Blog

Why Your Protein Doesn't Express in E. coli (When It Should)

Jan 19, 2026

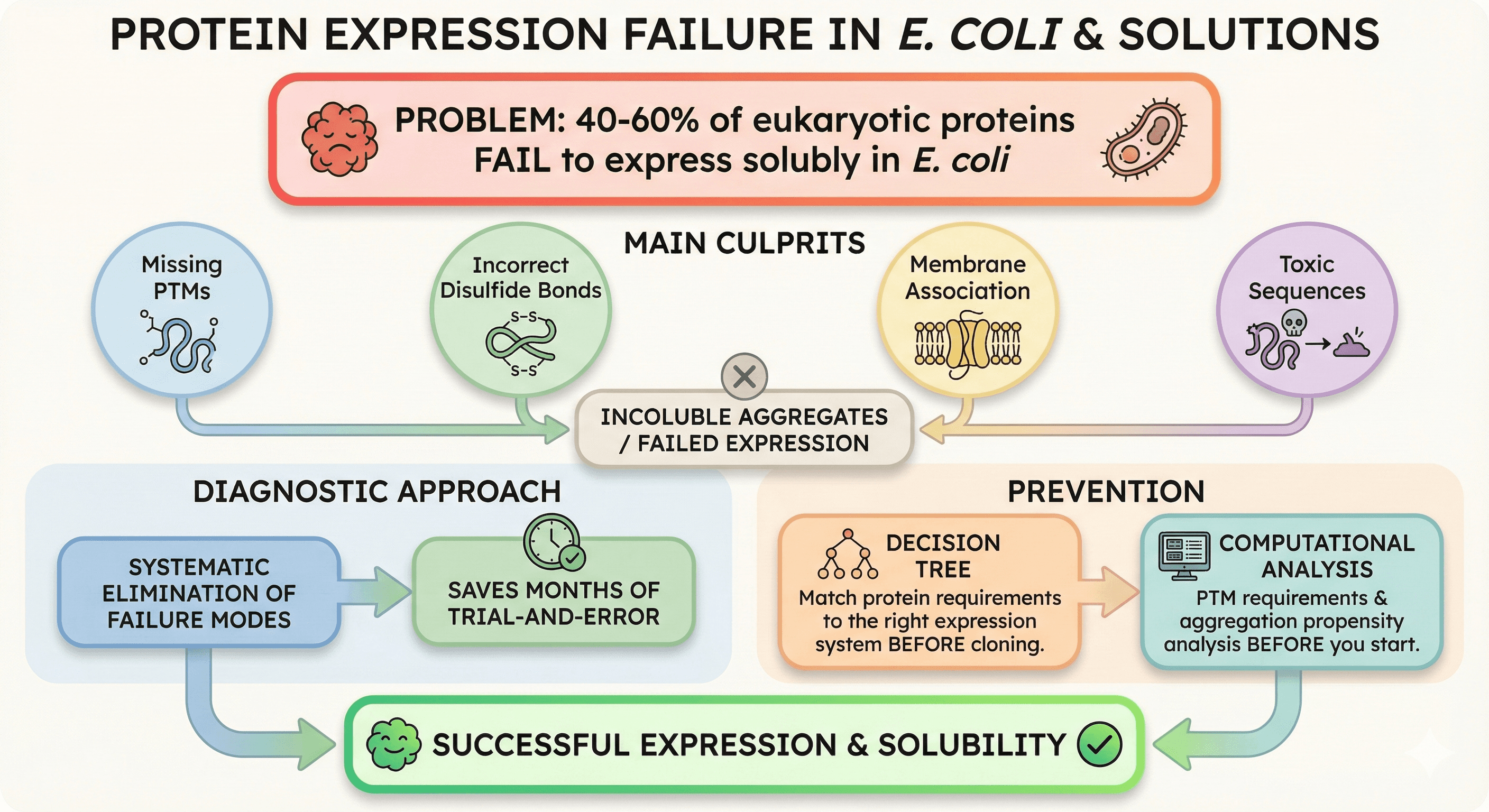

You cloned the gene. Sequence-verified the construct. Transformed competent cells. Induced with IPTG. And got... nothing. No band on SDS-PAGE. Or worse—a beautiful band in the insoluble fraction, mocking you from the pellet. You've just joined the club that every protein biochemist eventually joins: the E. coli expression failure club.

Here's the thing: E. coli is supposed to be the workhorse. Fast, cheap, scalable. But for 40-60% of eukaryotic proteins, it simply doesn't work (Structural Genomics Consortium data). The question is: why yours?

Key Takeaways

40-60% of eukaryotic proteins fail to express solubly in E. coli

Main culprits: Missing PTMs, incorrect disulfide bonds, membrane association, toxic sequences

Diagnostic approach: Systematic elimination of failure modes saves months of trial-and-error

Decision tree: Match your protein's requirements to the right expression system before cloning

Prevention: Computational analysis of PTM requirements and aggregation propensity before you start

