Blog

Why Your Protein Aggregates (And How to Fix It): A Structural Biologist's Guide

Dec 11, 2025

You expressed your protein. It looked perfect in gel filtration. Then you concentrated it to 5 mg/mL and found a white precipitate at the bottom of the tube. Welcome to the most frustrating problem in protein science: aggregation. It kills more projects than any other technical failure, costs labs hundreds of thousands of dollars in wasted time, and is the reason 30-40% of potential drug targets are labeled "undruggable." Here's why it happens—and how to fix it.

Key Takeaways

60-80% of recombinant proteins show some aggregation during expression or purification

Main culprits: Exposed hydrophobic patches, partial unfolding, concentration-dependent oligomerization

Cost of failure: $50k-100k per failed protein target (6-12 months of wasted effort)

Solution: Computational prediction of aggregation hotspots + rational mutagenesis increases success rates 2-5×

Modern tools: AI-driven prediction (Orbion, AGGRESCAN3D, CamSol) dramatically reduces failure rates

The Aggregation Problem: Why It Matters

By the Numbers

Academic research:

40% of proteins in structural genomics pipelines fail due to aggregation

Average time lost per failed target: 6-12 months

Opportunity cost: Cannot pursue alternative targets

Biopharmaceuticals:

FDA requires <2% aggregation for therapeutic antibody approval

High-concentration formulations (>100 mg/mL for subcutaneous injection) are aggregation-prone

Market impact: A rejected antibody formulation = $500M-1B loss

Industrial enzymes:

Aggregation during fermentation reduces yield 50-90%

Stability loss during storage renders products unusable

Economic impact: $30-50k per failed batch

The pattern: Aggregation isn't a niche problem. It's the primary technical barrier in protein production, structural biology, and therapeutics.

The Three Types of Aggregation

Not all aggregation is the same. Understanding the mechanism helps you choose the right fix.

Type 1: Co-Translational Aggregation (Inclusion Bodies)

When it happens: During protein expression in the cell (usually E. coli)

What you see: Insoluble protein pellet after cell lysis. Protein is in the insoluble fraction on SDS-PAGE.

Mechanism:

Protein folds faster than chaperones can assist

Hydrophobic regions exposed during folding stick together

Misfolded intermediates aggregate irreversibly

Prevalence:

60-70% of membrane proteins in E. coli

30-40% of eukaryotic proteins in E. coli

Less common in eukaryotic expression (yeast, insect, mammalian cells have better chaperone machinery)

Example: GPCRs in E. coli G-protein coupled receptors are 7-transmembrane proteins. When expressed in bacteria:

Lack of mammalian chaperones

No membrane insertion machinery

Hydrophobic transmembrane helices aggregate instantly

Result: 100% insoluble

Solution pathway:

Try lower temperature expression (16°C vs 37°C) - slower folding, more time for chaperones

Co-express chaperones (GroEL/ES, DnaK/J)

Switch to eukaryotic system (Pichia, insect cells, HEK293)

Add solubility tags (MBP, SUMO, GST)

Type 2: Post-Purification Aggregation (Concentration-Induced)

When it happens: During concentration, storage, or freeze-thaw

What you see:

Protein is initially soluble after purification

Concentrating above threshold (e.g., >2 mg/mL) causes precipitation

Cloudy solution, white precipitate, loss of activity

Mechanism:

Protein-protein collisions increase with concentration (C²)

Transient unfolding exposes aggregation-prone regions (APRs)

Oligomers form → grow into larger aggregates → precipitate

Prevalence:

~50% of antibodies show concentration-dependent aggregation

Therapeutic proteins requiring high concentration (>50 mg/mL) almost always face this

Storage-induced: Freeze-thaw cycles cause partial unfolding

Example: Therapeutic Antibody Formulation Monoclonal antibodies for subcutaneous injection need >100 mg/mL:

At 10 mg/mL: Stable for months

At 100 mg/mL: Aggregates form within days

At 150 mg/mL: Immediate precipitation

FDA requirement: <2% high-molecular-weight species (aggregates) at shelf life

Solution pathway:

Identify aggregation hotspots (hydrophobic surface patches)

Introduce surface mutations to reduce patch size (hydrophobic → polar)

Optimize buffer (pH, salt, additives like arginine or sucrose)

Use stabilizing excipients (polysorbate 80, trehalose)

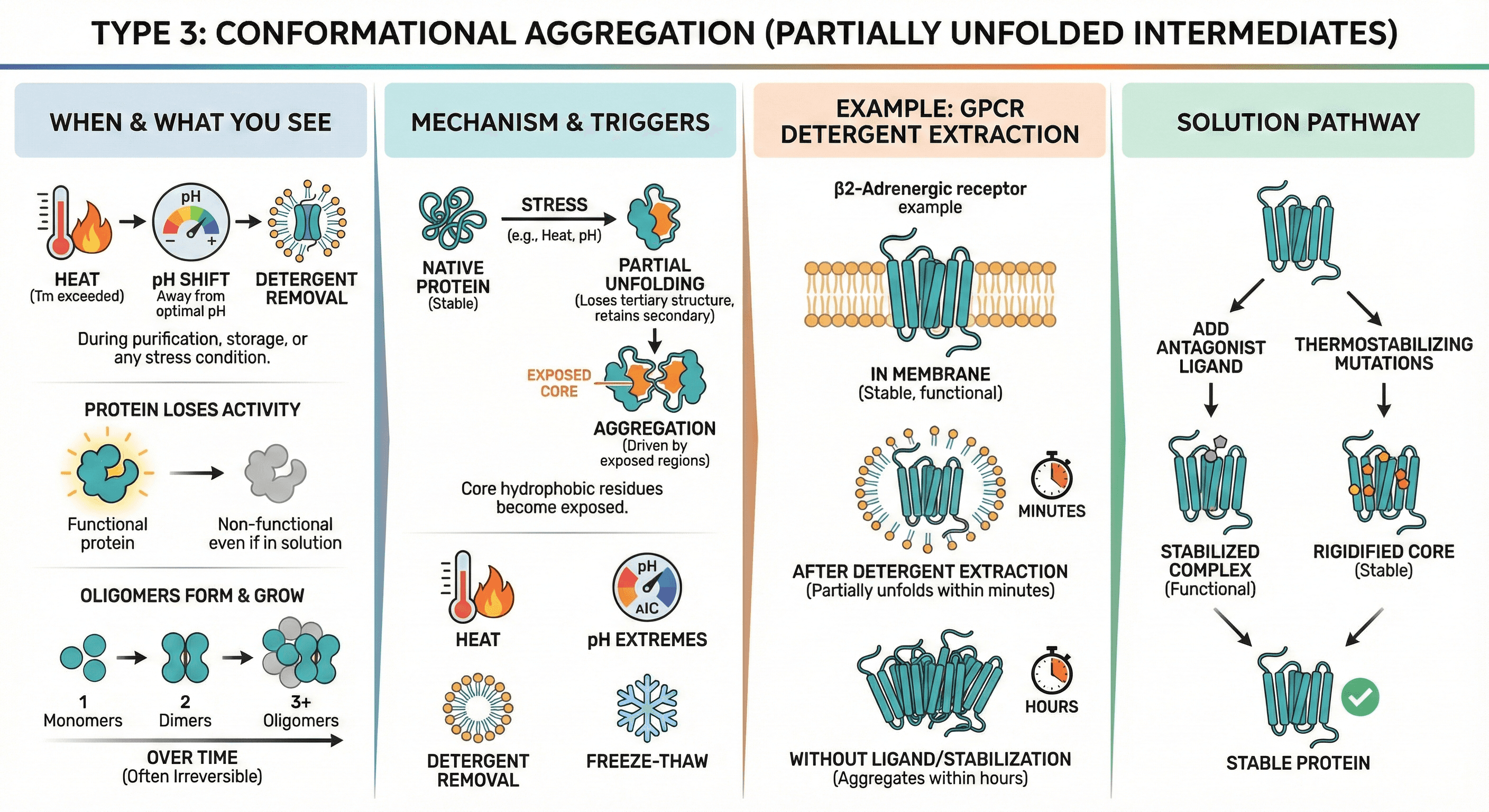

Type 3: Conformational Aggregation (Partially Unfolded Intermediates)

