Blog

Why Your Protein Won't Crystallize: Understanding the 6 Common Failure Modes

Dec 29, 2025

You've spent 6 months expressing and purifying your protein. The SEC-MALS looks perfect—monodisperse, no aggregates. Thermal stability is excellent. You set up 96-well crystallization screens. Two weeks later: clear drops. No crystals.

You try another screen. Then another. Different concentrations. Different buffers. Six months pass. Still nothing.

Welcome to the most frustrating bottleneck in structural biology: crystallization. It kills more structural projects than any other technical barrier, and the failure mechanisms are often invisible until you know exactly what to look for.

This is Part 1 of our crystallization troubleshooting guide. Here, we'll diagnose why proteins fail to crystallize. In Part 2, we'll cover how to fix each problem with modern computational tools.

Key Takeaways

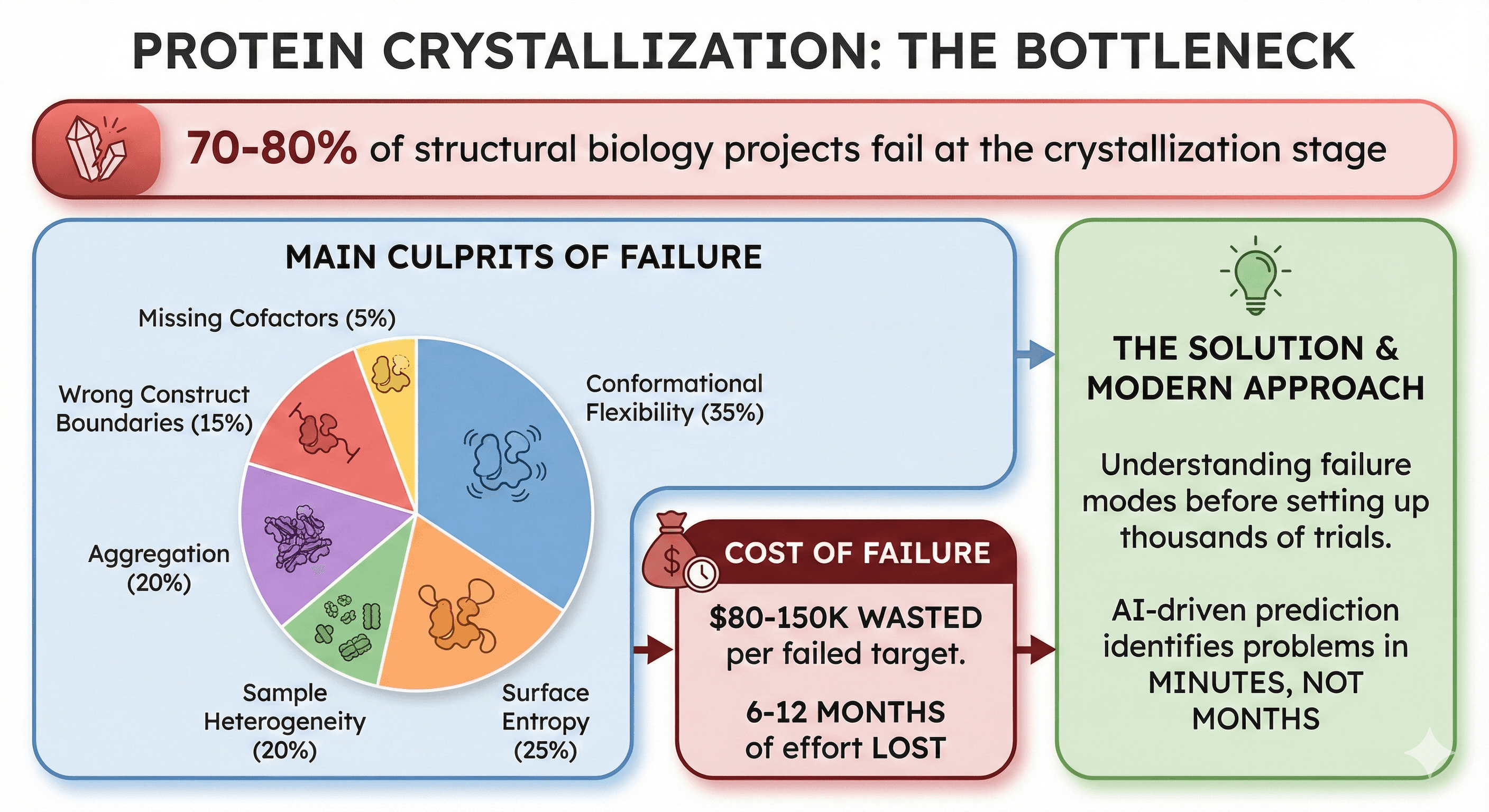

70-80% of structural biology projects fail at the crystallization stage

Main culprits: Conformational flexibility (35%), surface entropy (25%), sample heterogeneity (20%), wrong construct boundaries (15%), aggregation (20%), missing cofactors (5%)

Cost of failure: $80-150K wasted per failed target (6-12 months of effort)

The solution: Understanding failure modes before setting up thousands of crystallization trials

