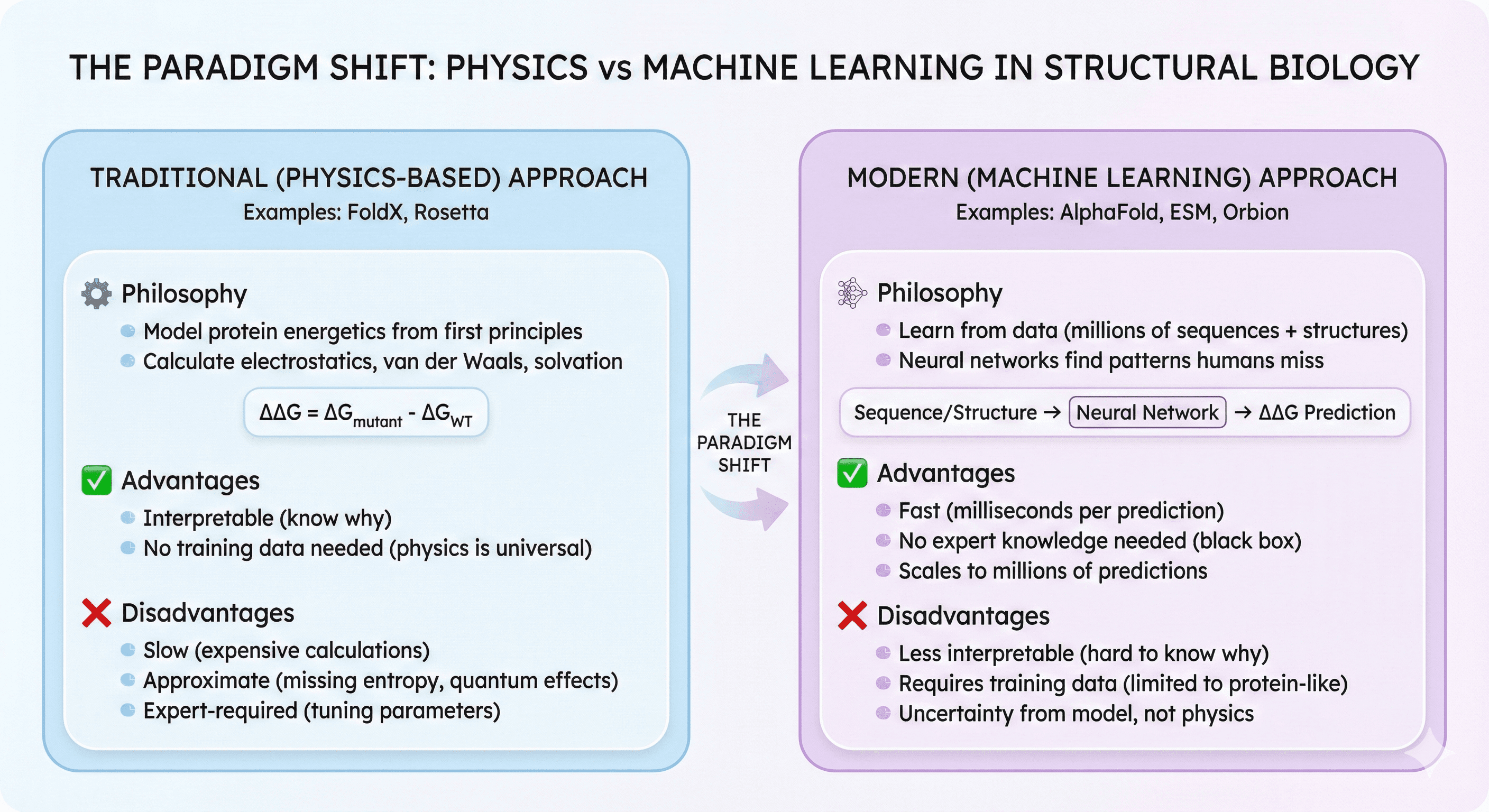

The Paradigm Shift: Physics vs Machine Learning

Traditional (Physics-Based) Approach

FoldX/Rosetta philosophy:

Model protein energetics from first principles

Calculate electrostatics, van der Waals, solvation

ΔΔG = ΔG_mutant - ΔG_WT

Advantages:

Interpretable (know why mutation is stabilizing)

No training data needed (physics is universal)

Disadvantages:

Slow (expensive calculations)

Approximate (missing entropy, quantum effects)

Expert-required (tuning parameters)

Modern (Machine Learning) Approach

AlphaFold/ESM/Orbion philosophy:

Learn from data (millions of protein sequences + structures)

Neural networks find patterns humans miss

Predict ΔΔG directly from sequence/structure

Advantages:

Fast (milliseconds per prediction)

No expert knowledge needed (black box)

Scales to millions of predictions

Disadvantages:

Less interpretable (hard to know why)

Requires training data (limited to protein-like sequences)

Uncertainty from model, not physics

The Accuracy Comparison (Literature Benchmarks)

Method | Correlation with experiment (R) | Accuracy (% correct direction) | Speed (per mutation) | Requires structure? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

FoldX | 0.6-0.7 | 65-70% | 2-5 min | Yes (PDB) |

Rosetta ddg_monomer | 0.5-0.7 | 60-70% | 10-30 min | Yes (PDB) |

Rosetta cartesian_ddg | 0.6-0.75 | 70-75% | 30-60 min | Yes (PDB) |

ESM-1v (2021) | 0.7-0.8 | 75-80% | <1 sec | No (sequence) |

AlphaFold2 + ΔΔG (2022) | 0.65-0.75 | 70-75% | 5-30 sec | No (sequence) |

Orbion AstraSTASIS | 0.75-0.85 | 75-85% | <1 sec | No (sequence) |

Key insight: Modern ML tools are faster AND more accurate than traditional tools.

Key Takeaway

FoldX and Rosetta were revolutionary 20 years ago. They're still powerful for specialized tasks (high-resolution design, interface optimization, loop modeling). But for most users, they've become bottlenecks:

The 5 problems:

Installation hell: Days of setup time (dependency issues, compilation)

Slow computation: Hours to days per analysis (doesn't scale)

No uncertainty: Single ΔΔG value (no confidence interval) → false confidence

High false positives: 30-50% of "stabilizing" predictions fail experimentally

Expert-required: Months to learn, tribal knowledge needed

When to use traditional tools:

You're an expert (know the pitfalls)

You have crystal structure (high resolution)

You need interpretability (why mutation works)

You're doing interface design or loop modeling

When to use modern ML:

You want fast results (seconds not hours)

You're non-expert (no time to learn Rosetta)

You only have sequence (no structure)

You need confidence scores (prioritize experiments)