When it happens: During purification, storage, or any stress condition (heat, pH shift, detergent removal)

What you see:

Protein loses activity even if it stays in solution

Oligomers form (dimers, trimers) that grow over time

Often irreversible

Mechanism:

Protein partially unfolds (loses tertiary structure but retains secondary structure)

Core hydrophobic residues become exposed

These exposed regions drive aggregation

Triggers:

Heat: Tm exceeded (even briefly)

pH extremes: Away from optimal pH

Detergent removal: Membrane proteins lose stabilizing detergent

Freeze-thaw: Ice crystal formation causes local denaturation

Example: GPCR Detergent Extraction β2-Adrenergic receptor:

In membrane: Stable, functional

After detergent extraction: Partially unfolds within minutes

Without ligand/stabilization: Aggregates within hours

Solution: Add antagonist ligand (stabilizes conformation) + thermostabilizing mutations

The Molecular Basis: Why Proteins Aggregate

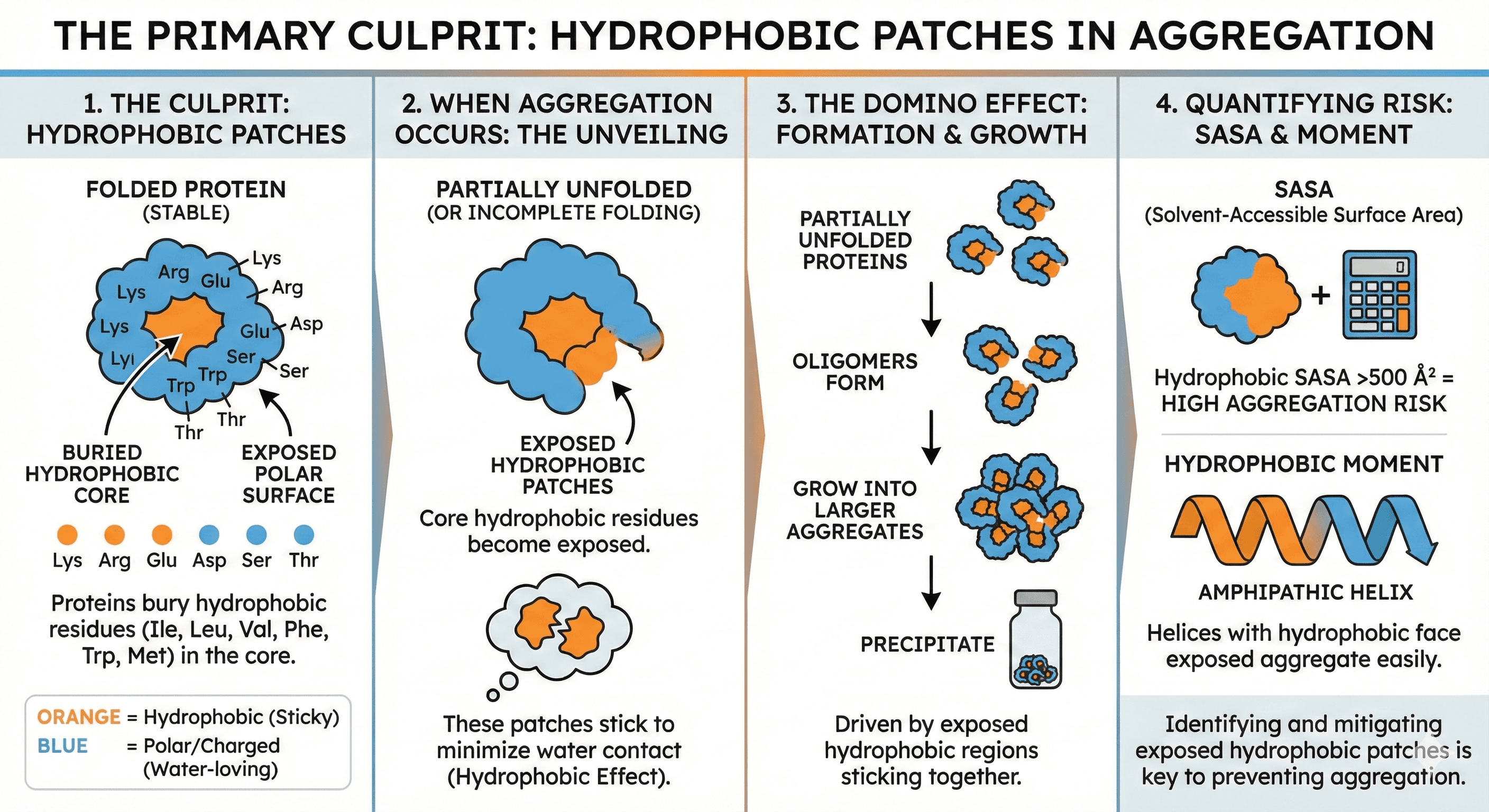

At the molecular level, aggregation is driven by one principle: Hydrophobic effect.

Hydrophobic Patches: The Primary Culprit

Proteins fold to bury hydrophobic residues (Ile, Leu, Val, Phe, Trp, Met) in the core, exposing polar/charged residues (Lys, Arg, Glu, Asp, Ser, Thr) on the surface.

When aggregation occurs:

Protein partially unfolds (or folds incompletely)

Core hydrophobic residues become exposed

These patches stick to each other to minimize water contact

Oligomers form → grow → precipitate

Quantifying exposure:

SASA (Solvent-Accessible Surface Area): Hydrophobic SASA >500 Ų = aggregation risk

Hydrophobic moment: Amphipathic helices with hydrophobic face exposed aggregate easily