Modern approach: AI-driven prediction identifies problems in minutes, not months

The Crystallization Crisis: By the Numbers

The Economic Reality

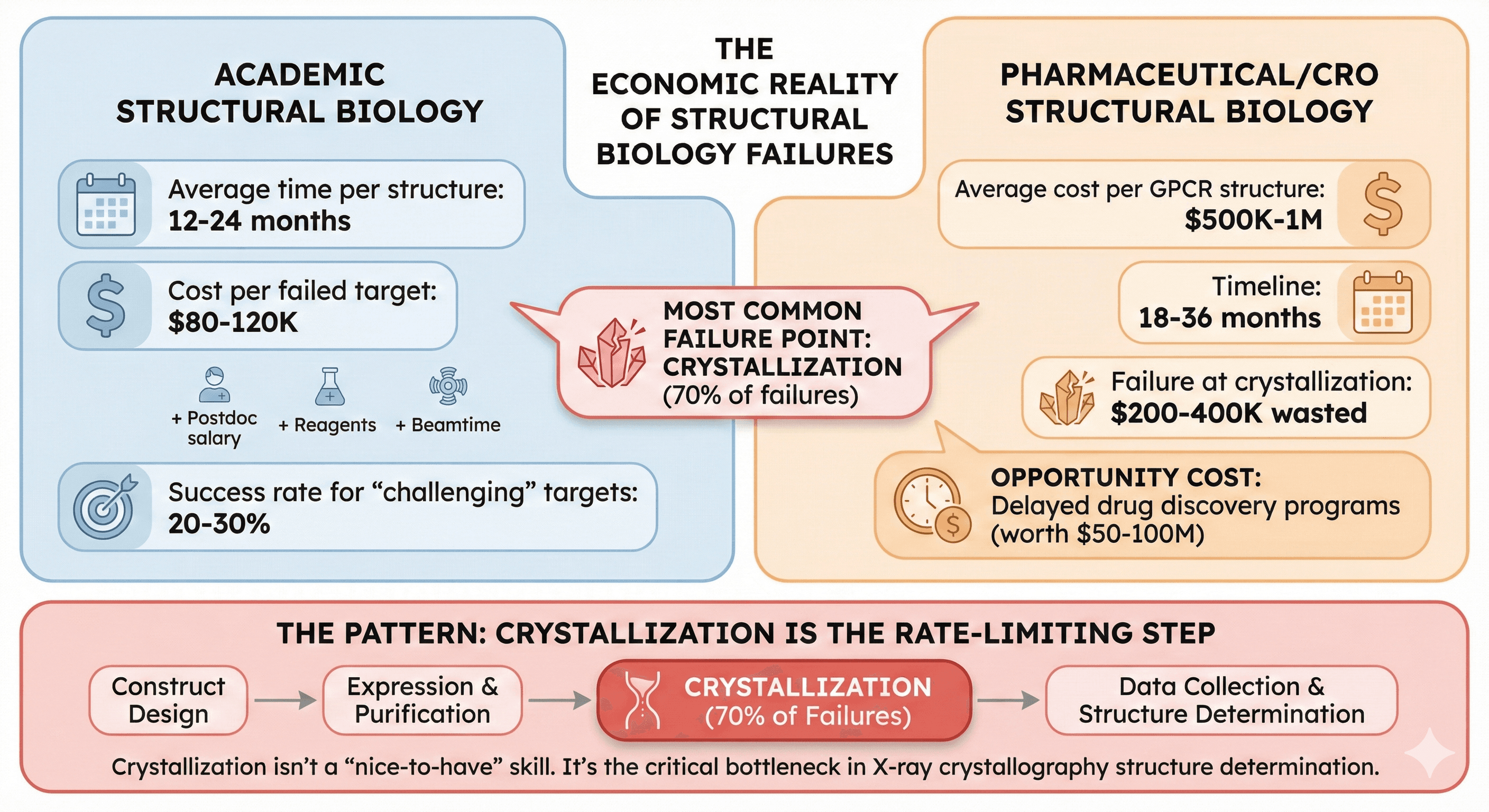

Academic structural biology:

Average time per structure: 12-24 months

Cost per failed target: $80-120K (postdoc salary + reagents + beamtime)

Success rate for "challenging" targets: 20-30%

Most common failure point: Crystallization (70% of failures)

Pharmaceutical/CRO structural biology:

Average cost per GPCR structure: $500K-1M

Timeline: 18-36 months

Failure at crystallization: $200-400K wasted

Opportunity cost: Delayed drug discovery programs (worth $50-100M)

The pattern: Crystallization isn't a "nice-to-have" skill. It's the rate-limiting step in structure determination for X-ray crystallography.