The E. coli Paradox

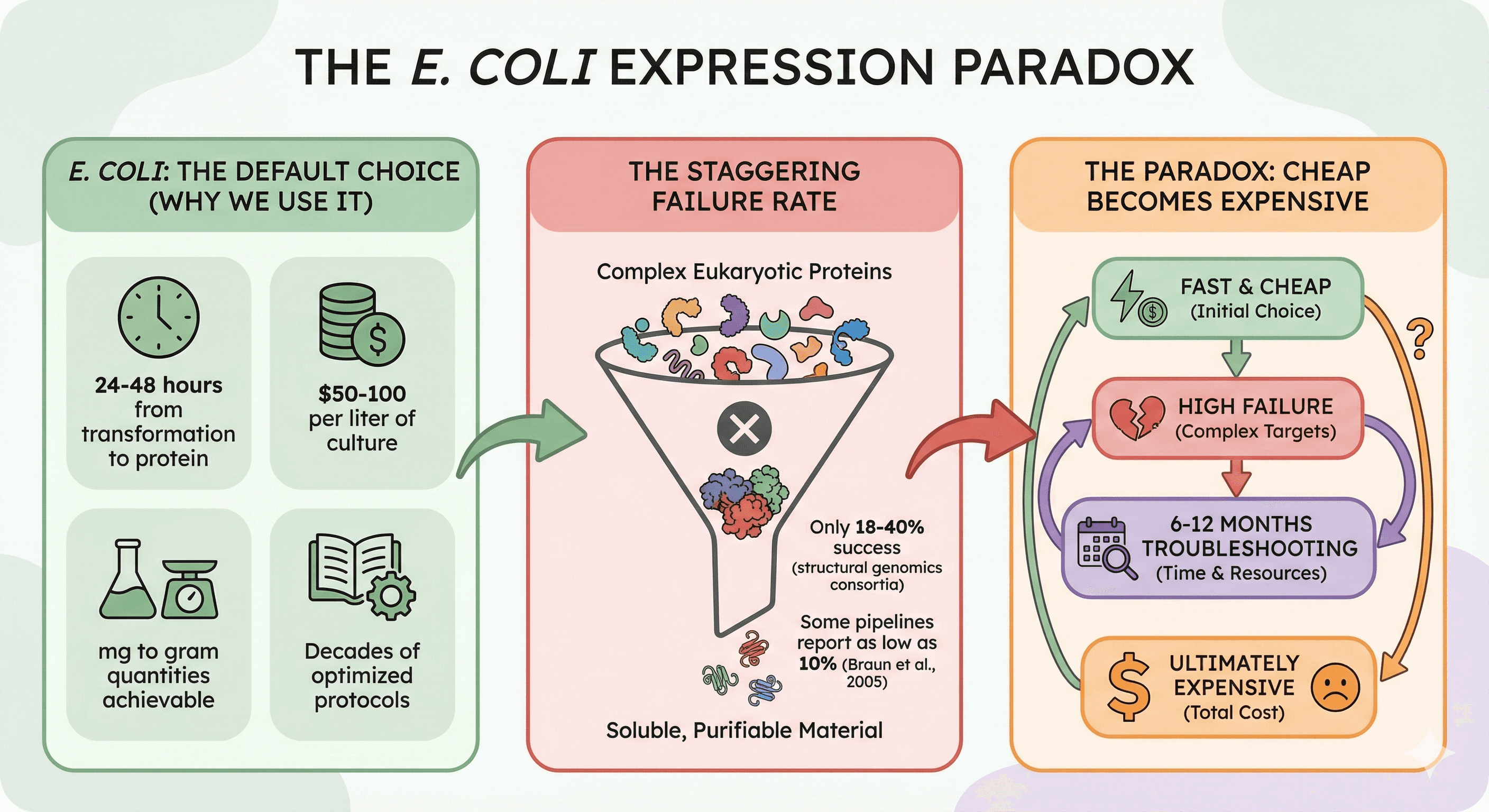

E. coli remains the default choice for recombinant protein expression. And for good reason:

24-48 hours from transformation to protein

$50-100 per liter of culture

mg to gram quantities achievable

Decades of optimized protocols

Yet the failure rate for complex eukaryotic proteins is staggering. Structural genomics consortia report that only 18-40% of human proteins yield soluble, purifiable material from bacterial expression, with some pipelines reporting as low as 10% success for eukaryotic targets (Braun et al., 2005).

The paradox: We keep using E. coli because it's fast and cheap, then spend 6-12 months troubleshooting when it fails. The "cheap" option becomes the expensive one.

The Five Reasons Your Protein Failed

When E. coli expression fails, it's almost always one of these five problems. Diagnosing which one saves you from random troubleshooting.

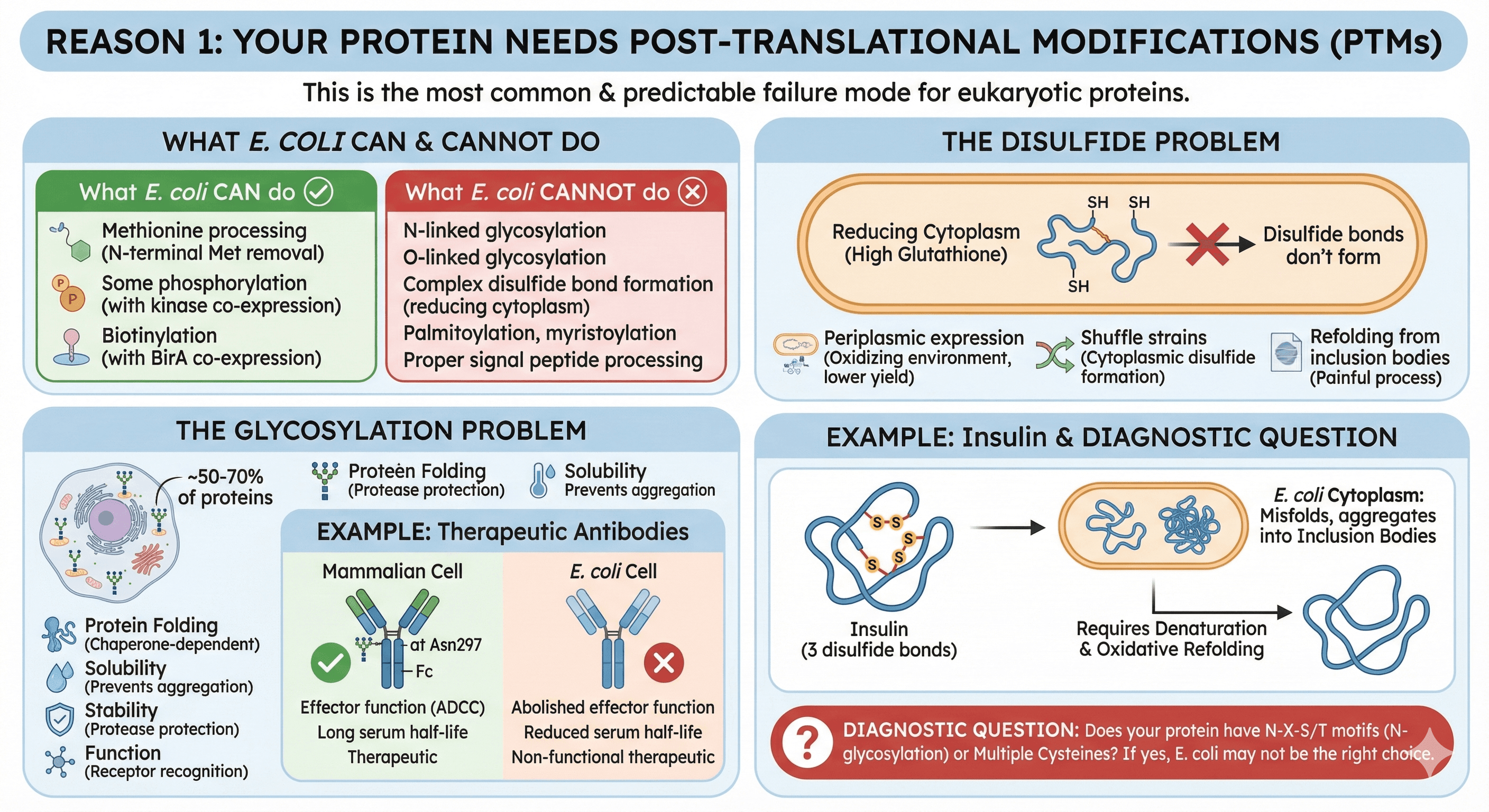

Reason 1: Your Protein Needs Post-Translational Modifications

This is the most common failure mode for eukaryotic proteins, and the most predictable.