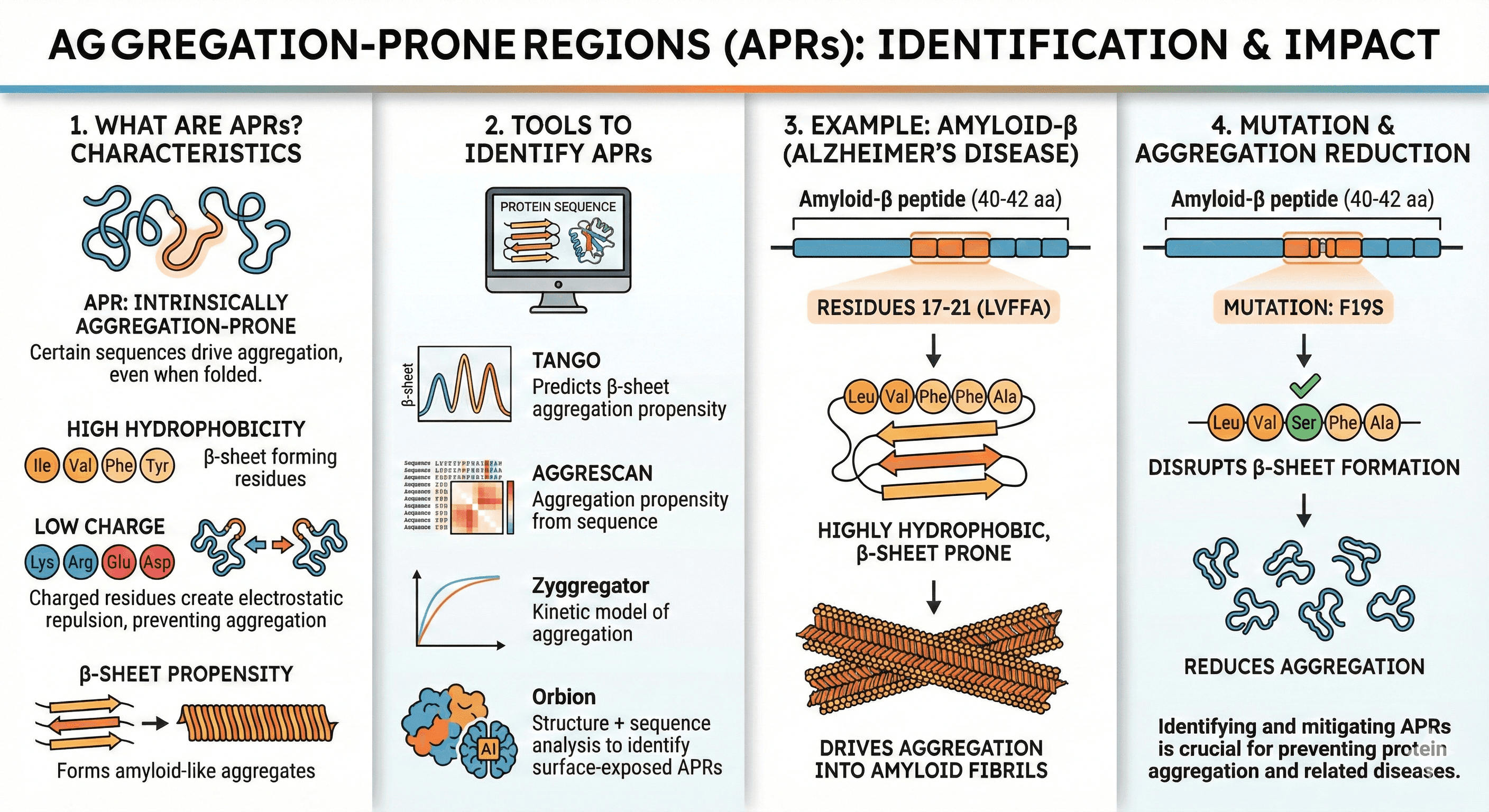

Aggregation-Prone Regions (APRs)

Certain sequences are intrinsically aggregation-prone, even in the folded state.

Characteristics of APRs:

High in hydrophobic residues (especially β-sheet forming: Ile, Val, Phe, Tyr)

Low charge (Lys, Arg, Glu, Asp prevent aggregation via electrostatic repulsion—charged residues create repulsive forces that keep protein molecules apart)

β-sheet propensity (amyloid-like aggregation)

Tools to identify APRs:

TANGO: Predicts β-sheet aggregation propensity

AGGRESCAN: Aggregation propensity from sequence

Zyggregator: Kinetic model of aggregation

Orbion: Structure + sequence analysis to identify surface-exposed APRs

Example: Amyloid-β (Alzheimer's disease) Amyloid-β peptide (40-42 amino acids):

Residues 17-21 (LVFFA): Highly hydrophobic, β-sheet prone

This region drives aggregation into amyloid fibrils

Mutations in this region (e.g., F19S) reduce aggregation

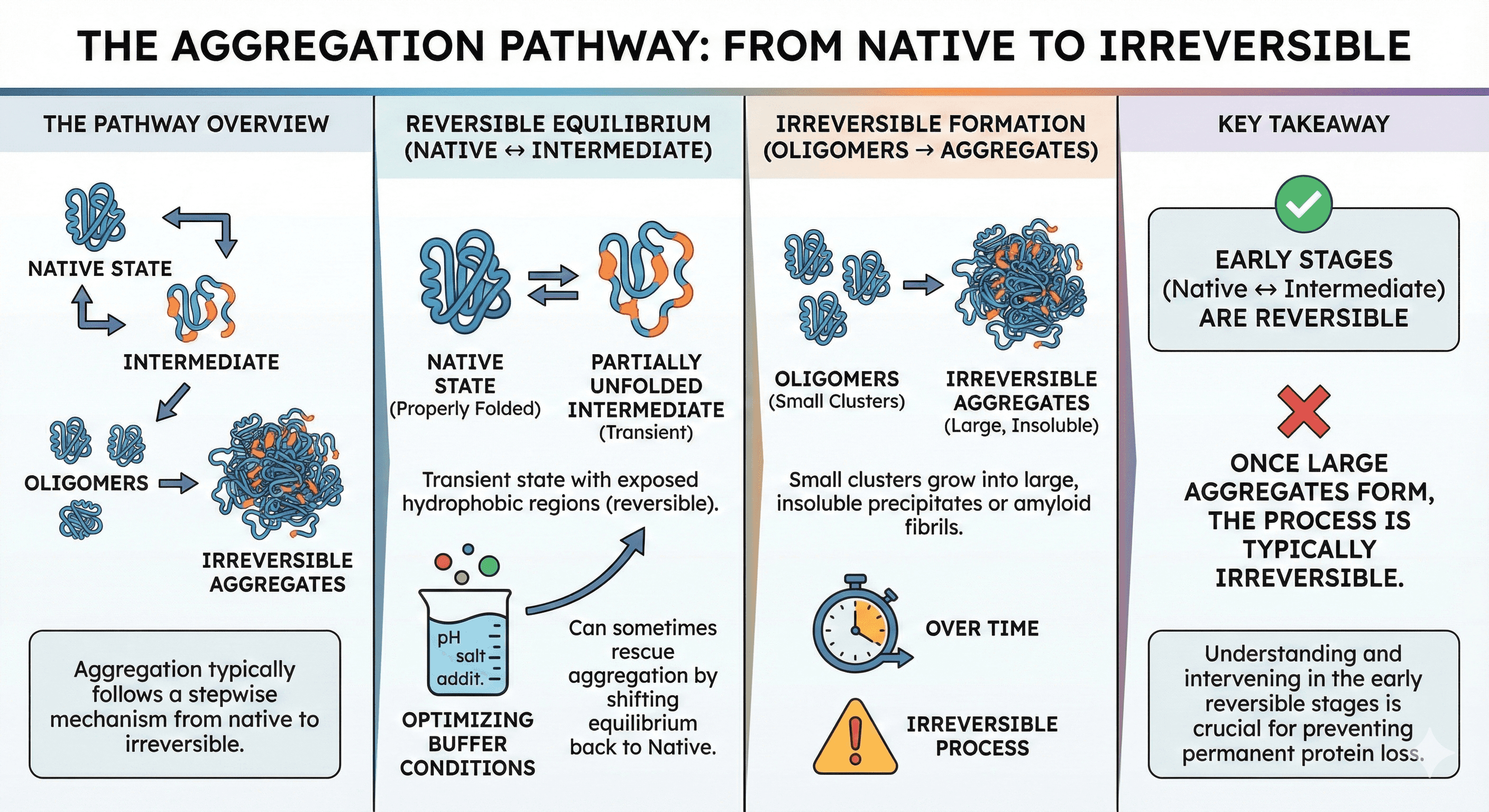

The Aggregation Pathway

Aggregation typically follows a stepwise mechanism:

Native ↔ Intermediate → Irreversible Aggregate

Native state: Properly folded, functional protein

Partially unfolded intermediate: Transient state with exposed hydrophobic regions (reversible)

Oligomers: Small clusters (dimers, trimers) that can grow

Irreversible aggregates: Large, insoluble precipitates or amyloid fibrils

The key is that early stages (native ↔ intermediate) are reversible—this is why optimizing buffer conditions can sometimes rescue aggregation. Once large aggregates form, the process is typically irreversible.