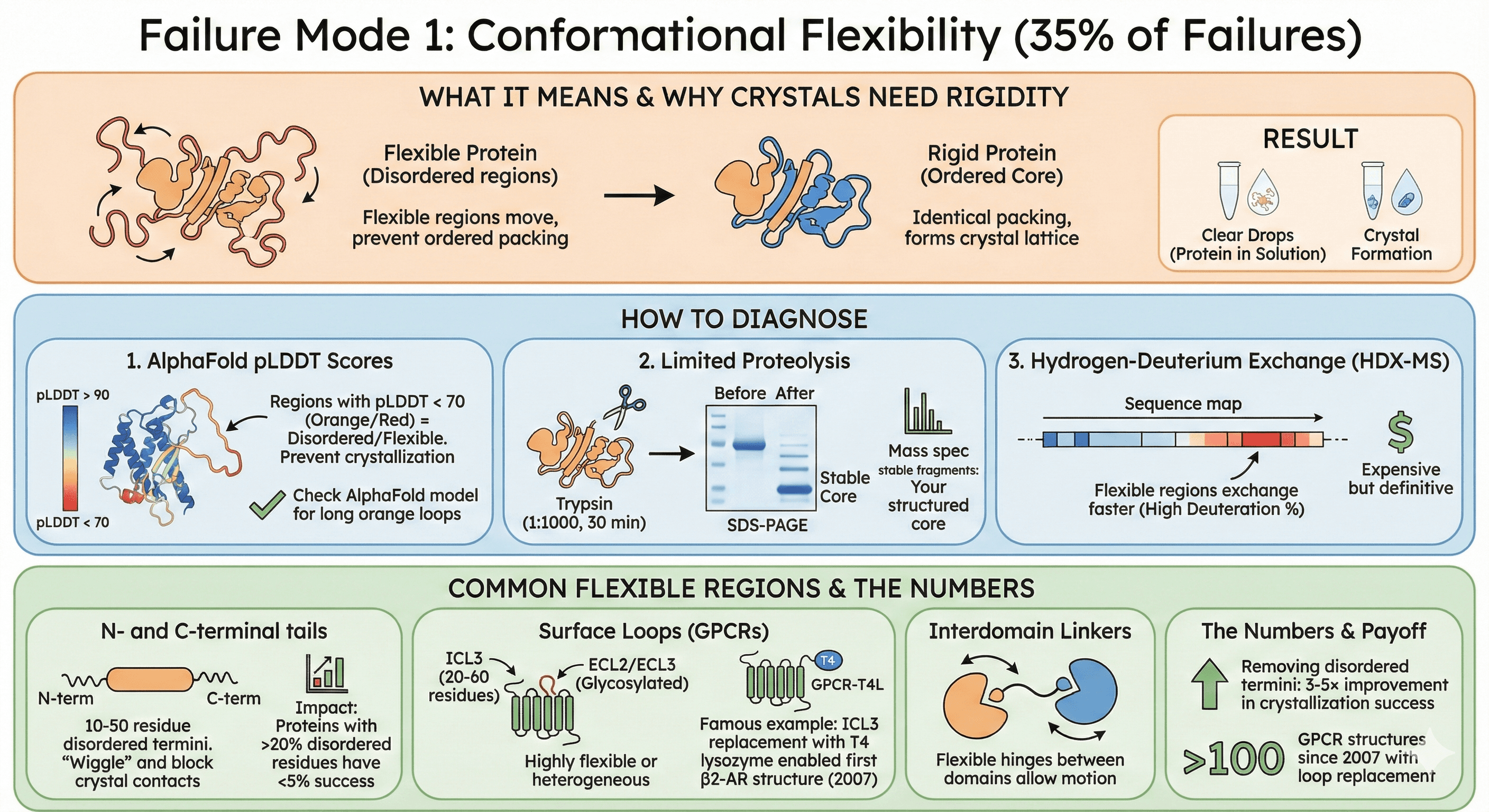

Failure Mode 1: Conformational Flexibility (35% of Failures)

What it means: Your protein has flexible regions (loops, termini, linkers) that move and prevent the tight, ordered packing required for crystal lattice formation.

Why crystals need rigidity:

Crystallization requires identical packing of every protein molecule

Flexible regions adopt different conformations in each molecule

No single, repeatable lattice can form

Result: Protein stays in solution (clear drops)

How to Diagnose

1. AlphaFold pLDDT scores:

Regions with pLDDT < 70 (orange/red) = disordered/flexible

These regions will prevent crystallization

Check your AlphaFold model: Are there long orange loops?

2. Limited proteolysis:

Treat purified protein with low protease (trypsin 1:1000, 30 min)

Run SDS-PAGE: Flexible loops are cleaved first

Mass spec the stable fragments: These are your structured core

3. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX-MS):

Flexible regions exchange faster (high deuteration %)

Expensive but definitive

Identifies exact residues that are flexible

Common Flexible Regions

N- and C-terminal tails:

Most proteins have 10-50 residue disordered termini

These "wiggle" in solution, blocking crystal contacts

Impact: Proteins with >20% disordered residues have <5% crystallization success

Surface loops (especially in GPCRs):

Intracellular loop 3 (ICL3) in GPCRs: 20-60 residues, highly flexible

Extracellular loops (ECL2, ECL3): Glycosylated, heterogeneous

Famous example: GPCR ICL3 replacement with T4 lysozyme enabled first β2-AR structure (2007)

Interdomain linkers:

Flexible hinges between domains

Allow domain motion (biologically important, structurally problematic)

The numbers:

Removing disordered termini: 3-5× improvement in crystallization success

GPCR loop replacement: Enabled >100 GPCR structures since 2007

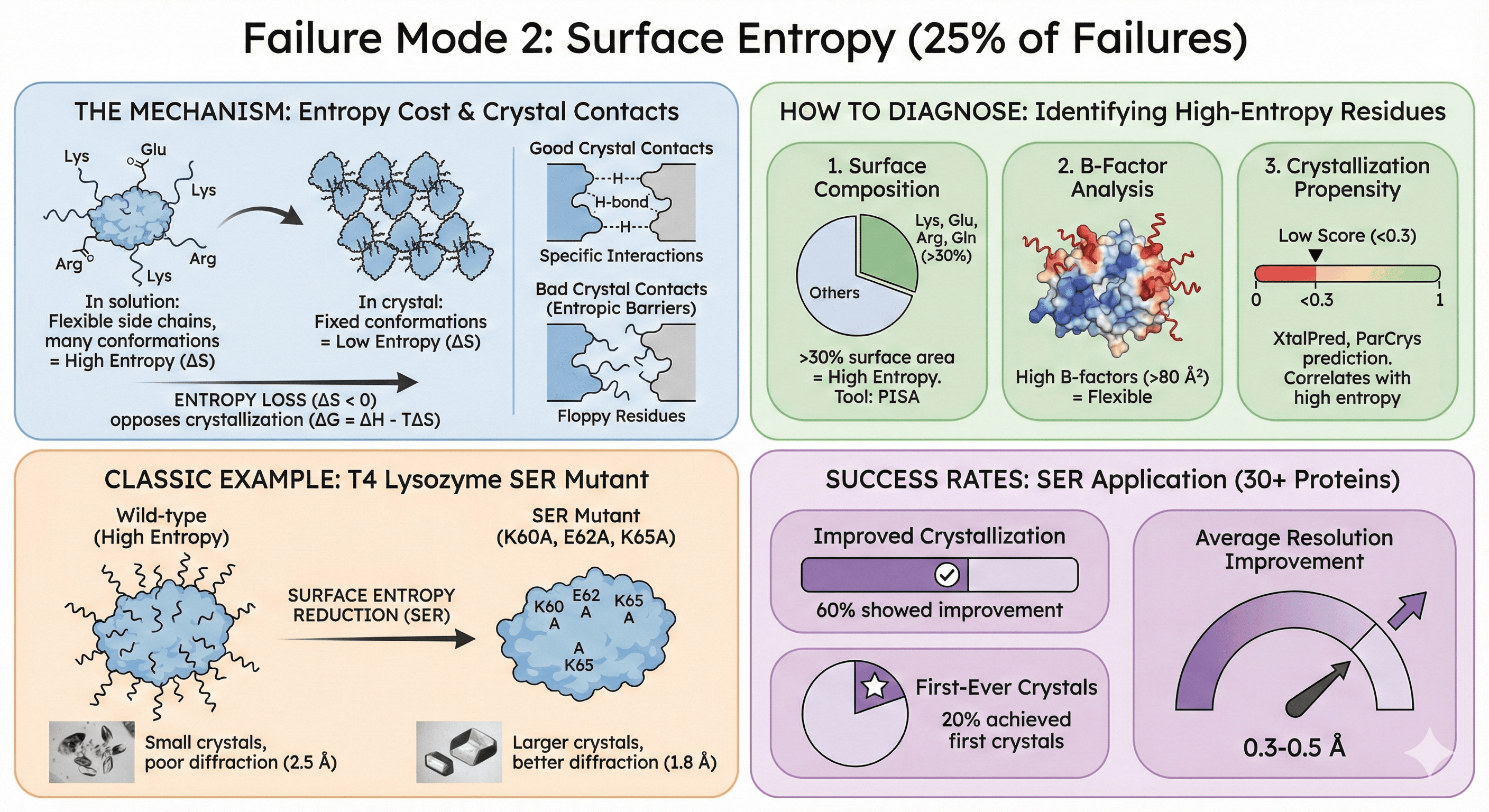

Failure Mode 2: Surface Entropy (25% of Failures)

What it means: High-entropy surface residues (long, flexible side chains like Lys, Glu, Arg) prevent tight crystal packing.

The Mechanism

Entropy cost of crystallization:

In solution: Lys, Glu, Arg side chains are flexible (many conformations = high entropy)

In crystal: These side chains must adopt fixed conformations (low entropy)

Entropy loss opposes crystallization (ΔG = ΔH - TΔS; large negative ΔS makes ΔG unfavorable)

Crystal contacts require specificity:

Good crystal contacts: Complementary surfaces with specific interactions (H-bonds, salt bridges)

Bad crystal contacts: Floppy residues that can't form stable interfaces

High-entropy residues create "entropic barriers" to crystallization

How to Diagnose

1. Surface composition analysis:

Calculate % of surface area occupied by Lys, Glu, Arg, Gln

>30% = high entropy, poor crystallization propensity

Tool: PISA (protein surface analysis)

2. B-factor analysis (if you have homolog structures):

High B-factors (>80 Ų) on surface residues = flexible

These residues will resist crystallization

3. Crystallization propensity prediction:

XtalPred, ParCrys: Predict crystallization likelihood from sequence

Low scores (<0.3) often correlate with high surface entropy

Classic Example: T4 Lysozyme

Wild-type: Difficult to crystallize (small crystals, poor diffraction) SER mutant: K60A, E62A, K65A (three surface mutations) Result: Larger crystals, better diffraction (2.5 Å → 1.8 Å resolution)

Success rates:

SER applied to 30+ proteins: 60% showed improved crystallization

20% achieved first-ever crystals

Average resolution improvement: 0.3-0.5 Å

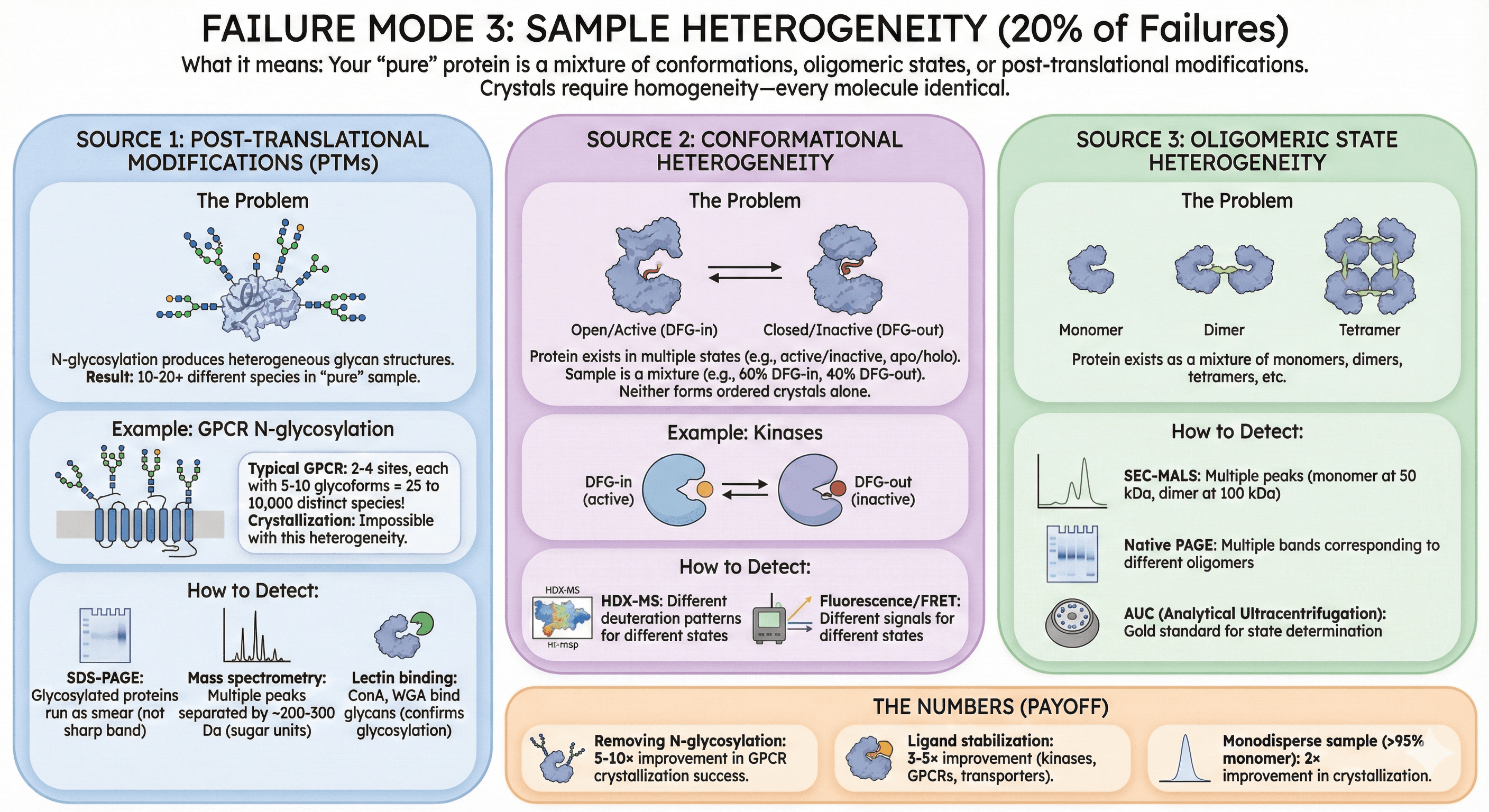

Failure Mode 3: Sample Heterogeneity (20% of Failures)

What it means: Your "pure" protein is actually a mixture of conformations, oligomeric states, or post-translational modifications. Crystals require homogeneity—every molecule identical.

Source 1: Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs)

The problem:

N-glycosylation: Produces heterogeneous glycan structures (different sizes, branching)

Each glycoform behaves differently in crystallization

Result: 10-20 different species in "pure" sample

Example: GPCR N-glycosylation

Typical GPCR has 2-4 N-glycosylation sites

Each site can have 5-10 different glycan structures

Total glycoforms: 5² to 10⁴ = 25 to 10,000 distinct species

Crystallization: Impossible with this heterogeneity

How to detect:

SDS-PAGE: Glycosylated proteins run as smear (not sharp band)

Mass spectrometry: Multiple peaks separated by ~200-300 Da (sugar units)

Lectin binding: ConA, WGA bind glycans (confirms glycosylation)

Source 2: Conformational Heterogeneity

The problem: Protein exists in multiple conformational states (open/closed, active/inactive, apo/holo).

Example: Kinases

DFG-in (active) vs DFG-out (inactive)

Your sample is a mixture (60% DFG-in, 40% DFG-out)

Neither conformation can form ordered crystals alone

Source 3: Oligomeric State Heterogeneity

The problem: Protein exists as mixture of monomers, dimers, tetramers.

How to detect:

SEC-MALS: Multiple peaks (monomer at 50 kDa, dimer at 100 kDa)

Native PAGE: Multiple bands

AUC (analytical ultracentrifugation): Gold standard

The numbers:

Removing N-glycosylation: 5-10× improvement in GPCR crystallization success

Ligand stabilization: 3-5× improvement (kinases, GPCRs, transporters)