What E. coli can do:

Methionine processing (N-terminal Met removal)

Some phosphorylation (if you co-express the kinase)

Biotinylation (with BirA co-expression)

What E. coli cannot do:

N-linked glycosylation

O-linked glycosylation

Complex disulfide bond formation (cytoplasm is reducing)

Palmitoylation, myristoylation

Proper signal peptide processing

The glycosylation problem:

Approximately 50% of human proteins are glycosylated, with some estimates suggesting over 70% of the eukaryotic secretory proteome undergoes glycosylation (Apweiler et al., 1999). Glycans aren't just decorations—they're often essential for:

Protein folding (glycan-dependent chaperones like calnexin)

Solubility (hydrophilic glycans prevent aggregation)

Stability (protection from proteases)

Function (receptor recognition, cell signaling)

Example: Therapeutic antibodies

IgG antibodies require N-glycosylation at Asn297 in the Fc region (Wang et al., 2017). Without it:

Effector function (ADCC) is abolished or significantly reduced

Serum half-life drops dramatically

The protein may still fold, but it's non-functional therapeutically

Express an antibody in E. coli and you get protein. But it's not a therapeutic.

The disulfide problem:

E. coli's cytoplasm is reducing (high glutathione, thioredoxin). Disulfide bonds don't form. Options:

Periplasmic expression (oxidizing environment, but lower yield)

Shuffle strains (cytoplasmic disulfide formation)

Refolding from inclusion bodies (works, but painful)

Example: Insulin

Insulin has 3 disulfide bonds (two interchain and one intrachain) (Baeshen et al., 2014). Express in E. coli cytoplasm:

Protein misfolds immediately

Aggregates into inclusion bodies

Requires denaturation and oxidative refolding

This is doable—the majority of recombinant insulin therapeutics are produced from E. coli inclusion bodies—but it's a specialized process requiring careful refolding optimization, not a quick expression test.

Diagnostic question: Does your protein have N-X-S/T motifs (potential N-glycosylation sites)? Multiple cysteines? If yes, E. coli may not be the right choice.

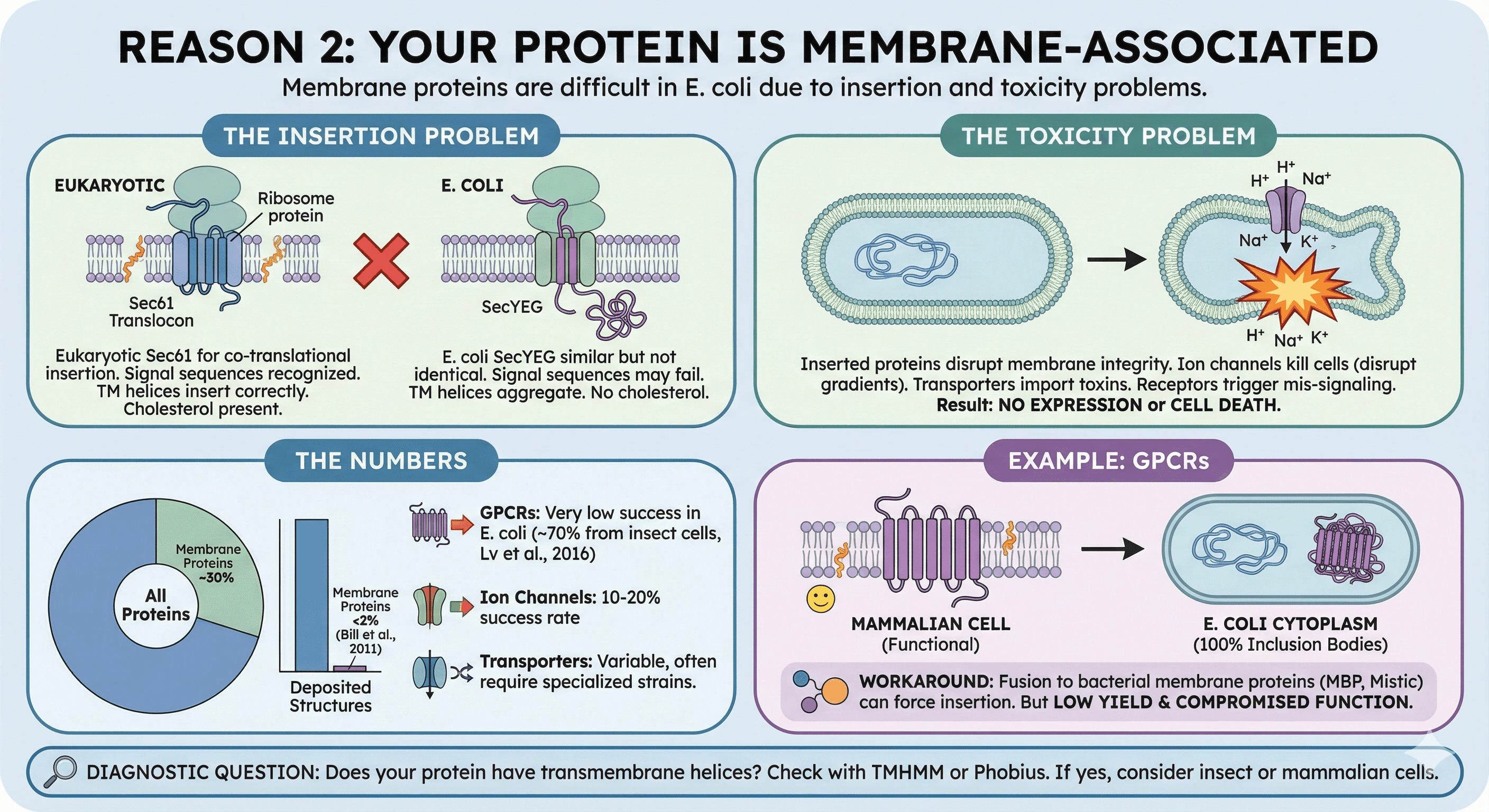

Reason 2: Your Protein Is Membrane-Associated

Membrane proteins are notoriously difficult in E. coli. Not because bacteria lack membranes, but because:

The insertion problem:

Eukaryotic membrane proteins use the Sec61 translocon for co-translational insertion. E. coli uses SecYEG. The machinery is similar but not identical:

Signal sequences may not be recognized

Transmembrane helices may not insert correctly

Lipid composition differs (no cholesterol in bacteria)

The toxicity problem:

Membrane proteins that do insert can disrupt E. coli's membrane integrity:

Ion channels can kill cells by disrupting electrochemical gradients

Transporters can import toxic compounds

Receptors can trigger inappropriate signaling

The result: Either no expression (cells suppress the toxic protein) or cell death (you get no cells to harvest).

The numbers:

Membrane proteins represent ~30% of all proteins yet account for less than 2% of deposited structures (Bill et al., 2011):

GPCRs in E. coli: Very low success rate for functional protein; most GPCR structures (~70%) come from insect cells (Lv et al., 2016)

Ion channels: 10-20% success rate

Transporters: Variable, often require specialized strains

Example: GPCRs

G-protein coupled receptors are 7-transmembrane proteins. In E. coli:

No mammalian membrane insertion machinery

No appropriate lipid environment (needs cholesterol for many GPCRs)

Hydrophobic transmembrane helices aggregate in cytoplasm

Result: 100% inclusion bodies

The workaround: Fusion to bacterial membrane proteins (MBP, Mistic) can sometimes force membrane insertion. But yield is low and function is often compromised.