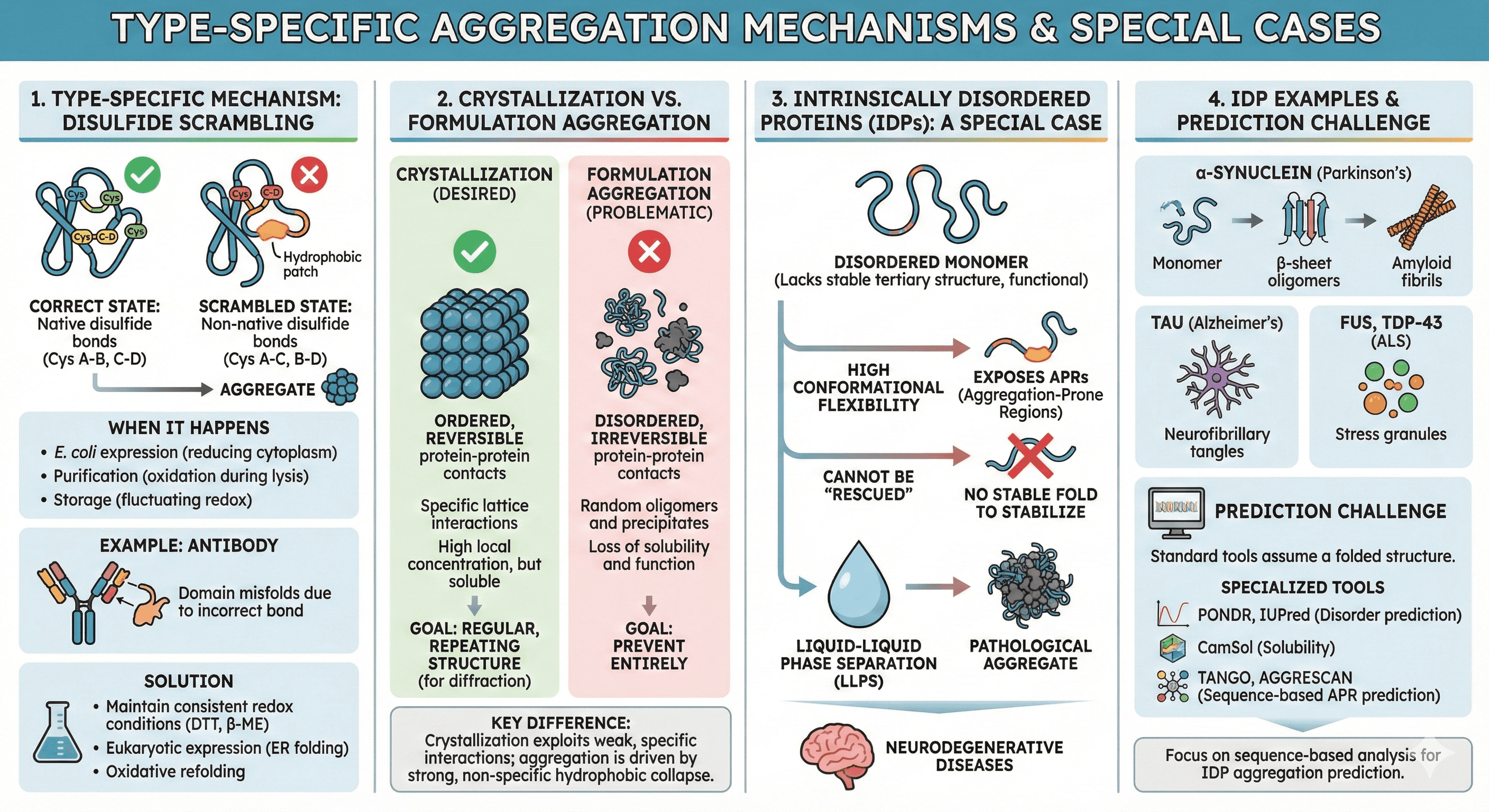

Type-Specific Aggregation Mechanisms

Disulfide scrambling (incorrect redox states): A major but often overlooked aggregation mechanism, especially for proteins with multiple cysteines:

Correct state: Native disulfide bonds (Cys A-Cys B, Cys C-Cys D)

Scrambled state: Non-native disulfide bonds (Cys A-Cys C, Cys B-Cys D)

Result: Misfolded protein with exposed hydrophobic patches → aggregation

When it happens:

During expression in E. coli (reducing cytoplasm, incorrect oxidation in periplasm)

During purification (oxidation during lysis, improper reducing conditions)

Storage with fluctuating redox conditions

Example: Antibody aggregation

IgG has 16 disulfide bonds

If even one forms incorrectly, the domain misfolds

Aggregates form through exposed hydrophobic regions

Solution:

Maintain consistent redox conditions (add DTT or β-mercaptoethanol)

For secreted proteins: Express in systems with proper oxidative folding (ER of eukaryotic cells)

Use oxidative refolding protocols if expressed in E. coli

Crystallization vs formulation aggregation:

These are distinct phenomena often confused:

Crystallization (desired):

Ordered, reversible protein-protein contacts

Specific lattice interactions

High local concentration in crystal, but soluble in mother liquor

Goal: Regular, repeating structure for diffraction

Formulation aggregation (problematic):

Disordered, irreversible protein-protein contacts

Random oligomers and precipitates

Loss of solubility and function

Goal: Prevent entirely

Key difference: Crystallization exploits weak, specific interactions; aggregation is driven by strong, non-specific hydrophobic collapse.

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs): A Special Case

IDPs lack stable tertiary structure but are functional. They present unique aggregation challenges:

Why IDPs aggregate:

High conformational flexibility exposes aggregation-prone regions

Cannot be "rescued" by stabilizing mutations (no stable fold to stabilize)

Often phase-separate into droplets (liquid-liquid phase separation, LLPS) which can mature into aggregates

Examples:

α-synuclein (Parkinson's disease): Disordered monomer → β-sheet oligomers → amyloid fibrils

Tau (Alzheimer's): Disordered in solution, aggregates into neurofibrillary tangles

FUS, TDP-43 (ALS): Phase-separate into stress granules, can aggregate pathologically

Prediction challenge: Standard tools assume a folded structure. For IDPs, use specialized tools:

PONDR, IUPred (disorder prediction)

CamSol (solubility)

Focus on sequence-based APR prediction (TANGO, AGGRESCAN)