Monodisperse sample (>95% monomer): 2× improvement in crystallization

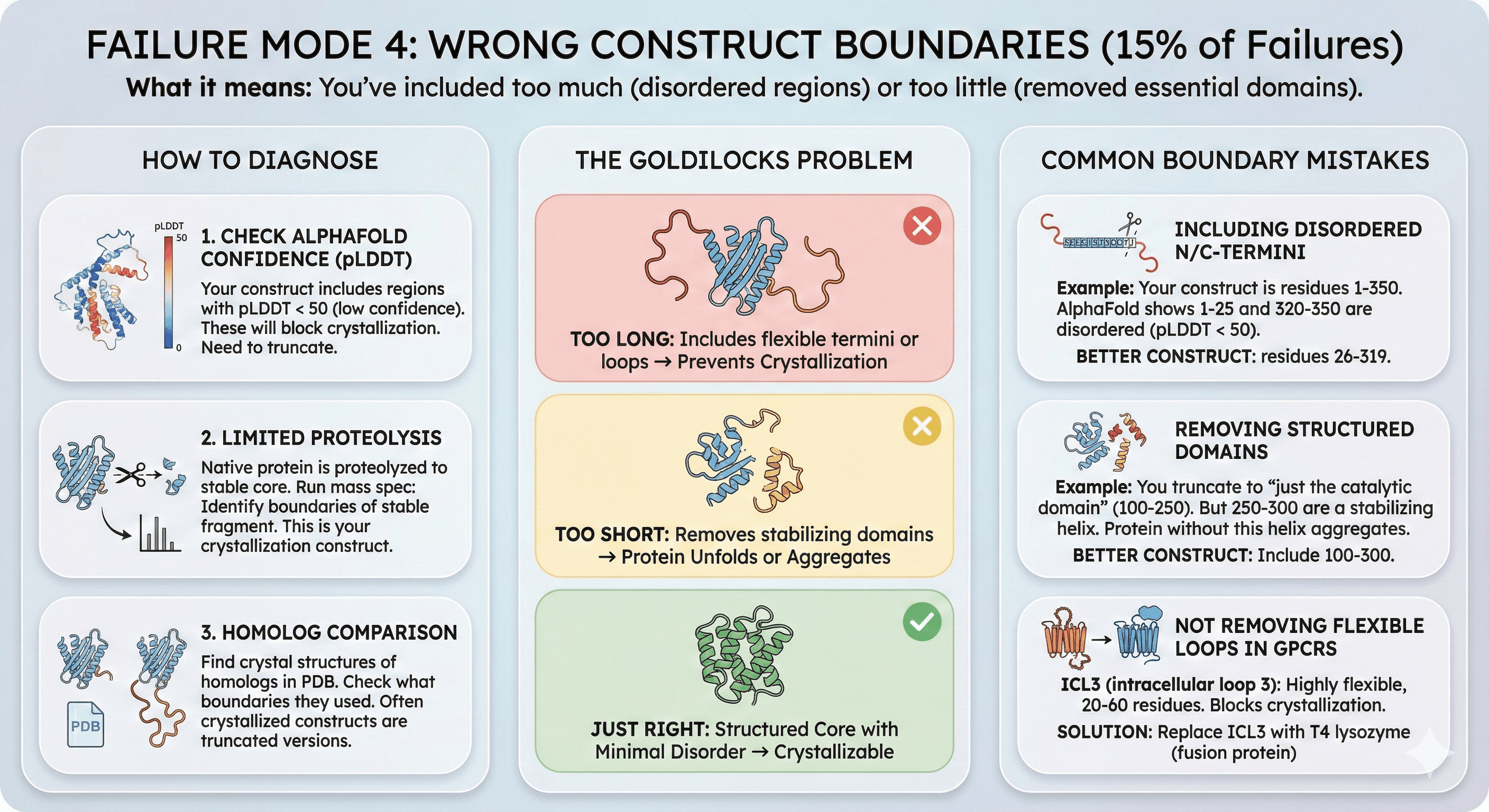

Failure Mode 4: Wrong Construct Boundaries (15% of Failures)

What it means: You've included too much (disordered regions that prevent packing) or too little (removed essential domains).

The Goldilocks Problem

Too long: Includes flexible termini or loops → prevents crystallization Too short: Removes stabilizing domains → protein unfolds or aggregates Just right: Structured core with minimal disorder

How to Diagnose

1. Check AlphaFold confidence (pLDDT):

Your construct includes regions with pLDDT < 50 (low confidence)

These disordered regions will block crystallization

Need to truncate

2. Limited proteolysis:

Native protein is proteolyzed to stable core

Run mass spec: Identify boundaries of stable fragment

This is your crystallization construct

3. Homolog comparison:

Find crystal structures of homologs in PDB

Check what boundaries they used

Often crystallized constructs are truncated versions

Common Boundary Mistakes

Including disordered N/C-termini:

Example: Your construct is residues 1-350

AlphaFold shows residues 1-25 and 320-350 are disordered (pLDDT < 50)

Better construct: residues 26-319

Removing structured domains:

Example: You truncate to "just the catalytic domain" (residues 100-250)

But residues 250-300 are a stabilizing helix

Protein without this helix aggregates

Better construct: Include 100-300

Not removing flexible loops in GPCRs:

ICL3 (intracellular loop 3): Highly flexible, 20-60 residues

Blocks crystallization (prevents ordered packing)

Solution: Replace ICL3 with T4 lysozyme (fusion protein)