Diagnostic question: Does your protein have transmembrane helices? Check with TMHMM or Phobius. If yes, consider insect or mammalian cells.

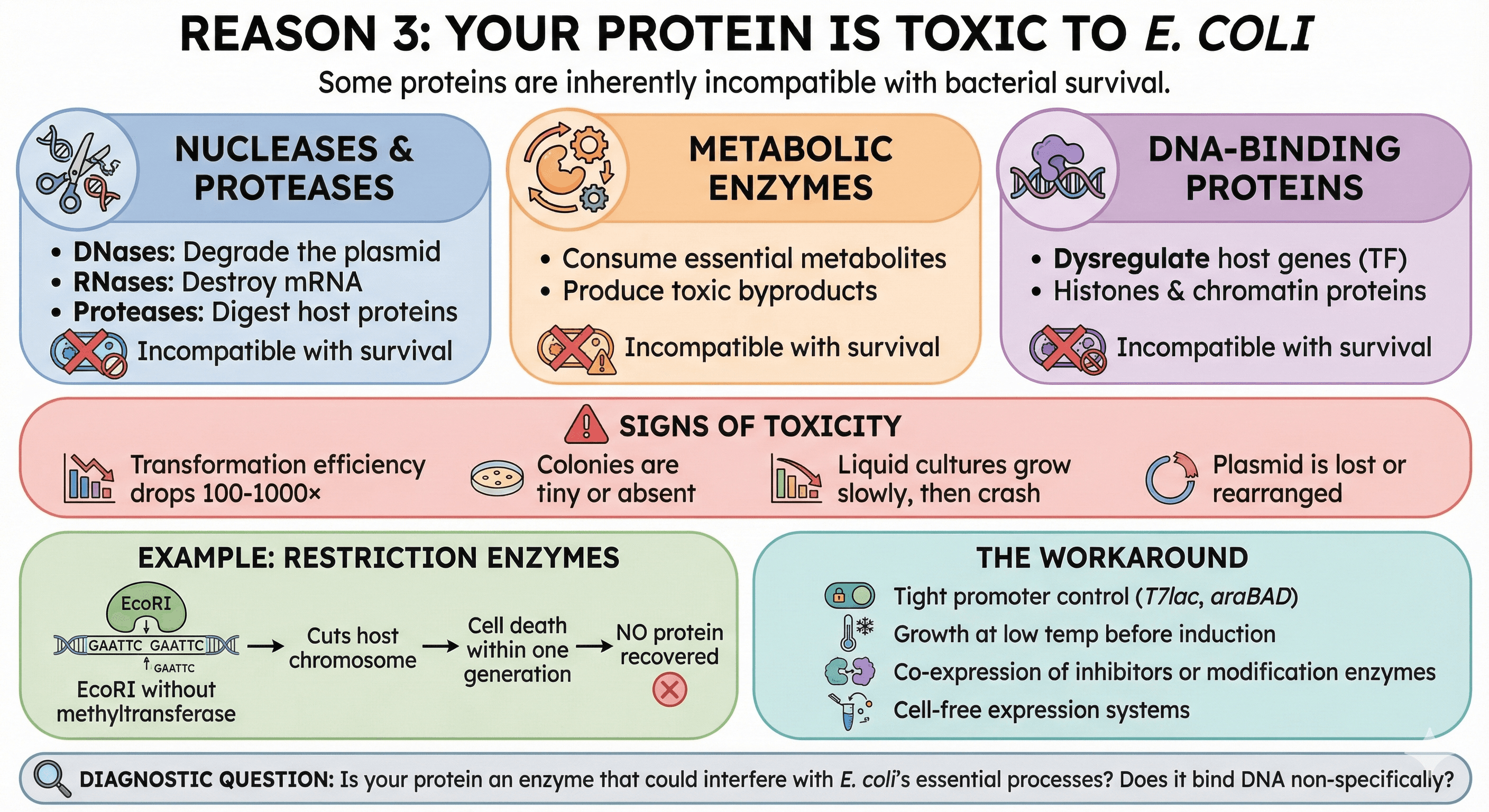

Reason 3: Your Protein Is Toxic to E. coli

Some proteins are inherently incompatible with bacterial survival. This includes:

Nucleases and proteases:

DNases will degrade the plasmid

RNases will destroy mRNA

Proteases will digest host proteins

Metabolic enzymes:

Enzymes that consume essential metabolites

Enzymes that produce toxic byproducts

DNA-binding proteins:

Transcription factors that dysregulate host genes

Histones and chromatin proteins

Signs of toxicity:

Transformation efficiency drops 100-1000×

Colonies are tiny or absent

Liquid cultures grow slowly, then crash

Plasmid is lost or rearranged

Example: Restriction enzymes

EcoRI cuts the recognition sequence GAATTC. E. coli's genome contains hundreds of GAATTC sites. Express EcoRI without its methyltransferase partner, and:

The enzyme cuts the host chromosome

Cell death within one generation

No protein recovered

The workaround:

Tight promoter control (T7lac, araBAD)

Growth at low temperature before induction

Co-expression of inhibitors or modification enzymes

Cell-free expression systems

Diagnostic question: Is your protein an enzyme that could interfere with E. coli's essential processes? Does it bind DNA non-specifically?