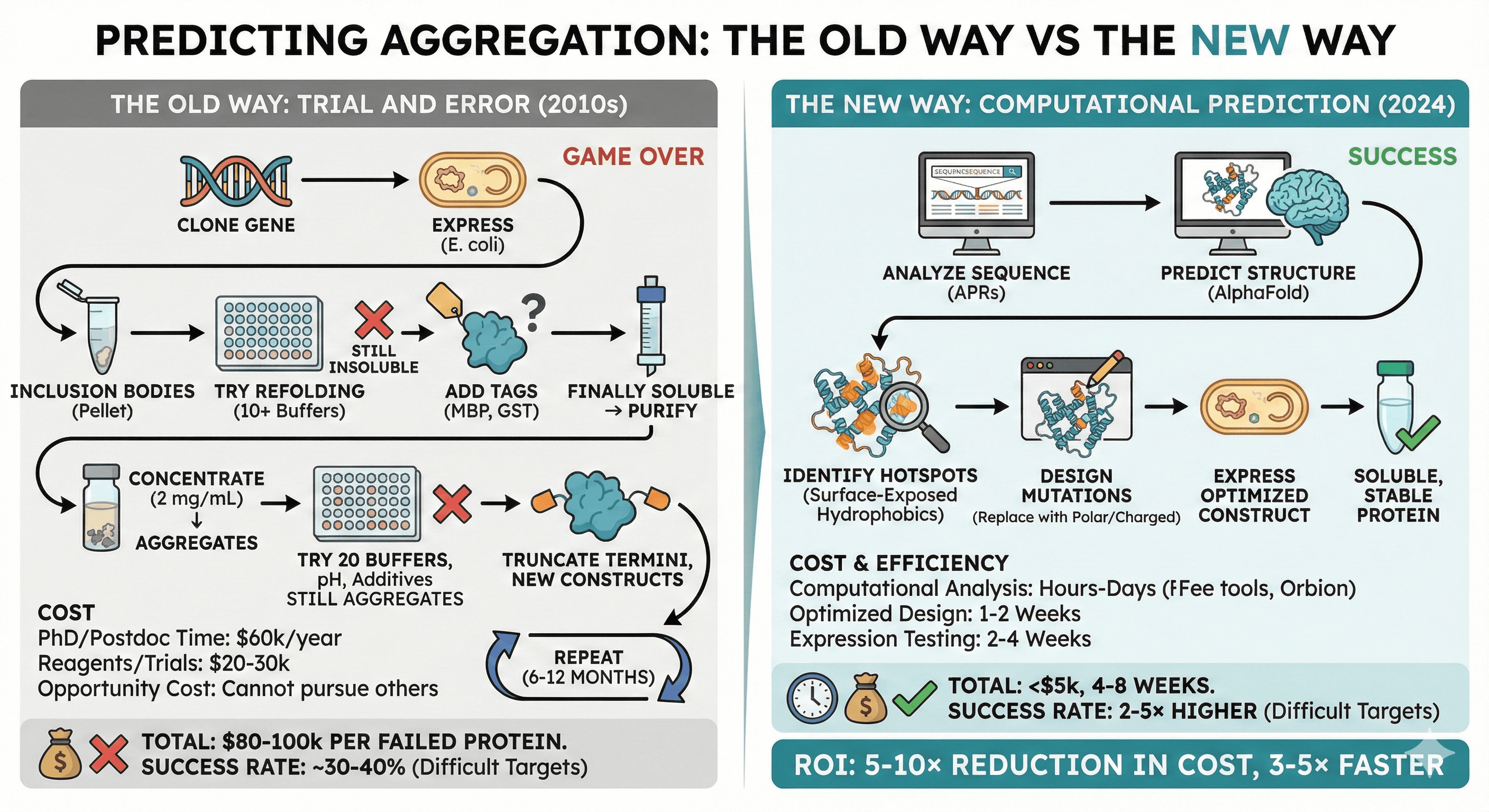

Predicting Aggregation: The Old Way vs The New Way

The Old Way: Trial and Error

Typical workflow (2010s):

Clone gene → Express in E. coli

Inclusion bodies → Try refolding (10+ buffer conditions)

Still insoluble → Try solubility tags (MBP, GST)

Finally soluble → Purify

Concentrate → Aggregates at 2 mg/mL

Try 20 buffer conditions, additives, pH values

Still aggregates → Truncate termini, try new constructs

Repeat for 6-12 months

Cost:

PhD student/postdoc time: $60k/year

Reagents, expression trials: $20-30k

Opportunity cost: Cannot pursue other targets

Total: $80-100k per failed protein

Success rate: ~30-40% for difficult targets (GPCRs, membrane proteins, intrinsically disordered proteins)

The New Way: Computational Prediction

Modern workflow (2024):

Analyze sequence for aggregation-prone regions (APRs)

Predict structure (AlphaFold if no experimental structure)

Identify hotspots: Surface-exposed hydrophobic patches

Design mutations: Replace aggregation-prone residues with polar/charged residues

Express optimized construct → Soluble, stable protein

Cost:

Computational analysis: Hours (free tools) to days (Orbion)

Optimized construct design: 1-2 weeks

Expression testing: 2-4 weeks

Total: <$5k, 4-8 weeks

Success rate improvement: 2-5× higher success rate for difficult targets (when computational design is used)

ROI: 5-10× reduction in cost, 3-5× faster

Tools for Aggregation Prediction

Sequence-Based Tools (No Structure Required)

1. AGGRESCAN

What it does: Scans sequence for aggregation-prone regions

Output: Aggregation propensity score per residue

Best for: Quick initial screen

Limitation: Doesn't account for burial in folded structure

2. TANGO

What it does: Predicts β-sheet aggregation (amyloid-like)

Output: Aggregation rate constants

Best for: Identifying amyloidogenic segments

Limitation: Focused on β-sheet aggregation (misses other types)

3. Zyggregator

What it does: Kinetic model of aggregation based on physicochemical properties

Output: Aggregation rate at different concentrations/temperatures

Best for: Predicting concentration dependence

Limitation: Empirical model, less accurate for membrane proteins

Structure-Based Tools (Requires 3D Structure)

4. AGGRESCAN3D

What it does: Maps aggregation propensity onto 3D structure

Output: Surface-exposed aggregation-prone patches

Best for: Identifying regions to mutate

Limitation: Requires accurate structure

5. CamSol (Cambridge Solubility Predictor)

What it does: Predicts protein solubility from structure

Output: Solubility score, identifies problematic residues

Best for: Antibody and therapeutic protein optimization

Limitation: Trained mostly on antibodies

6. Spatial Aggregation Propensity (SAP)

What it does: Analyzes clustering of hydrophobic residues on surface

Output: Hotspot map

Best for: Detecting non-obvious aggregation mechanisms

AI/ML Platforms (Structure + Sequence + Context)

7. Orbion

What it does:

Predicts aggregation hotspots from AlphaFold or experimental structure

Suggests specific mutations to reduce aggregation (with ΔΔG predictions)

Integrates with stability predictions (ensure mutations don't destabilize fold)

Recommends expression system based on aggregation risk

Output:

Aggregation risk score

Residue-level hotspot map

Mutation recommendations (e.g., "L47S reduces aggregation 80%, ΔΔG = +0.3 kcal/mol, maintains stability")

Best for: Rescue strategies for failed targets, therapeutic antibody optimization

Advantage: Combines multiple prediction methods + experimental validation data

How to Fix Aggregation: The Rescue Toolkit

Once you know why your protein aggregates, you can fix it. Here are the five main strategies:

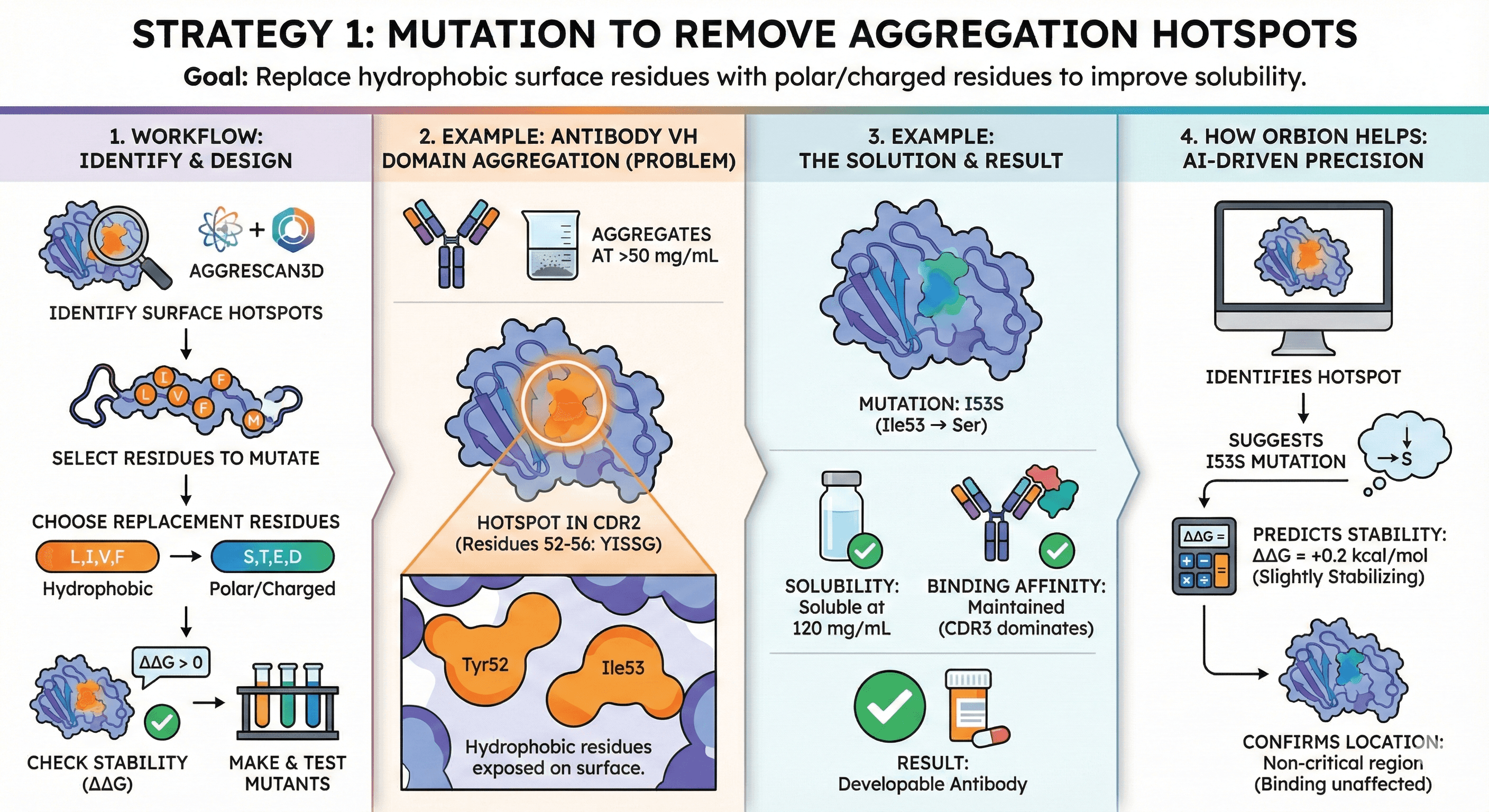

Strategy 1: Mutation to Remove Aggregation Hotspots

Goal: Replace hydrophobic surface residues with polar/charged residues

Workflow:

Identify surface-exposed hydrophobic patches (AGGRESCAN3D, Orbion)

Select residues to mutate (prioritize Leu, Ile, Val, Phe, Met on surface)

Choose replacement residues:

Hydrophobic → Polar: Leu → Ser, Ile → Thr

Hydrophobic → Charged: Val → Glu, Phe → Asp (if structure allows)

Check that mutation doesn't destabilize fold (Orbion ΔΔG prediction, or Rosetta)

Make 2-3 mutants, test in parallel

Example: Antibody VH Domain Aggregation

Problem:

Therapeutic antibody aggregates above 50 mg/mL

AGGRESCAN3D identifies hotspot in CDR2 (VH residues 52-56: YISSG)

Hydrophobic Tyr52 and Ile53 exposed on surface

Solution:

Mutate Ile53 → Ser (I53S)

Test: I53S variant remains soluble at 120 mg/mL

Binding affinity: Maintained (CDR3 dominates binding)

Result: Developable antibody

How Orbion helps:

Identifies the hotspot

Suggests I53S mutation

Predicts ΔΔG = +0.2 kcal/mol (slightly stabilizing)

Confirms mutation is in non-critical region (binding affinity unaffected)

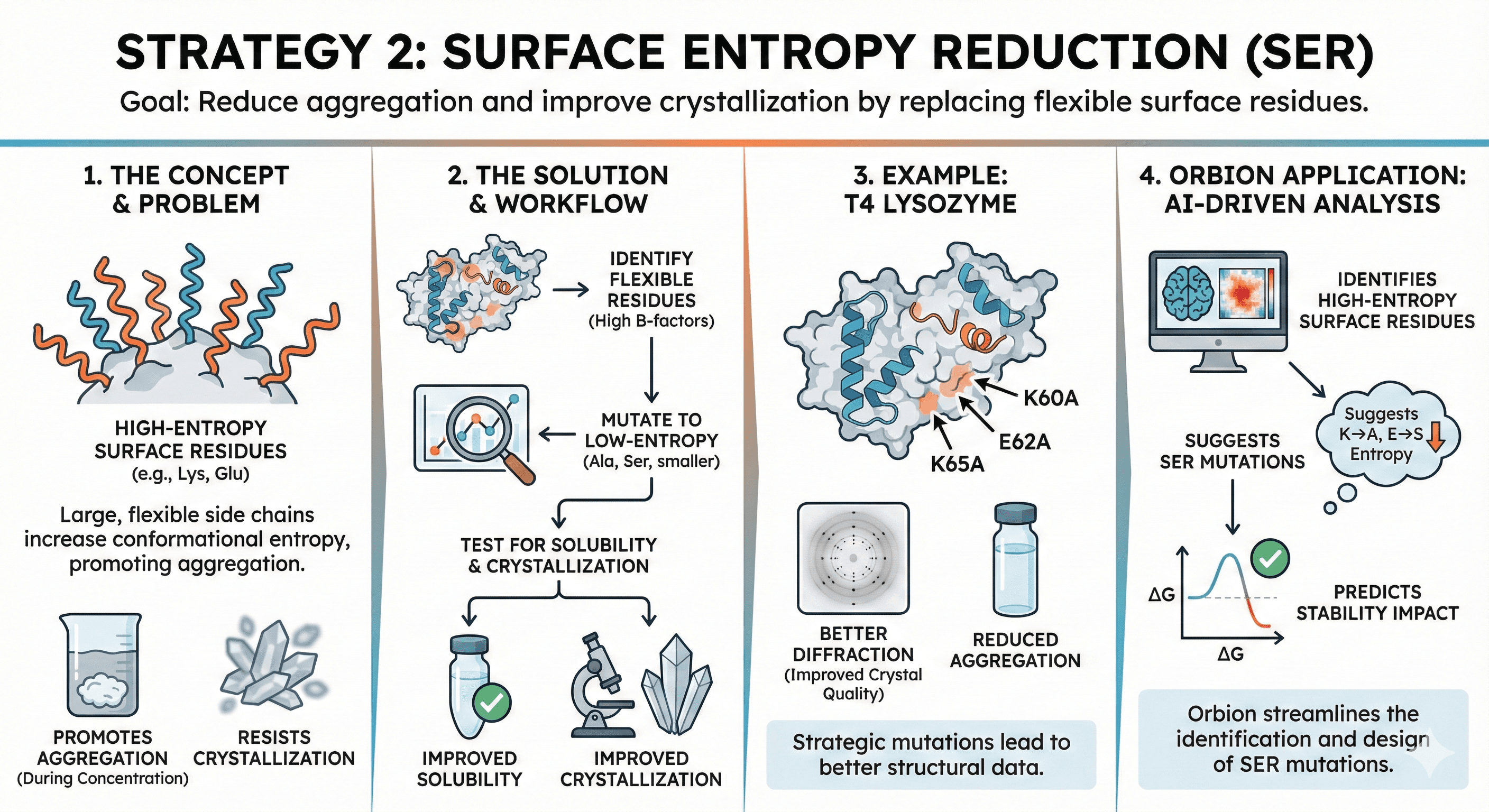

Strategy 2: Surface Entropy Reduction (SER)

Concept: High-entropy surface residues (Lys, Glu with flexible side chains) can promote aggregation by increasing conformational entropy. Replacing them with low-entropy residues (Ala, Ser) reduces aggregation and improves crystallization.