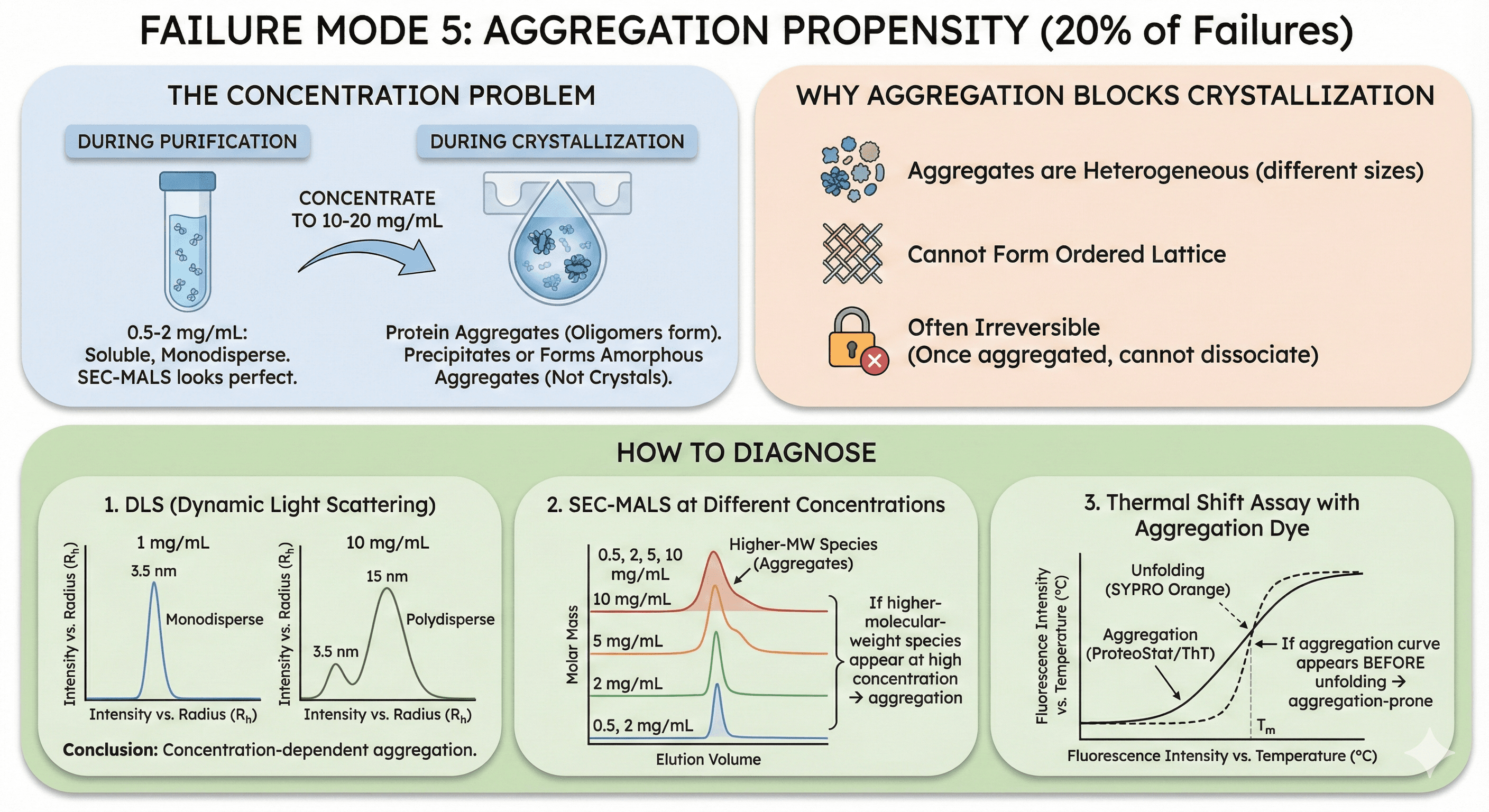

Failure Mode 5: Aggregation Propensity (20% of Failures)

What it means: Your protein has surface-exposed hydrophobic patches that cause aggregation at crystallization concentrations (5-20 mg/mL).

The Concentration Problem

During purification:

Protein at 0.5-2 mg/mL: Soluble, monodisperse

SEC-MALS looks perfect

During crystallization:

Concentrate to 10-20 mg/mL

Protein aggregates (oligomers form)

Aggregates precipitate or form amorphous aggregates (not crystals)

Why aggregation blocks crystallization:

Aggregates are heterogeneous (different sizes)

Cannot form ordered lattice

Often irreversible (once aggregated, cannot dissociate)

How to Diagnose

1. DLS (Dynamic Light Scattering):

At 1 mg/mL: Monodisperse (Rh = 3.5 nm, single peak)

At 10 mg/mL: Polydisperse (two peaks: 3.5 nm and 15 nm)