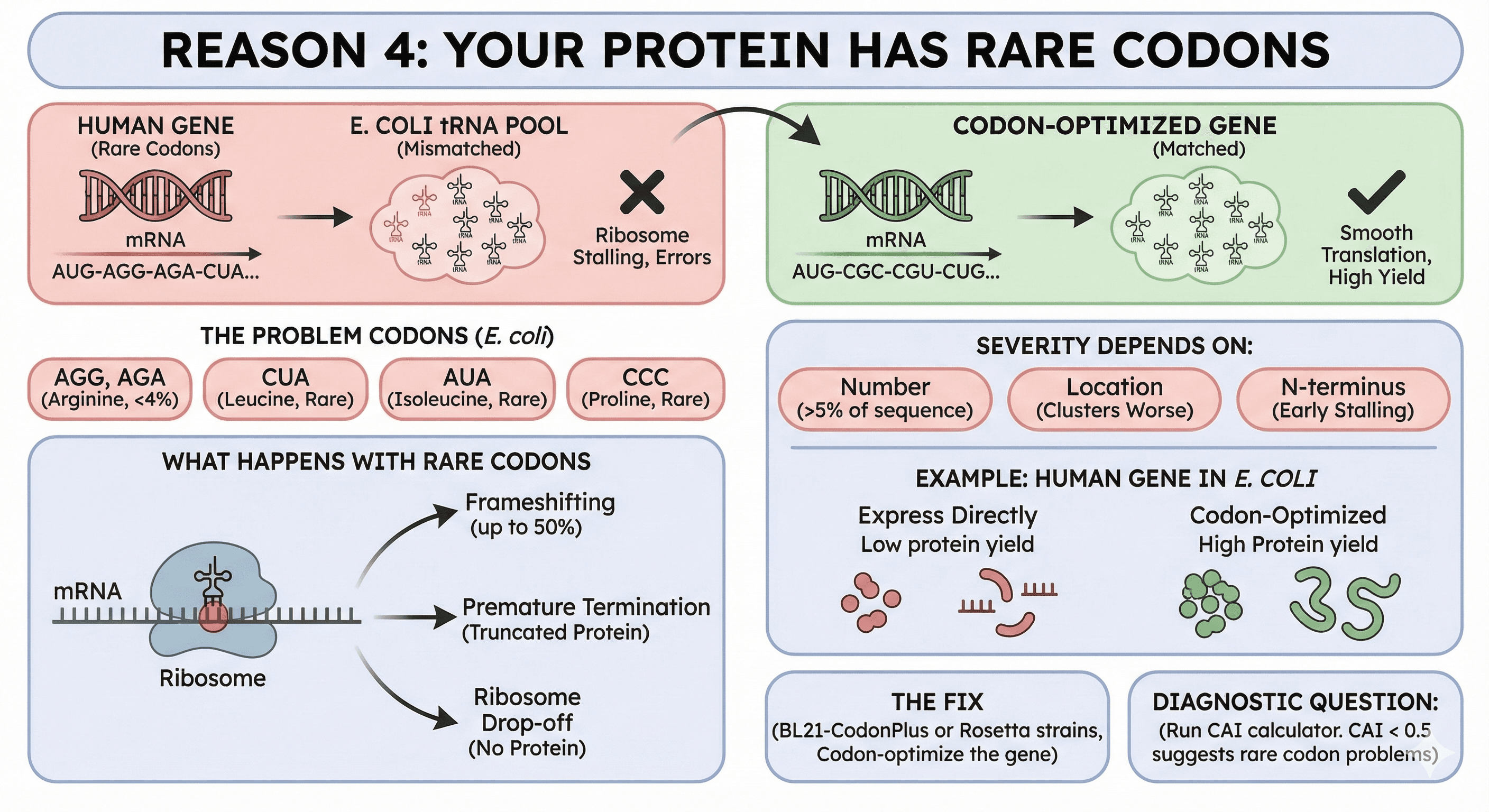

Reason 4: Your Protein Has Rare Codons

E. coli's tRNA pool is optimized for E. coli genes. Human genes use different codon preferences.

The problem codons (Chen & Bhargava, 1994):

AGG, AGA (Arginine): The rarest codons in E. coli, comprising only 2% and 4% of arginine codons respectively

CUA (Leucine): Rare

AUA (Isoleucine): Rare

CCC (Proline): Rare

What happens with rare codons:

Ribosome stalls waiting for the rare tRNA

Stalling causes frameshifting—up to 50% frameshifting at tandem AGG_AGG or AGA_AGA codons (Spanjaard & Van Duin, 1988)

Stalling causes premature termination (truncated protein)

Stalling causes ribosome drop-off (no protein)

The severity depends on:

How many rare codons (>5% of sequence is problematic)

Where they are (clusters are worse than distributed)

Whether they're in the N-terminus (early stalling = no protein)

Example: Human genes in E. coli

A typical human gene might have 10-15% rare codons. Express directly:

Yield drops 10-100× compared to codon-optimized version

Truncation products appear

Full-length protein is often misfolded

The fix:

Use BL21-CodonPlus or Rosetta strains (supply rare tRNAs)

Codon-optimize the gene (change codons, not amino acids)

Both together for difficult cases

Diagnostic question: Run your sequence through a codon adaptation index (CAI) calculator. CAI < 0.5 suggests rare codon problems.

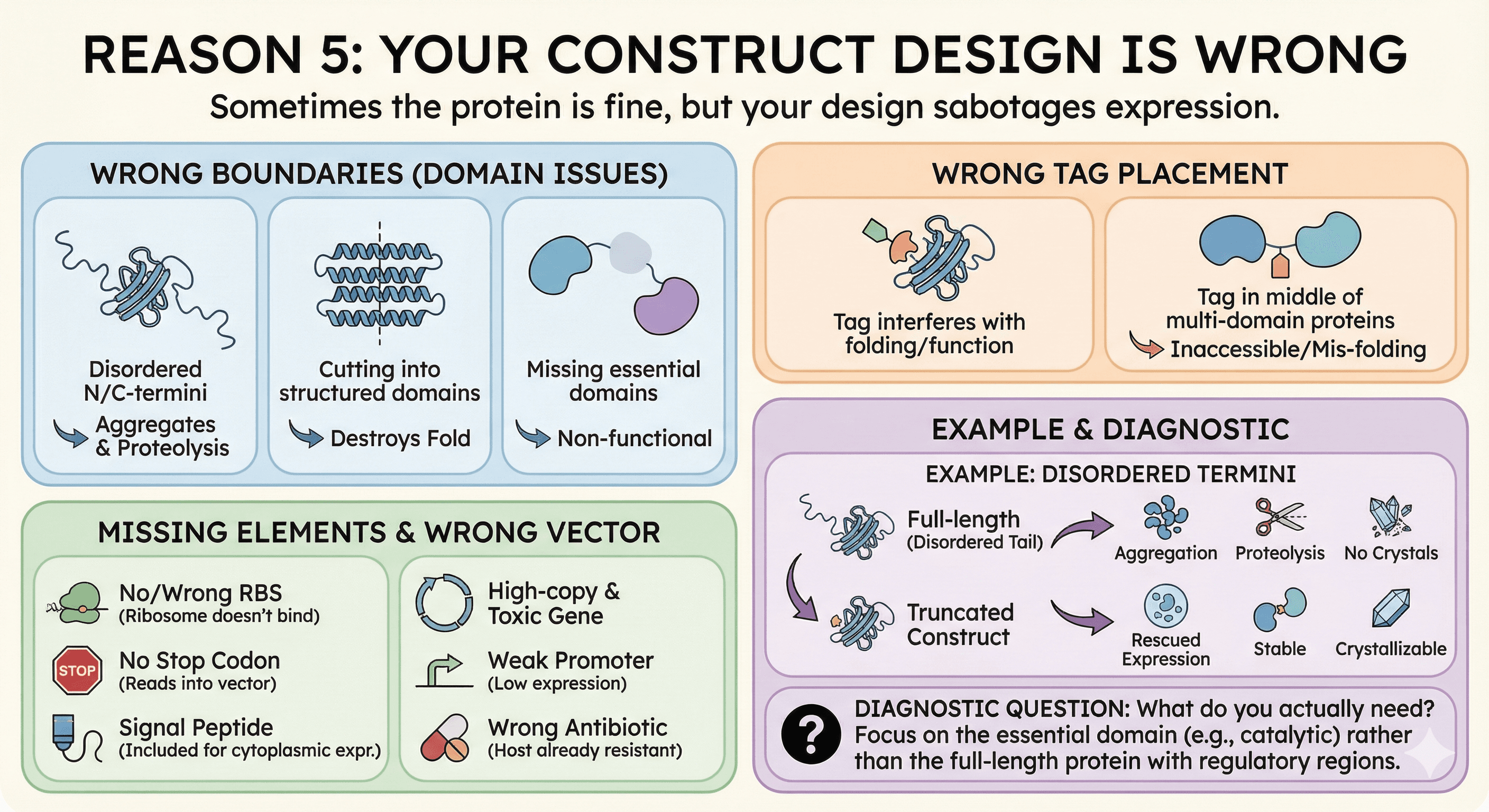

Reason 5: Your Construct Design Is Wrong

Sometimes the protein itself is fine in E. coli, but your construct design sabotages expression.