When to use: Proteins that aggregate during concentration or resist crystallization

How it works:

Identify surface Lys or Glu residues with high B-factors (flexible)

Mutate to Ala or Ser (smaller, less flexible)

Test for solubility and crystallization

Example: T4 Lysozyme

Mutation: K60A, E62A, K65A

Result: Improved crystal quality (better diffraction), reduced aggregation

Orbion:

Identifies high-entropy surface residues

Suggests SER mutations

Predicts impact on stability

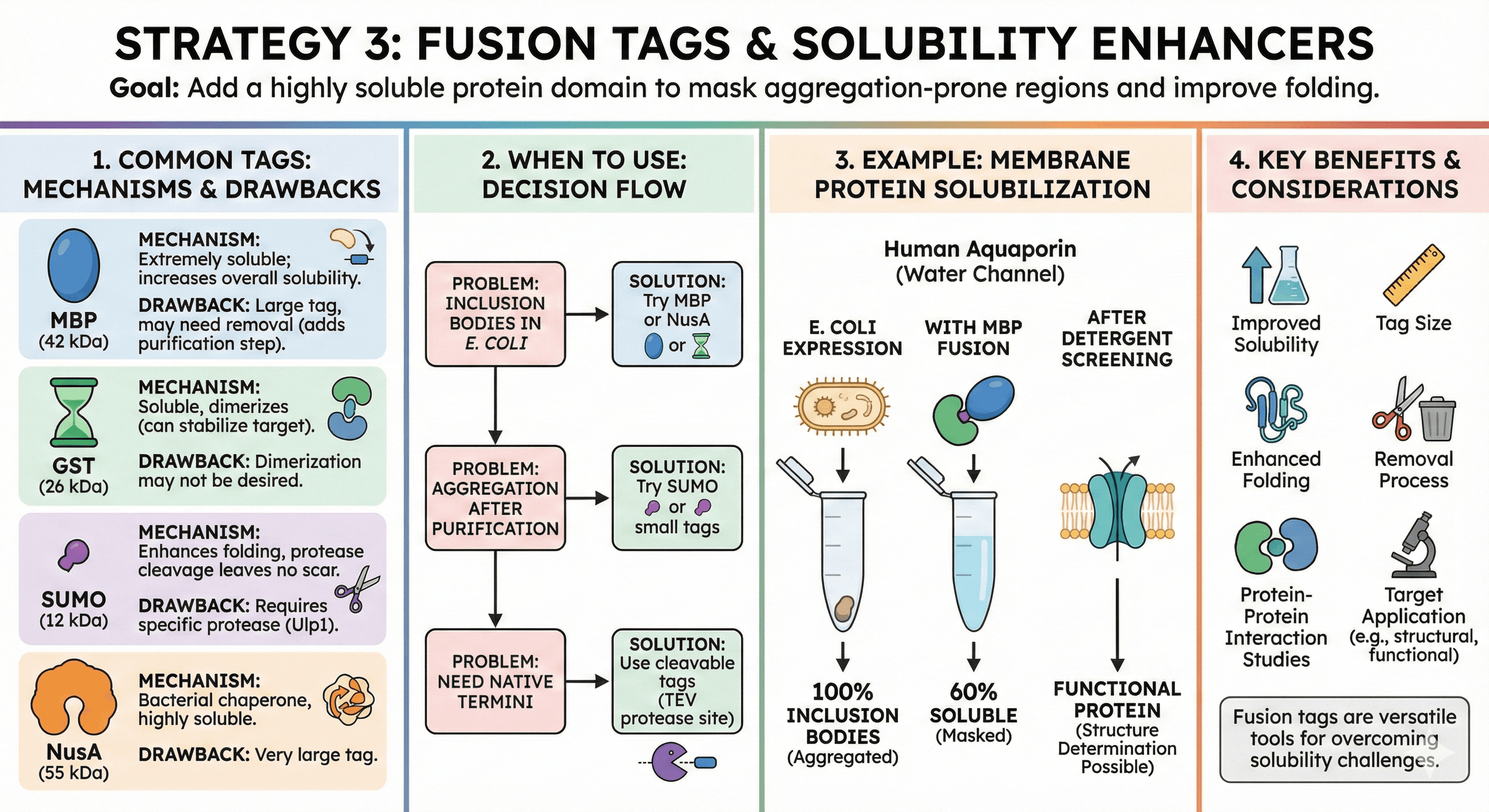

Strategy 3: Fusion Tags & Solubility Enhancers

Goal: Add a highly soluble protein domain to mask aggregation-prone regions

Common tags:

MBP (Maltose Binding Protein) - 42 kDa

Mechanism: MBP is extremely soluble; fusing it to your protein increases overall solubility

Best for: Cytoplasmic proteins, difficult-to-express proteins

Drawback: Large tag, may need removal (adds purification step)

GST (Glutathione S-Transferase) - 26 kDa

Mechanism: Soluble, dimerizes (can help stabilize target protein)

Best for: Protein-protein interaction studies, pull-down assays

Drawback: Dimerization may not be desired

SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier) - 12 kDa

Mechanism: Enhances folding, protease cleavage leaves no scar

Best for: Proteins requiring native N-terminus

Drawback: Requires specific protease (Ulp1)

NusA - 55 kDa

Mechanism: Bacterial chaperone, highly soluble

Best for: Proteins prone to inclusion bodies

Drawback: Very large tag

When to use:

Inclusion bodies in E. coli → Try MBP or NusA

Aggregation after purification → Try SUMO or small tags

Need native termini → Use cleavable tags (TEV protease site)

Example: Membrane Protein Solubilization Human aquaporin (water channel):

In E. coli: 100% inclusion bodies

With MBP fusion: 60% soluble

After detergent screening: Functional protein

Result: Structure determination possible

Strategy 4: Expression System Optimization

Principle: Different organisms have different folding machinery, chaperones, and PTM capabilities. Switching systems can solve aggregation.