Conclusion: Concentration-dependent aggregation

2. SEC-MALS at different concentrations:

Run at 0.5, 2, 5, 10 mg/mL

If higher-molecular-weight species appear at high concentration → aggregation

3. Thermal shift assay with aggregation dye:

SYPRO Orange (standard) detects unfolding

Aggregation dyes (ProteoStat, ThT) detect aggregates

If aggregation curve appears before unfolding → aggregation-prone

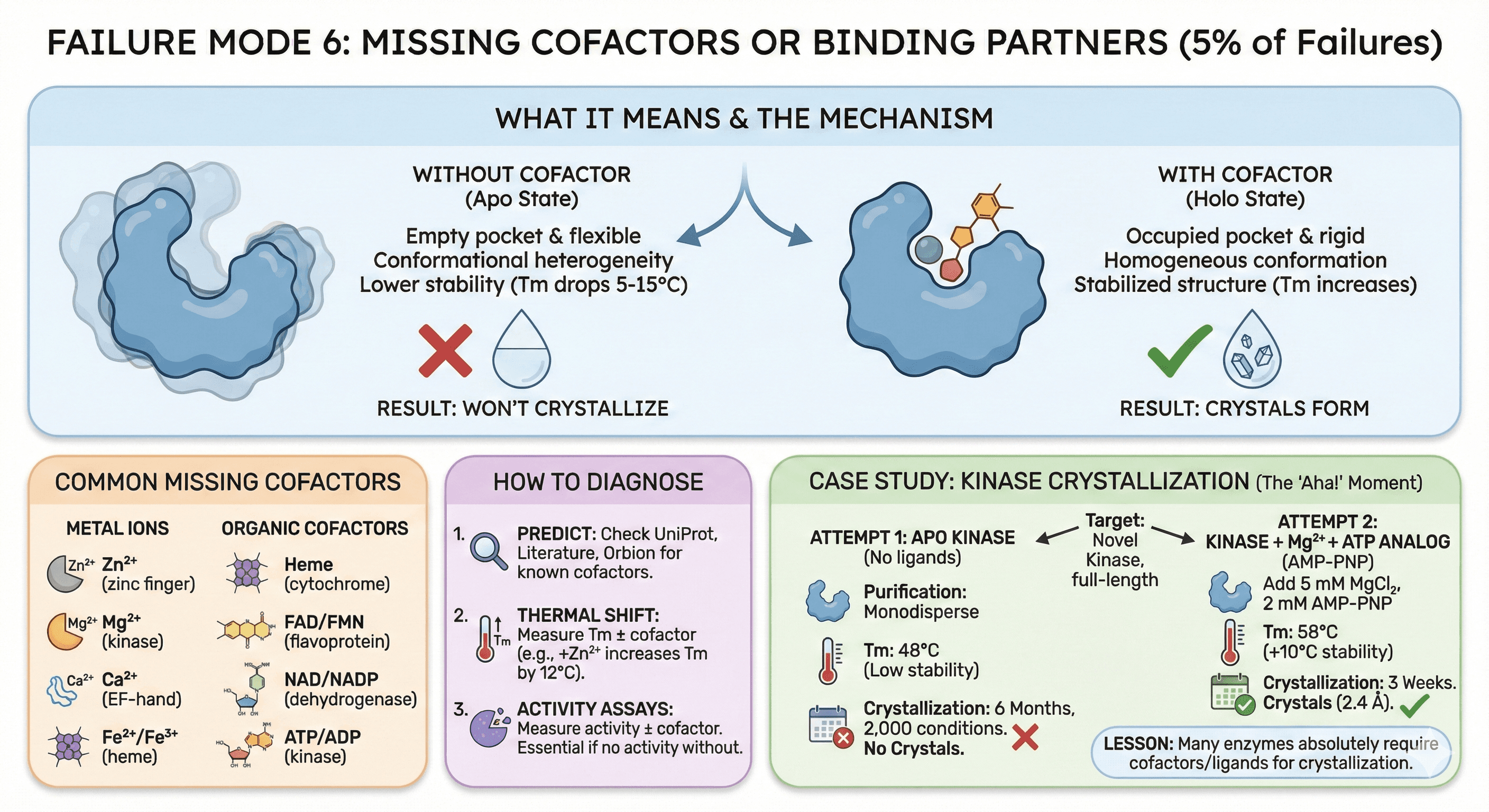

Failure Mode 6: Missing Cofactors or Binding Partners (5% of Failures)

What it means: Your protein requires a cofactor (metal ion, heme, nucleotide) or binding partner to fold correctly or stabilize. Without it, the protein is unstable or heterogeneous.

Common Missing Cofactors

Metal ions:

Zinc (Zn²⁺): Zinc finger domains, metalloproteases

Magnesium (Mg²⁺): Kinases, phosphatases, nucleic acid-binding proteins

Calcium (Ca²⁺): EF-hand domains, some proteases

Iron (Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺): Heme proteins, iron-sulfur clusters

Organic cofactors:

Heme: Cytochromes, peroxidases, hemoglobin

FAD/FMN: Flavoproteins, oxidoreductases

NAD/NADP: Dehydrogenases

ATP/ADP: Kinases, ATPases

How Cofactors Affect Crystallization

Without cofactor:

Binding pocket is "empty" and flexible

Conformational heterogeneity (multiple states)

Lower thermal stability (Tm drops 5-15°C)

Result: Won't crystallize

With cofactor:

Binding pocket occupied and rigid

Homogeneous conformation

Stabilized structure

Result: Crystals form

How to Diagnose

1. Predict cofactor requirements:

Check UniProt: Known cofactors for homologs

Literature: What cofactors do family members use?

Orbion: Predicts metal-binding sites, cofactor requirements

2. Thermal shift with cofactor:

Measure Tm without cofactor: 52°C

Measure Tm with Zn²⁺: 64°C (+12°C increase)

Conclusion: Zinc is required for stability

3. Activity assays:

If enzyme, measure activity ± cofactor

If no activity without cofactor → it's essential

Case Study: Kinase Crystallization

Target: Novel kinase, full-length

Attempt 1: Apo kinase (no ligands)

Purification: Monodisperse

Tm: 48°C (low)

Crystallization: No crystals (6 months, 2,000 conditions)

Attempt 2: Kinase + Mg²⁺ + ATP analog (AMP-PNP)

Add 5 mM MgCl₂ and 2 mM AMP-PNP during purification

Tm: 58°C (+10°C)

Crystallization: Crystals in 3 weeks

Diffraction: 2.4 Å resolution

Lesson: Many enzymes absolutely require cofactors/ligands for crystallization.

Understanding Your Failure Mode: Quick Diagnostic

Before you set up 2,000 more crystallization conditions, determine which failure mode you're facing:

Symptom | Likely Failure Mode | Quick Test |

|---|---|---|

AlphaFold has long orange/red regions | Flexibility | Check pLDDT plot |

High % of surface Lys/Glu/Arg | Surface entropy | Calculate surface composition |

SDS-PAGE shows smear (not band) | PTM heterogeneity | Mass spec |

SEC-MALS shows multiple peaks | Oligomeric heterogeneity | AUC or native PAGE |

Construct includes disordered termini | Wrong boundaries | Compare to homolog structures |

Aggregates at >5 mg/mL | Aggregation | DLS at multiple concentrations |

Low Tm (<50°C) | Missing cofactors | Thermal shift ± cofactors |

Key Takeaway

Crystallization failure isn't random bad luck. It's a predictable engineering problem with known failure modes:

Flexibility (35%): Disordered regions prevent packing

Surface entropy (25%): Flexible surface residues oppose crystallization

Heterogeneity (20%): PTMs, conformational states, oligomers

Wrong boundaries (15%): Too much or too little protein

Aggregation (20%): Concentration-dependent oligomerization

Missing cofactors (5%): Protein unstable without ligands

Understanding your failure mode is the first step to solving it.