Common construct problems:

Wrong boundaries:

Including disordered N/C-termini that promote aggregation

Cutting into structured domains (destroys fold)

Missing essential domains (non-functional protein)

Wrong tag placement:

N-terminal tags on proteins that need free N-terminus

Tags that interfere with folding

Tags in the middle of multi-domain proteins

Missing elements:

No ribosome binding site (or wrong spacing)

No stop codon (ribosome reads into vector)

Signal peptide included when cytoplasmic expression intended

Wrong vector:

High-copy plasmid with toxic gene (see Reason 3)

Weak promoter for high-expression needs

Wrong antibiotic resistance (already in host)

Example: Disordered termini

Many proteins have flexible N- or C-terminal tails that are disordered. In the cell, these might be functional (protein-protein interactions, localization). In a test tube:

They promote aggregation

They get cleaved by proteases

They make crystallization impossible

Truncating these regions often rescues expression.

Diagnostic question: What do you actually need? If you want the catalytic domain, express the catalytic domain—not the full-length protein with regulatory regions.

The Decision Tree: Before You Clone

The cheapest experiment is the one you don't run. Before committing to E. coli, run this decision tree:

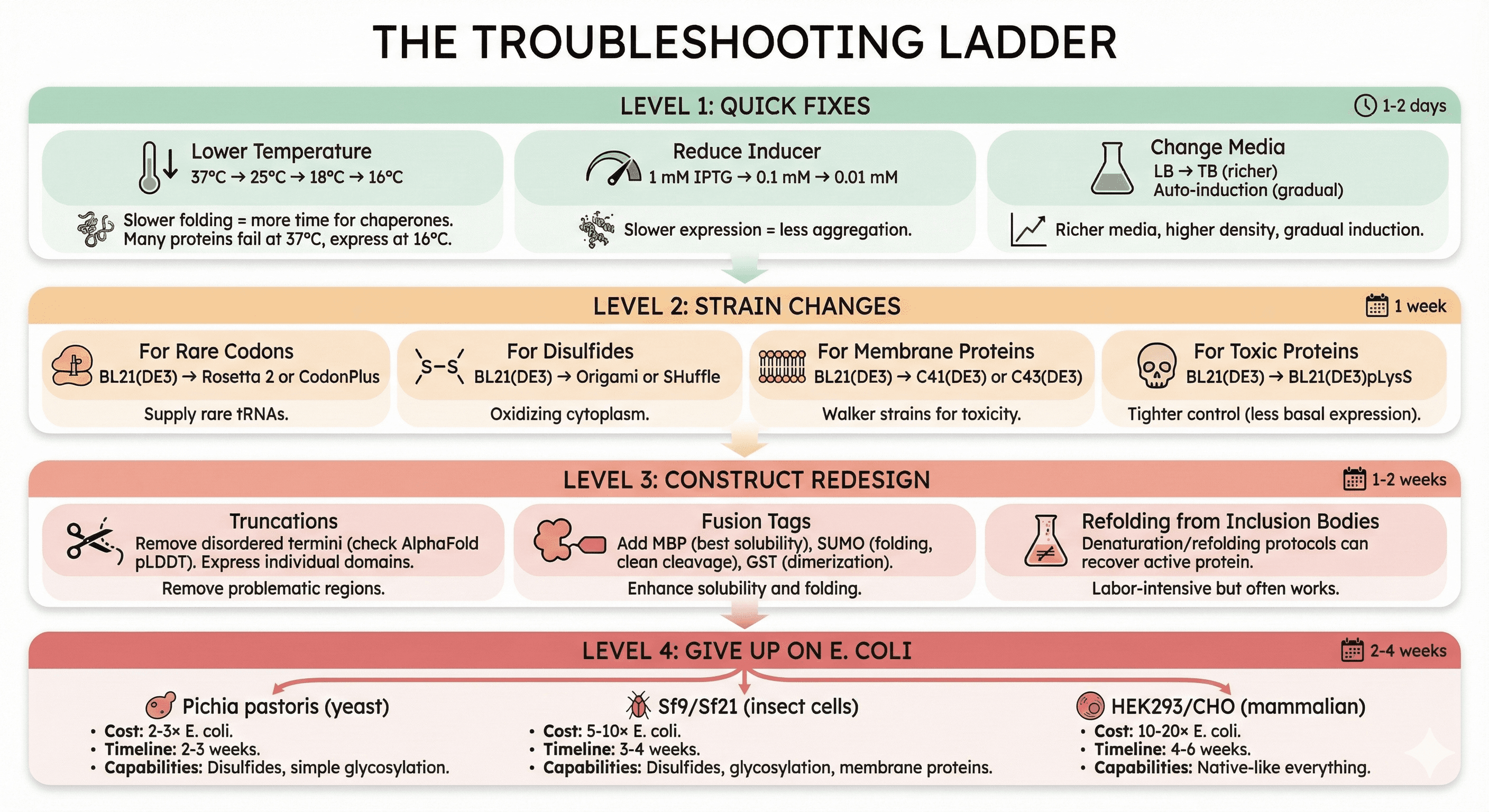

The Troubleshooting Ladder

If you've already tried E. coli and failed, work through this systematically:

Level 1: Quick Fixes (1-2 days)

Lower temperature:

37°C → 25°C → 18°C → 16°C

Slower folding = more time for chaperones

Many proteins that fail at 37°C express at 16°C

Reduce inducer:

1 mM IPTG → 0.1 mM → 0.01 mM

Slower expression = less aggregation

Change media:

LB → TB (richer, higher density)

Auto-induction media (gradual induction)

Level 2: Strain Changes (1 week)

For rare codons:

BL21(DE3) → Rosetta 2 or CodonPlus

For disulfides:

BL21(DE3) → Origami or SHuffle

For membrane proteins:

BL21(DE3) → C41(DE3) or C43(DE3) (Walker strains)

For toxic proteins:

BL21(DE3) → BL21(DE3)pLysS (tighter control)