Decision tree:

E. coli (bacteria):

Pros: Fast, cheap, high yield

Cons: No eukaryotic chaperones, no glycosylation, limited disulfide formation

Best for: Simple cytoplasmic proteins, no PTMs needed

Pichia pastoris (yeast):

Pros: Eukaryotic folding, some glycosylation, disulfide bonds

Cons: High-mannose glycans (non-human), lower yield than E. coli

Best for: Secreted proteins, simple glycoproteins

Sf9/Hi5 (insect cells):

Pros: Good folding, complex disulfides, some glycosylation

Cons: Minimal sialylation, expensive

Best for: GPCRs, complex membrane proteins

HEK293/CHO (mammalian cells):

Pros: Native-like folding, full glycosylation, correct PTMs

Cons: Slow, expensive, lower yield

Best for: Therapeutic antibodies, membrane proteins requiring native PTMs

Example: GPCR Expression β2-Adrenergic receptor:

E. coli: Inclusion bodies (100%)

Pichia: Partially functional (20% yield)

Sf9 (insect cells): Functional receptor (60% yield)

Choice: Insect cells (balance of yield and function)

How Orbion helps:

Analyzes PTM requirements (glycosylation, phosphorylation)

Recommends expression system

Example: "This protein requires N-glycosylation at Asn120 → Use insect or mammalian cells"

Strategy 5: Buffer & Formulation Optimization

Goal: Optimize solution conditions to prevent aggregation

Key variables:

1. pH

Principle: Proteins aggregate near their pI (isoelectric point) due to reduced charge repulsion

Solution: Work at pH 1-2 units away from pI

Tool: Calculate pI (ExPASy ProtParam), test pH 5.5, 6.5, 7.5, 8.5

2. Salt concentration

Principle: Moderate salt (50-150 mM NaCl) screens charge interactions, reduces aggregation

Too low salt: Charge-charge aggregation

Too high salt: Salting-out effect (protein precipitates)

Optimal: 100-150 mM NaCl for most proteins

3. Additives

Arginine (50-500 mM): Suppresses aggregation (mechanism unclear, likely disrupts hydrophobic interactions)

Glycerol (5-20%): Stabilizes native state, reduces unfolding

Sucrose/Trehalose (5-10%): Osmolytes, protect against freeze-thaw

Detergents (membrane proteins): Maintain solubility (DDM, LMNG, amphipols)

4. Temperature

Cold storage (4°C): Slows aggregation kinetics

Flash-freezing: Rapid cooling minimizes ice crystal damage

Avoid freeze-thaw: Each cycle causes partial unfolding

Example: Antibody Formulation Optimization Monoclonal antibody aggregating at >100 mg/mL:

Initial buffer: PBS (pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl)

Aggregates at 120 mg/mL

Optimization screen:

pH: Test 5.5, 6.5, 7.5, 8.5 → Best at pH 6.0

Additives: Add 10 mM arginine + 5% sucrose

Result: Stable at 150 mg/mL for 6 months

Case Study: Rescuing an Aggregation-Prone Therapeutic Antibody

The Challenge

Target: Therapeutic monoclonal antibody (IgG1) for cancer Problem: Aggregates above 50 mg/mL (subcutaneous formulation requires >100 mg/mL) Timeline: 8 months in, Phase I trials delayed

The Investigation

Step 1: Identify aggregation mechanism

DLS (dynamic light scattering): Oligomers form at >30 mg/mL

SEC-MALS: High-molecular-weight species (dimers, trimers)

Conclusion: Concentration-dependent, reversible aggregation

Step 2: Computational prediction

Run AGGRESCAN3D on antibody structure

Hotspot identified: VH CDR2 (residues 52-56)

Hydrophobic patch (Tyr52, Ile53, Phe55) exposed on surface

Step 3: Rational mutagenesis

Design mutations:

I53S (Ile → Ser)

F55T (Phe → Thr)

Double mutant: I53S/F55T

Predict ΔΔG (stability): Orbion predicts +0.3 kcal/mol (slightly stabilizing)

The Solution

Step 4: Experimental validation

Express I53S, F55T, and I53S/F55T variants

Test solubility at 100, 150, 200 mg/mL

Results:

Wild-type: Aggregates at 60 mg/mL

I53S: Soluble to 130 mg/mL

F55T: Soluble to 110 mg/mL

I53S/F55T: Soluble to 180 mg/mL ✓

Step 5: Functional validation

Binding affinity (SPR): I53S/F55T binds with same Kd as wild-type

ADCC activity: Maintained

Pharmacokinetics (mouse model): Half-life unchanged

Outcome:

Developable antibody formulation (150 mg/mL)

Phase I trials resumed

Time saved: 12 months (avoided complete redesign)

The Economics of Aggregation Prevention

Cost of Failure

Academic target:

1 year of postdoc time: $60k

Reagents: $20k

Opportunity cost: Missed publications, delayed graduation

Total: $80k

Therapeutic antibody:

Discovery program: $10-20M

If aggregation detected late (Phase I): $50-100M wasted

Delay to market: 1-2 years = $500M-1B in lost revenue

ROI of Computational Prediction

Upfront investment:

Orbion subscription: $X/month

Computational time: 1-2 days

Savings:

Avoid 6-12 months of trial-and-error

Test 2-3 designed mutants instead of 50 random constructs

Increase success rate from 30% → 70%

ROI: 10-20× return on investment

Practical Checklist: Preventing Aggregation

Before Expression

[ ] Run aggregation prediction (AGGRESCAN, Orbion)

[ ] Check pI (avoid working near pI)

[ ] Identify surface hydrophobic patches

[ ] Design 2-3 mutants if hotspots found

[ ] Choose expression system based on PTM needs

During Expression

[ ] Small-scale test (don't commit to 10L culture immediately)

[ ] Check soluble vs insoluble fractions (SDS-PAGE)

[ ] If insoluble: Try 16°C expression, co-express chaperones, or add fusion tag

[ ] If soluble but low yield: Optimize induction conditions (IPTG concentration, time)

During Purification

[ ] Keep protein cold (4°C throughout)

[ ] Add stabilizers to buffer (glycerol 10%, DTT if cysteines present)

[ ] Avoid high protein concentrations early (dilute after elution)

[ ] Run SEC (size-exclusion chromatography) to remove aggregates

During Storage

[ ] Aliquot and flash-freeze (minimize freeze-thaw cycles)

[ ] Add cryoprotectants (10% glycerol or 5% trehalose)

[ ] Store at -80°C (more stable than -20°C)

[ ] For long-term: Lyophilize (freeze-dry)

If It Still Aggregates

[ ] Try fusion tag (MBP, SUMO)

[ ] Switch expression system (E. coli → yeast → insect → mammalian)

[ ] Revisit construct design (truncate disordered regions)

[ ] Screen formulation buffers (pH, salt, additives)

The Future: AI-Driven Aggregation Rescue

Machine learning models trained on millions of protein sequences and structures are making aggregation prediction more accurate.

Emerging Tools

1. AlphaFold confidence scores as aggregation predictors

Low pLDDT regions (<70) often correlate with aggregation-prone loops

Not explicit aggregation prediction, but useful heuristic

2. Generative models for solubility optimization

Tools like ProteinMPNN can redesign surface to maximize solubility

Generate variants with same function, improved expression

3. Deep learning scoring functions

Train on experimental aggregation data

Predict aggregation rate at different concentrations

4. Integration platforms (like Orbion)

Combine structure, sequence, PTM prediction, stability

Suggest complete rescue strategy (mutations + expression system + formulation)

The Bottom Line

Protein aggregation is not random bad luck. It is a predictable, solvable engineering problem.

The old paradigm: Express → Hope it works → Troubleshoot for months

The new paradigm: Predict → Design → Express optimized construct → Success

With modern computational tools, you can:

Predict aggregation before expressing anything

Design rescue mutations to remove hotspots

Choose the right expression system based on PTM and folding needs

Optimize formulation computationally before experimental screening

The payoff:

2-5× improvement in success rates

3-5× faster timelines

10× cost reduction

The difference between a "difficult protein" and a "successful structure" is often just 1-2 well-placed mutations identified by prediction tools like Orbion.

Aggregation used to be the graveyard of protein projects. Today, it's dramatically reduced—if you use the right tools. While not every aggregation problem can be solved computationally, the success rate has improved dramatically, transforming once-intractable targets into achievable goals.

Ready to Rescue Your Aggregating Protein?

If you have a protein that aggregates during expression, purification, or storage, Orbion can help identify why and suggest how to fix it.

Orbion provides:

Aggregation hotspot prediction from structure or sequence

Specific mutation recommendations (with ΔΔG stability predictions)

Expression system selection based on PTM requirements

Formulation optimization guidance