Level 3: Construct Redesign (1-2 weeks)

Truncations:

Remove disordered termini (check AlphaFold pLDDT)

Express individual domains

Fusion tags:

Add MBP (maltose binding protein) - best for solubility

Add SUMO - improves folding, clean cleavage

Add GST - dimerization can help some proteins

Refolding from inclusion bodies:

Sometimes the protein expresses abundantly but insoluble

Denaturation/refolding protocols can recover active protein

Labor-intensive but often works

Level 4: Give Up on E. coli (2-4 weeks)

If levels 1-3 fail, the protein genuinely needs a eukaryotic system:

Pichia pastoris (yeast):

Cost: 2-3× E. coli

Timeline: 2-3 weeks

Capabilities: Disulfides, simple glycosylation

Sf9/Sf21 (insect cells):

Cost: 5-10× E. coli

Timeline: 3-4 weeks

Capabilities: Disulfides, glycosylation, membrane proteins

HEK293/CHO (mammalian):

Cost: 10-20× E. coli

Timeline: 4-6 weeks

Capabilities: Native-like everything

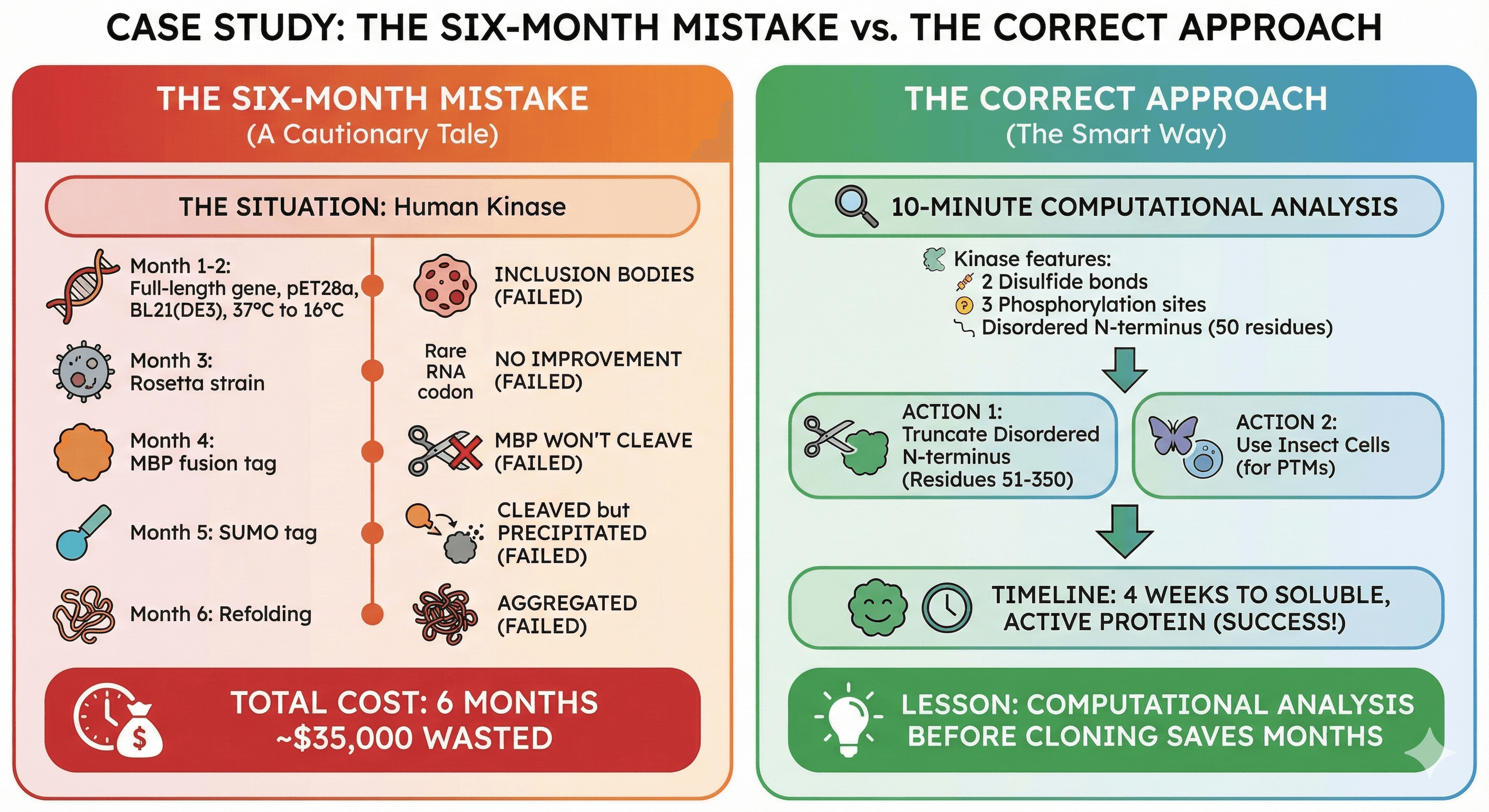

Case Study: The Six-Month Mistake

The Situation

A structural biology lab wanted to crystallize a human kinase. The postdoc:

Cloned full-length gene into pET28a (His-tag)

Expressed in BL21(DE3) at 37°C

Got inclusion bodies

The Six-Month Journey

Months 1-2: Tried every temperature (37°C, 25°C, 18°C, 16°C). Still inclusion bodies.

Month 3: Tried Rosetta strain for rare codons. No improvement.

Month 4: Added MBP fusion tag. Now soluble! But MBP wouldn't cleave off.

Month 5: Tried SUMO tag. Cleaved cleanly. But protein precipitated immediately after cleavage.

Month 6: Tried refolding from inclusion bodies. Got some soluble protein. It was aggregated.

Total cost: 6 months of postdoc time (~$30k), reagents (~$5k), opportunity cost (priceless).

What Should Have Happened

Before cloning, a 10-minute analysis would have revealed:

The kinase has 4 cysteines that form 2 disulfide bonds

It has 3 phosphorylation sites essential for activity

The N-terminal 50 residues are disordered and aggregation-prone

The correct approach:

Truncate disordered N-terminus (residues 51-350)

Use insect cells (disulfides + phosphorylation)

Timeline: 4 weeks to soluble, active protein

Lesson: Computational analysis before cloning saves months.

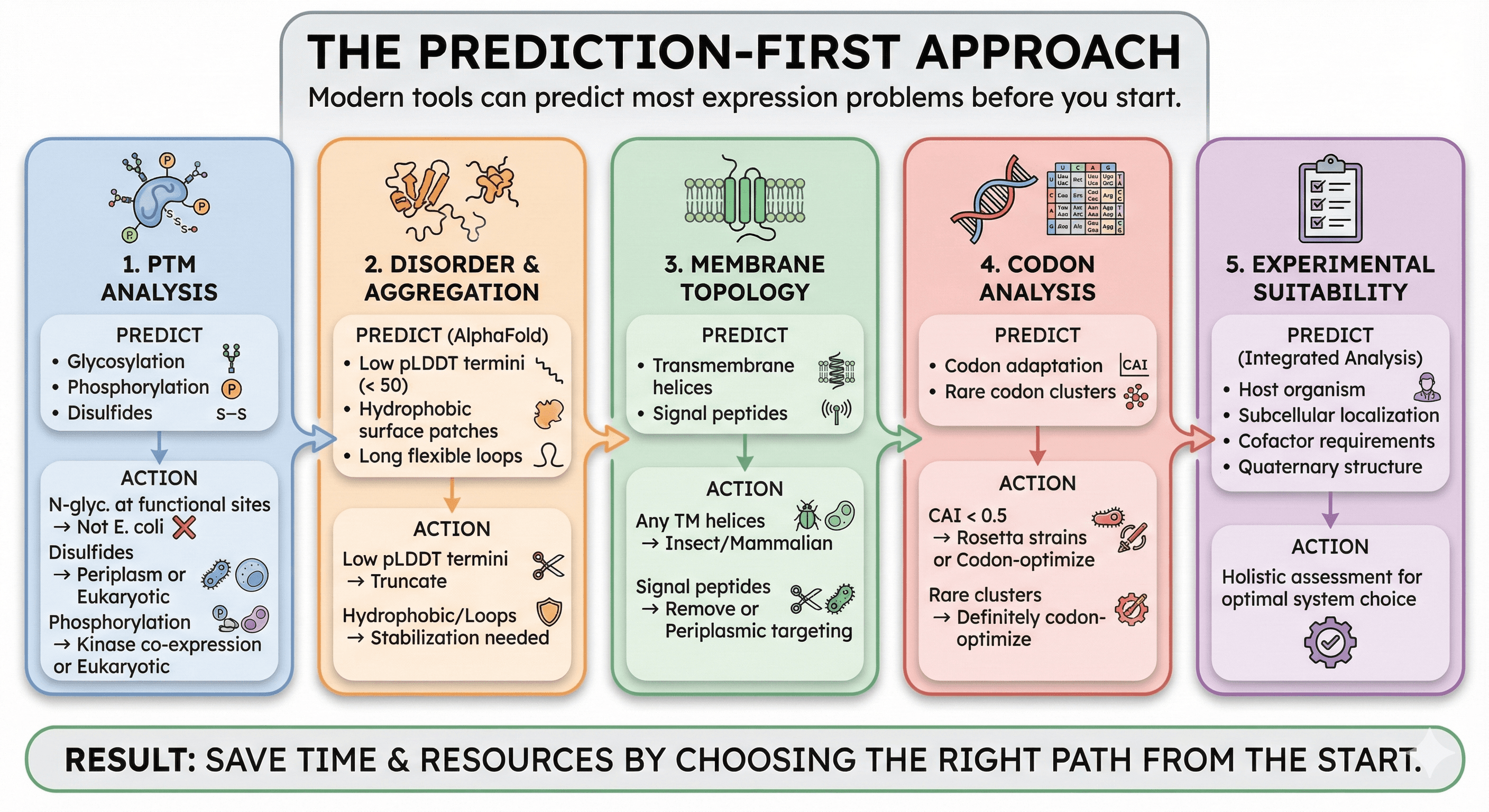

The Prediction-First Approach

Modern tools can predict most expression problems before you start:

1. PTM Analysis

Predict glycosylation, phosphorylation, and other modifications:

If N-glycosylation is predicted at functional sites → not E. coli

If disulfides are predicted → consider periplasm or eukaryotic

If phosphorylation is required for activity → need kinase co-expression or eukaryotic

2. Disorder and Aggregation

Check AlphaFold structure for:

Low pLDDT regions (< 50) at termini → candidate for truncation

Hydrophobic patches on surface → aggregation risk

Long flexible loops → may need stabilization

3. Membrane Topology

Predict transmembrane helices:

Any TM helices → consider insect/mammalian

Signal peptides → may need removal or periplasmic targeting

4. Codon Analysis

Check codon adaptation:

CAI < 0.5 → use Rosetta strains or codon-optimize

Clusters of rare codons → definitely codon-optimize

5. Experimental Suitability

Integrated analysis that considers:

Host organism association

Subcellular localization

Cofactor requirements

Quaternary structure

The Bottom Line

E. coli expression failure isn't random bad luck. It's a predictable consequence of mismatched requirements:

Your Protein Needs | E. coli Provides | Result |

|---|---|---|

Glycosylation | Nothing | Misfolding |

Disulfide bonds | Reducing cytoplasm | Aggregation |

Membrane insertion | Bacterial translocon | Inclusion bodies |

Rare tRNAs | Standard tRNA pool | Truncation |

Complex folding | Fast translation | Misfolding |

The old approach: Clone → Express → Fail → Troubleshoot for months

The new approach: Analyze → Predict requirements → Choose system → Express → Succeed

The difference between a "difficult protein" and a "successful expression" is often just choosing the right system before you start—not after six months of failure.

Matching Your Protein to the Right System

For researchers dealing with expression failures, platforms like Orbion can predict PTM requirements, aggregation hotspots, and expression system compatibility before you clone. The analysis takes minutes; the troubleshooting it prevents takes months.

What Orbion provides:

PTM prediction (glycosylation, phosphorylation, disulfides)

Experimental suitability assessment (host organism, subcellular location, cofactors)

Aggregation propensity mapping

Expression system recommendations based on your protein's specific requirements

The goal isn't to avoid E. coli—it's the best system when it works. The goal is to know when it won't work, before you waste months discovering that the hard way.

References

Braun P, et al. (2005). Structural genomics of human proteins – target selection and generation of a public catalogue of expression clones. Microbial Cell Factories, 4:21. PMC1250228

Apweiler R, et al. (1999). On the frequency of protein glycosylation, as deduced from analysis of the SWISS-PROT database. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1473(1):4-8.

Wang W, et al. (2017). Glycosylation engineering of therapeutic IgG antibodies: challenges for the safety, functionality and efficacy. Protein & Cell, 9(1):16-25. Link

Baeshen MN, et al. (2021). Downstream processing of recombinant human insulin and its analogues production from E. coli inclusion bodies. Bioresources and Bioprocessing, 8:78. PMC8313369

Bill RM, et al. (2011). High-throughput expression and purification of membrane proteins. Journal of Structural Biology, 172(1):73-82. PMC2933282

Lv X, et al. (2016). Expression and purification of recombinant G protein-coupled receptors: A review. Protein Expression and Purification, 123:1-6. PMC6983937

Chen GT & Bhargava MM. (1994). Role of the AGA/AGG codons, the rarest codons in global gene expression in Escherichia coli. Genes & Development, 8(21):2641-52. Link

Spanjaard RA & Van Duin J. (2005). Expression levels influence ribosomal frameshifting at the tandem rare arginine codons AGG_AGG and AGA_AGA in Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology, 187(12):4023-4032. PMC1151738